The World On Your Shoulders

THE WORLD ON YOUR SHOULDERS

“Born under another sky, placed in the middle of an always moving scene, himself driven by the irresistible torrent which sweeps along everything that surrounds him, the American has no time to tie himself to anything; he grows accustomed to naught but change, and concludes by viewing it as the natural state of man; he feels a need for it; even more, he loves it: for instability, instead of occurring to him in the form of disasters, seems to give birth to nothing around him but wonders.” ALEXIS DE TOCQUEVILLE

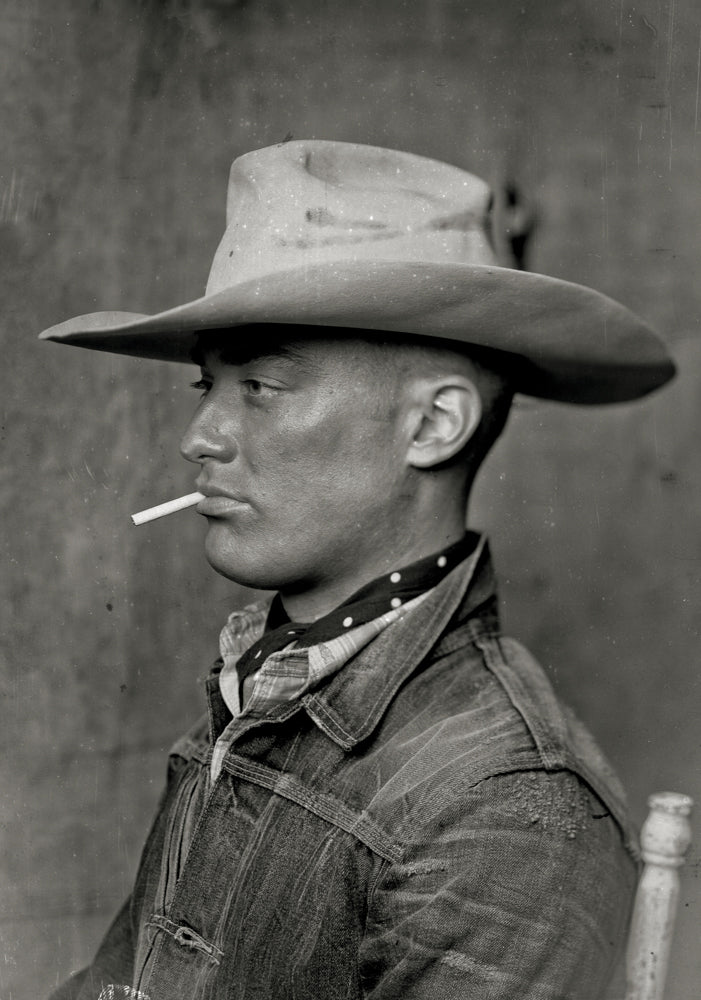

The first pioneers carried their supplies on horse drawn carts: yeast, flour and cornmeal, eggs, bacon, dried meat, rice, beans and a barrel of water. They made their clothes or repaired them on the fly. In big trunks they carried hammers, axes, ropes, nails and knives. When they trekked into forest too bosky for mustangs they carried a crucial stash of food and tools in a bag from which they fed their horses. It was called a haversack after the Low German word for “oat sack”.

The haversack was eventually sealed and painted black with linseed oil. A top flap and buckle were added to keep it closed. Inside, a separate pouch held rations. This design lasted through the Civil War, until en- gineers designed a brace with fasteners, attaching the bag to a uniform. The American Army’s haversack was made of leather, but that too was ditched for durable, lighter canvas. The bag was a small revolution. Compartmentalizing the interior and dedicating scabbards for utensils transformed the humble sack into a system. It no longer just held stuff; it made the carrier more efficient. But it still wasn’t a backpack.

Through the Spanish-American War the haversack remained an ancillary kitbag, fastened atop an external-frame duffle an infantryman strapped on his back to hump his shovel, bayonet, ammunition, change of clothes, blanket and the standard can of meat. Later developments in strategy redesigned his function. He needed to be maneuverable and integrated with his gear, mainly the Springfield ‘03 rifle, which found the haversack compatible with its cartridge belt. Soon a larger bag was introduced. A combination of capacious duffle and adaptable haversack, the internal frame M1910 was designed specifically for lighter, consolidated instruments. It was the first of our modern backpacks. The soldier emerged as a versatile system of training and tools.

March 1,1892. President Grant signed the Yellowstone Act into law, creating the world’s first national park. Sequoia came next, and then Yosemite followed by Wind Cave and Mesa Verde, Devil’s Tower, Petrified Forest and Rocky Mountain. Expanding westward, American pioneers discovered lands of such singular and uncommon beauty that written descriptions of them were sometimes mistaken for works of fiction. Preserving these landscapes - not exclusively for royalty or the rich but for everyone - was an idea as radical as the constitution. As America invented the National Park it manufactured a destination - “The Great Outdoors.”

A house is not a home. It’s a hole in the air filled with furniture and appliances. What make a home are those repositories of sentiment you’d gather into your arms and run from the fiery wreck of your sheetrock and shingle domicile. A backpack, similarly, is an assemblage of pockets and lining. Sentiment notwithstanding, the apothegms and forget-me-nots Sharpied across the fabric, a backpack is only as useful as what is inside – the iPad, the books, watercolors, a bottle of wine… a screwdriver and hammer. Inside a hiker’s backpack is not what he’d run from his burning house. It’s got what he needs heading into the fire.

The Ten Essentials are survival items recommended by hiking and climbing authorities for safe travel in the wilds. First listed in the 1930’s in Mountaineering: The Freedom of the Hills, they are a map, a compass, sunglasses and sunscreen, extra food, extra water, extra clothes, head- lamp or flashlight, first aid kit, fire starting materials, and a knife. The Ten Essentials are mostly self-explanatory. A flashlight? No shit. But a baton-style metal flashlight can tack in tent stakes, or pry loose rocks that have frosted to the ground when you need them for a fire-pit. Wind fishing line around it and you’ve got a reel. The Essentials are time tested, trial by fire items of versatility and size.

The military provided packs and essentials en mass. It also provided some key structural and sociological conditions that made “backpacking” — a catchall phrase for peripatetic yegs and bums, hikers and climbers alike — the popular activity it is. Not least of which is the national highway system.

Built to provide ground transport routes for troops and equipment, the national highway system also opened inaccessible territories to hikers and climbers from across the country. By 1920 more Americans lived in cities than in rural towns, a ratio that grew more lopsided as decades passed. But urban and suburbanites still looked homeward, over the horizon so to speak, to the forests and lakes and plains and mountains that, in their vast and silent peril, seemed to hold something essential the city and its sprawl didn’t have - more than easy safety and comfortable conveniences. Increasingly affordable automobiles followed highways through mountain ranges, across deserts and plains. Hiking and climbing organizations, like the Sierra Club and the Mountaineers, redoubled their ranks. And new grassroots environmentalist groups were continuously founded. The call of the wild was answered with a pair of boots and a well-stocked backpack. But trailblazers still relied heavily on military surplus.

1952, the space age is dawning. America has opened the most remote corridors of her frontier by railway and highways and turned great tracts of wilderness into parks. It is a decentralized, entrepreneurial culture strongly orientated toward technological solutions. Asher “Dick” Kelty is a carpenter, outdoorsman, member of the Sierra Club, and his shoulders hurt. He’s been hiking with fellow Sierra member Clay Sherman. They are tired. They have back pain. Their packs, military surplus, are constructs of heavy canvas on steal frames. Kelty gets an idea. If he can bring the weight on his shoulders down to his hips the stress on his upper body should dissipate.

He can travel further with less pain and fatigue. His first solution is to extend the lower portion of his pack’s frame and skid them into the back pockets of his jeans. It works, but there’s more to be done and he sets about building it. Kelty works from home making backpacks out of lightweight materials - nylon and aluminum. He keeps the shoulder straps and adds a hip-belt. The story goes that Kelty sold 24 backpacks for $24 a pop to his Sierra club friends. Five years later he was working full time out of an old garage along with his wife, who fitted and sewed the bags together. This was the final step to the modern backpack, creating a system of pockets and technology, zippers and solutions.

45 years into the Great Trigonometric Survey westerners caught their first glimpse of Mt. Everest. It took another 40 years before anyone realistically considered a summit of the mountain possible. It was yet another 7 decades until Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay achieved that summit. The math is worth considering. Over a century after its “discovery” by westerners, it took the cooperation of multiple European governments and dozens of expeditions before John Hunt’s assault on Everest in ’53. It took 400 people and 5 tons of baggage for two people to summit. Within 30 years – the first ascent on Everest without supplemental oxygen. Only two years after that, in1980, Reinhold Messner ascended solo. Over the next 20 years climbers made winter ascents, they descended by paraglider or by skiing. They set records for time, distance, age and gender.

“Expanding westward, American pioneers discovered lands of such singular and uncommon beauty that written descriptions of them were sometimes mistaken for works of fiction.”

Before there was essential tools, man was another animal on the plains, soft and pink, sometimes dreamy but often trembling in the middle of the food chain. According to Timothy Taylor, Professor of the Prehistory of Humanity at the University of Vienna, we are not the product of evolution the way chimps and gorillas are. Tools appropriated the role of environmental pressures, creating the dull fingernail, week jawed, and poorly sighted critters we are today. As we made tools, tools made us in a whiskey-throttle dash to the top of the food chain. There’s nowhere left to go. Why climb Everest? Because it’s there. And with tools in our strong, lightweight backpacks, we can. Everest is a natural conclusion to the telescopic nature of the convergence of man and tools. I’ve often wondered how the gazelle feels that outran the lion. Does it feel elation? Does the grass taste better, the air smell sweeter? Man has no more predators. The daily struggle to survive has diminished. We create a culture of challenges that have no godly purpose for being but to reaffirm our humanity.

George Mallory: “There is not the slightest prospect of any gain whatsoever. Oh, we may learn a little about the behavior of the human body at high altitude… But otherwise nothing will come of [climbing Everest]. It’s no use. So, if you cannot understand that there is something in man which responds to the challenge of this mountain and goes out to meet it, that the struggle is the struggle of life itself upward and forever upward, then you won’t see why we go. What we get from this adventure is sheer joy.”

After Kelty produced his first two-dozen bags manufacturers made lunatic grasps at new materials wherever they could find them. Chemical companies. Tire companies. Biologists! Who’s producing the lightest thermoplastic composites, the strongest polyamides? Craft a backpack, stick it on a climber and test that mother out. The backpacks you’ll find by the hundreds on mountains and trails the world over are made from the same super-lightweight, strong material as airbags. The frames are made from aircraft alloy. How’s this for telescopic: there have been over 5,000 ascents on Everest since 1953 – 77% of them happened after the change in millennia.

The1960’s counter culture became another demand source for the backpacking industry. With their dedication to self-expression and resistance to bourgeois materialism, the so-called Beatnicks and, later, the Hippie movement aspired to relieve themselves of possessions and join in a free spirited, free roaming community. The bare necessities were concentrated into a backpack. Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters exemplified the road trip as a confrontation with conformity in America.

Driving a carnivalesque bus called Further across the country while taking hallucinogenic drugs, they acted as advertisement and recruiters to the cause of social and political revolution. Protests were common, lasting days upon weeks. Backpacks were indispensable. The popular culture resisted the draft and opposed America’s involvement in Vietnam. Its core, activists from the civil rights movement, welcomed returning soldiers to their side, enlisting them to publicly recount and denounce the war. Naturally servicemen carried their possessions in standard issue haversacks and field packs. Well documented, leaders and followers, principal agents and figurants alike became the lasting kodacolor images of the time. Thus the backpack entered history as a symbol of both war and peace.

“As we made tools, tools made us in a whiskey-throttle dash to the top of the food chain. There’s nowhere left to go. Why climb Everest? Because it’s there. And with tools and a backpack, we can.”

As backpacking continued its crescendo through the1970’s a score of outfitters were introduced to the market. Many - North Face, Marmot, REI and Patagonia among others - were based on America’s West coast where the inscription of the frontier spirit hasn’t faded. More than a federation of serious outdoorsmen and women, the manufacturers also supplied the growing Wilderness Chic, a fashion movement that persists today.

More people than ever live in towns and cities, those hand-build Galapagos - man’s natural habitat. Backpacks are as varied and individualized as the people who wear them. But their purpose has not changed. It is a simple system, augmenting its wearer, making him more self-sufficient. With a backpack he can go further longer, do more, be prepared and in possession of the tools to survive in a wilderness with no trace of humanity. As Jim Whittaker, the first American to ascend Everest and K2 said, “If you stick your neck out, whether it’s by climbing mountains or speaking up for something you believe in, your odds of winning are at least fifty-fifty. If you take risks with preparation and care, you can increase those odds significantly.” (National Geographic, 2003). With a well-stocked backpack, the odds are in your favor. Excelsior.