Pajamas & Palazzos

PAJAMAS & PALAZZOS

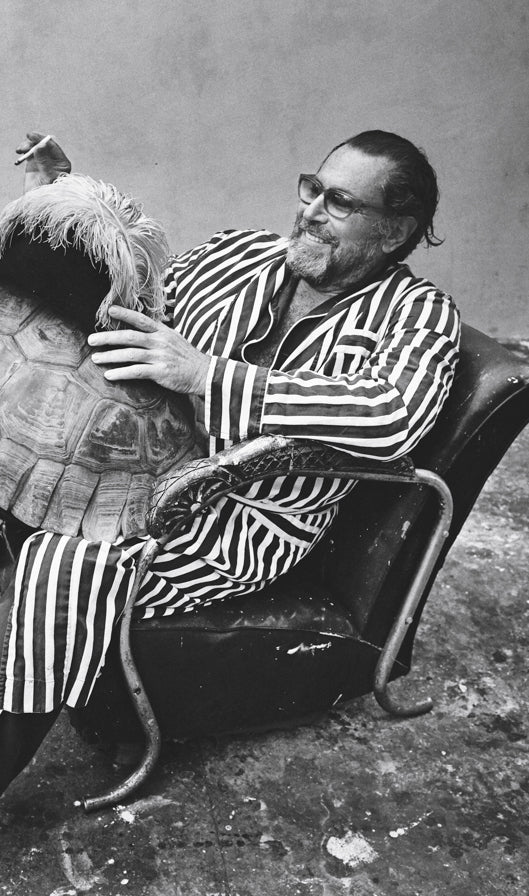

The artful adventures of Julian Schnabel

A doorman ushers me into the ground-floor studio of a tall, fuchsia-colored building on far West Eleventh Street, a transit point for outgoing art. Numerous large paintings lean languorously against the fourteen-foot-high walls inside the former stable, including several apparently based on GPS screenshots. My first inclination is to hoist one of these beauties on my back and haul it away like some thieving ragazzo in a Pasolini movie, but Julian Schnabel arrives just in time, stifling any larcenous impulses. Looking sharp in freshly pressed pajamas, the artist proceeds to guide me through the vast cabinet of curiosities inside his sprawling pink palazzo on the Hudson.

Schnabel’s studio and private quarters occupy the lower six floors of the twelve-story edifice, whose vertical additions briefly enraged the Jane Jacobean West Villagers amongst whom the artist planted himself some twenty-odd years ago. Today, Palazzo Chupi is a welcome visual respite from the rows of glass terrariums that have sprung up since along the riverfront. Building Chupi was a gargantuan project in line with Schnabel’s propensity toward the monumental. At one point he even thought he might “lose the ranch,” as he puts it, but his real-estate gamble turned out well in the end, to the chagrin of those who, critical of his art, his attitude, or both, wanted to see him fail. The whinging herd seems to have thinned a bit of late, particularly after the New York Times’ erudite bluestocking Roberta Smith wrote a lavish review of Schnabel’s April 2014 exhibition at Gagosian in New York, suggesting he is “both ahead of his time and in step with it, skillfully coaxing out the inner paintings in all sorts of ready-made surfaces.”

“Palazzo Chupi was a gargantuan project in line with Schnabel’s propensity toward the monumental. At one point he even thought he might ‘lose the ranch.’ ”

The reassessment of Schnabel’s work that Smith predicted is already in motion, with a vigorous series of international exhibitions stretching into next year. Although these late-breaking pronouncements please the artist, he has always blazed his own trail through the thorn-studded thickets of the art world, where critical assaults are often tinged with personal animosity and grumbling resentment at the lifestyle of the artist as well as his art. Needless to say, a life as capacious as Schnabel’s is bound to ignite a touch of envy in even the mildest of men.

Music is drifting through one of the rooms on the second floor. Assuming it is emanating from hidden speakers, I am quietly astounded when we enter the adjoining salon and discover a beautiful woman playing the violin, sheet music scattered around her feet like cherry blossoms.

“This is Tatiana, she comes down here to practice sometimes,” says Schnabel, by way of explanation. In the music room, along with the ravishing violinist, stands an eight-foot-tall stuffed grizzly bear, a Bösendorfer piano made of plywood (actually a sculpture by Tom Sachs, its innards packed with stadium-size Marshall amps), and a suite of works by Schnabel depicting a naked female tennis player, each ink-jetted image splashed by a gushing arc of white.

Entering another room, we are greeted by his Goat paintings, which adorn a wall across from a monumental Big Girl painting, from a series of portraits Schnabel began in 2001. Where to look next? Perhaps at one of the large paintings of a goat wearing a rabbit as a hat and an expensive-looking scarf. Cy, one of Schnabel’s twin sons with the designer Olatz López Garmendia, wrote a poetic critique of this work: “The garments on the goat, the scarf, the bead necklace, they’re familiar, why? He was wearing them. This is him in a past life. Where does it come from, a dream or a similar experience, who knows? […] His emotions in his present life intertwine with his past life as a goat years before he was born. He’s in love, he wants to pollute the sky with purple, so many clouds. And then pink dots; the sunset’s reflection on time itself.”

“This one I just made as if the goat was standing on top of a mountain — only the sky and the water and the goat — and there were no soldiers anymore,” Schnabel says, as we scrutinize the canvas. “If the one with the soldiers seemed apocalyptic, this one seemed more celestial. More like a portrait of God as a goat."

“When I was younger I thought I wanted people to understand me. As I get older I don’t think that’s part of the deal any longer.”

The Big Girl series sprang from Schnabel’s imagination at his outdoor studio in Montauk, where he has spent part of every summer painting since 1987. Their point of origin was a thrift-shop portrait he picked up of a girl whose eyes the artist had obliterated with a brushstroke and left to gather meaning over the years. His work is highly dependent on the elements. Chance encounters with salt water, wind, rain, and sunlight all play a part in altering and enhancing his materials, be they tarpaulin, found photograph, boat sail, or circus-tent fragment. Things teeter on the edge of decay and are revived by a touch of paint, a splash of molten wax. One painting fell to the ground on a windy Atlantic day and came up encrusted with bits of wild grass and insects, which became part of the piece. Hard to imagine another plein air painter — say, William Merritt Chase a hundred years ago out in Shinnecock Hills — thinking beach sand improved his oils.

“I think that what I do is different from a lot of other artists in that I make things with my own hands,” he says. “Everything is kind of handmade. Something about its physical reality has to do directly with my physical presence.”

How his paintings begin: One day while sailing down the Nile, reading Steegmuller’s translations of Flaubert’s letters to his mother, written in the same location a hundred and fifty years before, Schnabel noticed the unusual triangular shape of the felucca’s sail, and decided it would make a perfect canvas. The boat was named Jane, and, as he tells it, this somehow brought to mind the singer Jane Birkin, or perhaps her recent duet with Serge Gainsbourg was playing on the skipper’s transistor radio, and if you believe that . . .

Anyway, he bought the sail from the astonished captain, and then bought several more from other equally bemused Egyptian seafarers, and got to work conjuring Jane Birkin. I ask if perhaps inscribing certain names on paintings is a form of magical invocation; a way of wooing heavenly creatures, not unlike the many who have figured into his private life. But then his phone rings.

Another inspired moment, when the artist really saw the material on which he needed immediately to paint, and snatched it out of the ether like Ms. Birkin’s holy name, occurred as he was driving along the coastal highway near Zihuatanejo and came across a broken-down truck. The driver had removed and folded the tarp that covered the materials he was hauling, and to the artist the ruined fabric resembled the hide of an elephant. He bought it with the seventy dollars he had in his pocket, took it to the beach, tied it between two palm trees, and made a painting on the faux pachydermous hide as it rippled in the sea breeze. The next day, he went back and bought more of the same tarps from other truck drivers, who were as surprised and happy as the Egyptian sailors had been to meet such a crazy American artist.

“Painting is something I feel compelled to do all the time. Hopefully, one painting gives birth to another and you keep producing new work.”

“I made three of them. One is called War, one is called Apathy, and one is called Consumption. What I do is I take things that have prior meanings and I commandeer the prior meanings for a new set of meanings. A critic did once say I could turn garbage into garbage.”

Aside from his extraordinary fecundity as a painter, Schnabel’s ventures into film have resulted in several Academy Award nominations, despite his eccentric choice of subject matter. Before Night Falls is the story of Reinaldo Arenas, a talented Cuban writer who escaped from the oppressive regime in Cuba only to eventually succumb to AIDS during New York’s plague years. Schnabel recalls, “I was talking to the great Cuban writer Guillermo Cabrera Infante, and I said, I don’t know what qualifies me as the right person to do this. I’m not Cuban and I’m not gay, but I really identify with this guy. He had an incredible sense of humor for such a tragic figure and I don’t know what gives me license, but I understand this character; I understand his dynamic.”

Schnabel also identified closely with the claustrophobic horror of the protagonist’s situation in The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, in which a young man, superbly portrayed by Mathieu Almaric, becomes trapped in his own body by a massive stroke, able to communicate only by blinking. As a director, Schnabel has an uncanny knack for enlisting the right collaborators. In his first directing effort, Basquiat, about another charismatic yet doomed figure, Schnabel managed to recruit luminaries like Dennis Hopper, David Bowie, and Gary Oldman to give the production some much-needed traction.

“They helped me because they liked my art,” says Schnabel, acknowledging again the luck the gift of painting has brought him. Recently, another magical interlude in his charmed life found him briefly collaborating with the great screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière, now eighty-three years old, who was, among many other things, Luis Buñuel’s writing partner on nineteen movies.

“As far as making movies, I get a lot of offers, but I don’t really know when I’ll make another one, whereas painting is something I feel compelled to do all the time. Hopefully, one painting gives birth to another and you keep producing new work. In my case, sometimes that new work has been a film. You know, when I was younger I thought I wanted people to understand me. As I get older I don’t think that’s part of the deal any longer. You get the privilege of making the stuff. You don’t necessarily get the privilege of understanding what you did.”