Why Magnum Fotos Matters

WHY MAGNUM PHOTOS MATTERS

“If your pictures aren't good enough, you're not close enough.” — Robert Capa

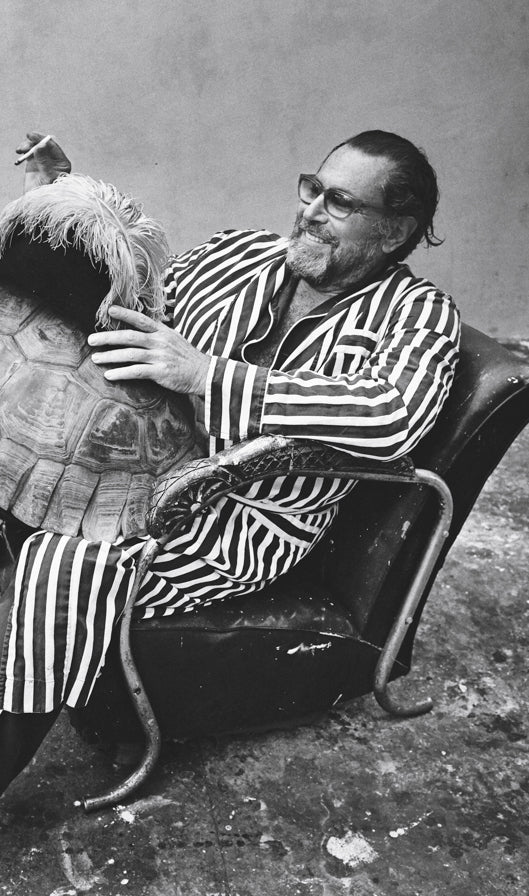

During the very worst hours of Hurricane Sandy, when it was unclear how much of New York was underwater but we knew that the Rockaways were ravaged, I got an angry phone call from an old friend and colleague, the decorated Magnum photographer Gilles Peress. I had known him for forty years as a cantankerous and fearless shooter, but he was older now, a considerably less strapping version of the rogue who’d made his name covering wars and their collateral damages. He was calling from the chaos of Breezy Point, livid that there was no one at the office who could help him send out his pictures. In fairness, Magnum’s New York headquarters were ringed by a small river and would remain without electricity for days. But again: He was in the field, doing what journalists are supposed to do. Why weren’t the rest of us doing the same?

The comic-philosopher Louis C.K. does a terrific riff on our use of the word starving, as if a few hours without food give us license to use a word that defines the daily miseries of millions. So it is, sad to say, with journalist, which we’ve apparently ceded to garbage crawlers and phone hackers and reporters who make up lists of people who suck at whatever profession they themselves never bothered to master.

The true journalists among us can be divined not just by searching for what they write or shoot, but for where it comes from; places inside themselves and in the world that most of us lack the stones to visit. I learned to distinguish between the real ones and the poseurs early on in my five-decade career in media. Between stints at college in the late- sixties, I landed a job as a messenger at the New York Times; by 1971, I’d worked my way up to what was generously called “news clerk” at the Times’s Week in Review section. Basically, I did whatever the editors told me to do.

My boss and mentor, a charming eccentric who wore double-knit shirts with paisley ties to lunches with world dignitaries, wanted me to be his photo researcher, a job I was less qualified for than most. Terrified by my own ignorance, I agreed to be the point person for every photographer who wanted a shot at working for the Times, which my peers considered tantamount to voluntarily reading every unsolicited, typo-laden manuscript sent in to the newspaper (a job, incidentally, that I’d previously held at the Times Magazine). In other words, was I nuts? I guess I saw a lot of truly bad portfolios, but I don’t remember any of those.

“These were people who were willing to risk everything.”

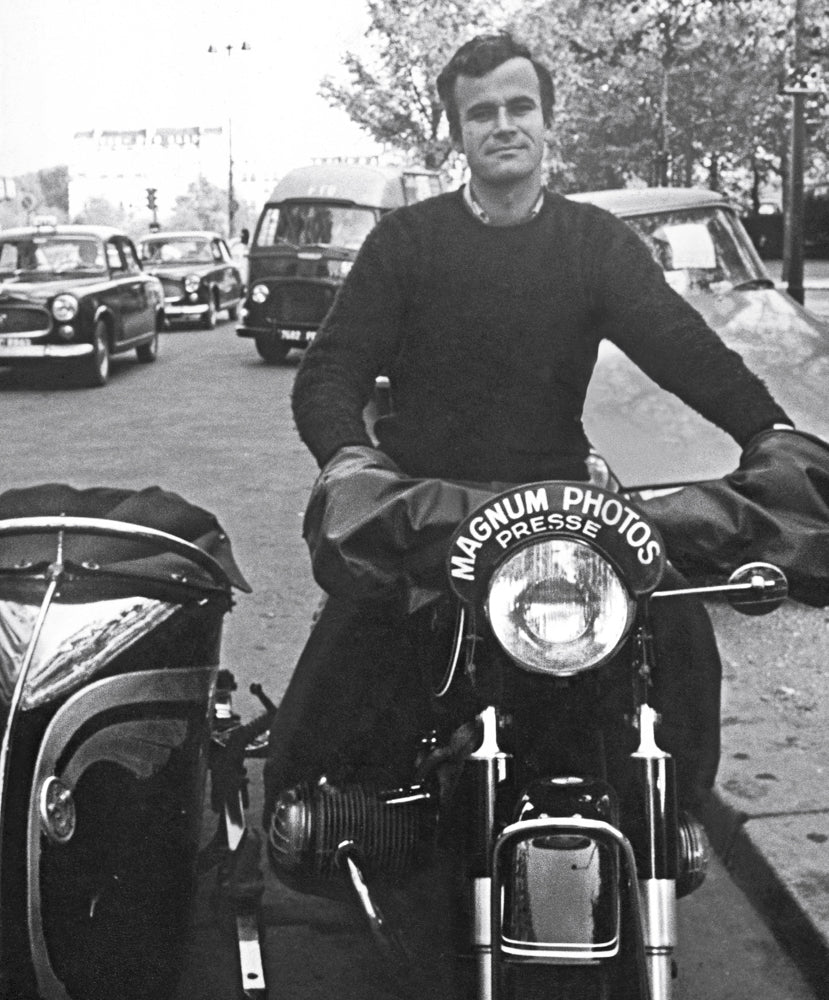

What I do remember is meeting a gang of young photographers who were all desperate to join something called Magnum, which I quickly learned was a legendary French photographers’ collective. The weight of its members’ talent was such that even the simplest request for a file photo would yield a pile of gorgeous images even a naif like me could recognize as exceptional; more nuanced, more artfully composed, more visceral.

But it was the young shooters — Gilles, Susan Meiselas, and Alex Webb, among others — who had me in awe. It wasn’t just their pictures that won me over. It was their willingness to go literally anywhere even the possibility of great pictures existed. I spent whatever paltry sums I could scratch together to finance some of their assignments, but they quickly outgrew my limited canvas at the paper. For one, their intellectual approach to photojournalism transcended the narrow definitions of news that governed most papers at the time. Magnum shooters went for the deeper story, and often the jugular, staying behind after the headlines faded to document the complexities of human struggle. Like all great journalism, and, not incidentally, great art, their photos challenged viewers to look harder, think deeper, get closer. They were provocative in the true meaning of the word.

“It wasn’t just their pictures that won me over. It was their willingness to go literally anywhere even the possibility of great pictures existed.”

Part of my job was to talk to correspondents and order up 800- word summaries of breaking stories, and it wasn’t long before I realized hotel suites and swank bars constituted the “front line” for most foreign correspondents. Not so for my friends at Magnum. There was a price on Susan’s head for the ten years she covered the Central American wars of the eighties. Gilles was in Northern Ireland on Bloody Sunday in 1972, and famously snapped a doomed partisan moments before his demise as he tried to crawl to safety. Alex’s pursuits were more esoteric, but no less risky; his seminal work in Haiti gave us a multidimensional study of a Job-like people in perpetual turmoil. These were people who were willing to risk everything to capture something human and true in the world and in themselves. I never had the guts to do that, and neither did most of the other journalists I knew.

Capa and his cofounders — Henri Cartier-Bresson, David “Chim” Seymour, and George Rodger — established Magnum in Paris in 1947 to fight for the rights to their images, which were routinely being stolen by magazines and newspapers before and during the Second World War. In doing so, they set a benchmark of excellence for combat photography that stood through the rest of the century and into the next. But even in the heyday of the great photo magazines like Life and Holiday, here and in Europe, art directors and editors who didn’t steal would still casually abuse their work, using crops and layouts that reduced complex images and stories to superficial symbols.

But bad crops were nothing compared to the indignities of the digital age. The proliferation of smartphones has reduced popular notions about photography to blurry selfies and citizen reporting. Print dried up, and with it the funding — there was never enough — that enabled the great storytelling that has always been Magnum’s hallmark.

And yet, the work continues. Bruce Gilden ambles onto any mean street he chooses, daring his subjects to say no. Larry Towell risks his hide in backcountry Afghanistan to document the landscape and deadly ordinance that’s taken so many young men’s lives. I would have recognized Peter van Agtmael as a fellow traveler if he’d walked into the Times back in ’71, and yet here he is now, putting his life on the line to follow in the Magnum tradition and bring his razor-sharp intellect to bear on our wars in the Middle East. When civil war broke out in Kiev, Jérôme Sessini was transmitting images from behind the barricades before the New York office even realized he was there.

“Its members are not simply journalists, but artists in the world, as the founders proposed; modern archeologists who excavate what’s buried beneath the surface.”

Magnum matters more than ever because there is so little institutional support for journalism of this breadth and ambition. With the death or diminishment of the great print institutions, we are left with the crowd-sourced confusion of Reddit and the gonzo adventurism of Vice. There are seeds of potential in both models, but there is grave danger in jamming complicated stories through untrained filters, particularly in a world where feckless freelancers wander into the jaws of ISIS. Magnum remains one of the few organizations with a tradition and a practice that sustains and furthers the foundations of serious inquiry. Its members are not simply journalists, but artists in the world, as the founders proposed; modern archeologists who excavate what’s buried beneath the surface and make it visible.

Susan Meiselas spends her time these days single-handedly running the underfunded Magnum Foundation, which aims to spread the gospel of Magnum by underwriting the work of worthy photographers around the world. Alex Webb is teaching and shooting whenever his overburdened shoulder permits. And Gilles Peress? He went ahead and published his own book on Sandy. The rest of us couldn’t keep up.