RRL

RRL

To distill the world of RRL, Ralph Lauren’s assiduously vintage-inspired Americana clothing line, into a single object is a difficult and maybe even hopeless task. What do you go with? A beautifully aged leather saddle, that sturdy symbol of both the good life and the hard-working American West? A beaten-up pair of blue jeans — perhaps in a slim boot cut, the preferred style of Lauren himself?

Or maybe you try to boil RRL — “Double RL,” if you’re saying it out loud—down to a book. No ordinary volume, mind you, and certainly not a wordy one, but a weathered binder that’s titled The RRL Bible. There is only one such tome in existence; the fact that we at Man of the World were able to get our hands on it is an indication of the unprecedented access Lauren and his company granted the magazine for this story.

This “Bible” contains clothing labels — endless examples of them, geared towards purposeful men and done using a palette mostly comprised of red, white, and blue. “FIT WELL/BUILT WELL,” announces a sew-on tag. “BUY ‘EM BIG AND SHRINK ‘EM DOWN,” reads a staple-on label. Yellowed from age, stamped with a hodgepodge of ornamental typefaces, they are like ticket stubs from another world. Looking at them, you find yourself transported into the sort of dry-goods outpost a frontiersman of yore might have sauntered into for a new pair of dungarees — the kind of place, come to think of it, where the first jeans were sold.

As much as it resembles one, this book is no museum archive. Every label in there was created for RRL, “Est. 1993.” And yet, the Bible has about it the aura of some other time and place, one where fantasy meets reality and old meets new, and a desired but elusive way of life comes across as tantalizingly whole and concrete.

“RRL started with denim,” Lauren explains via e-mail. He had designed jeans before, of course. But RRL, Lauren explains, “gave them an entire world to live in.” Cowboy boots, washed chinos, biker jackets, buffalo plaids, a growing number of tailored pieces, the Navajo blankets that Lauren himself has been known to accumulate — they now populate that world, too, as do actual vintage pieces that blend into the RRL mise-en-scène the way sepia-toned archival footage might join with an authentic-looking period film.

Double RL is named after Lauren’s many-thou- sand-acre ranch in Colorado, and it seems fair to say that of all his brands this one is closest to what he owns and wears and to how he lives. “Lauren collects leather the way an anthropologist collects bones,” a writer visiting Lauren’s home in Westchester County once observed. No coincidence: collectible leather is everywhere at RRL.

“And it’s not a complete stretch to imagine 19th-century loggers, cowhands, or other wielders of pick and shovel attaining, or even striving for, an enviable sense of style. Didn’t Oscar Wilde once tell a gathering of Rocky Mountain miners that they were the best-dressed men in America?”

The label began, ahead of its time, as a different sort prestige pictures cannot linger on the ideals or textures quite like RRL does. This is a movie studio, you could say, whose head takes a special interest in wardrobe and set design and feels no obligation whatsoever to follow the familiar (if effective) contours of the three-act narrative. Watching this picture can be like watching those transporting early sequences of your favorite large-scale film on loop.

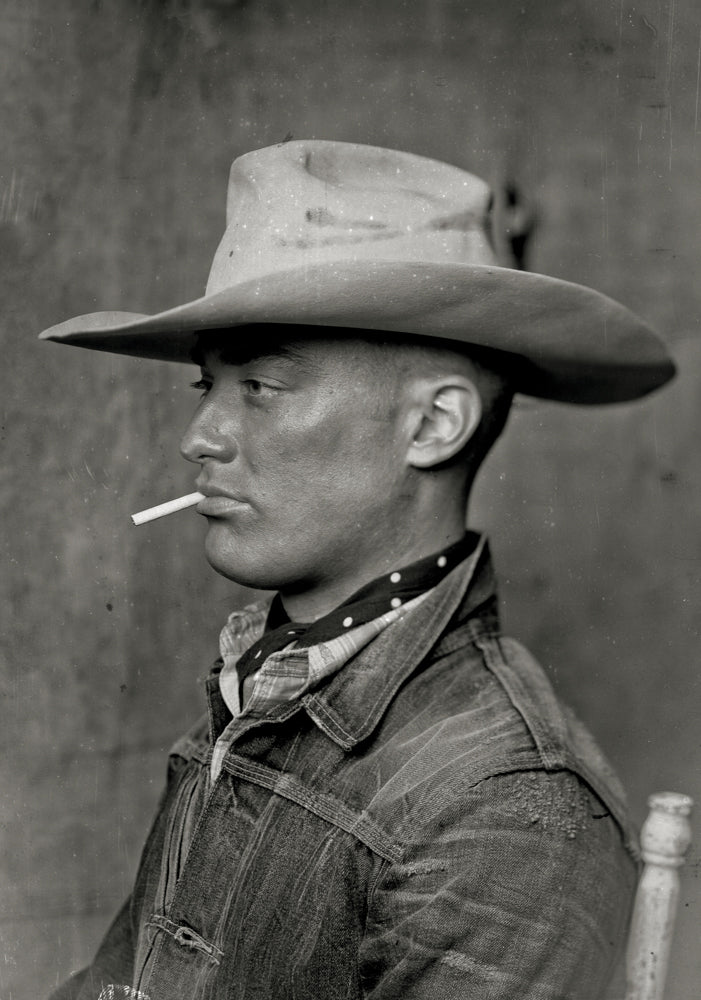

The historical past is relevant to RRL — each of those vintage points of reference belongs to a specific point in time. And it’s not a complete stretch to imagine 19th-century loggers, cowhands, or other wielders of pick and shovel attaining, or even striving for, an enviable sense of style. Didn’t Oscar Wilde once tell a gathering of Rocky Mountain miners that they were the best-dressed men in America?

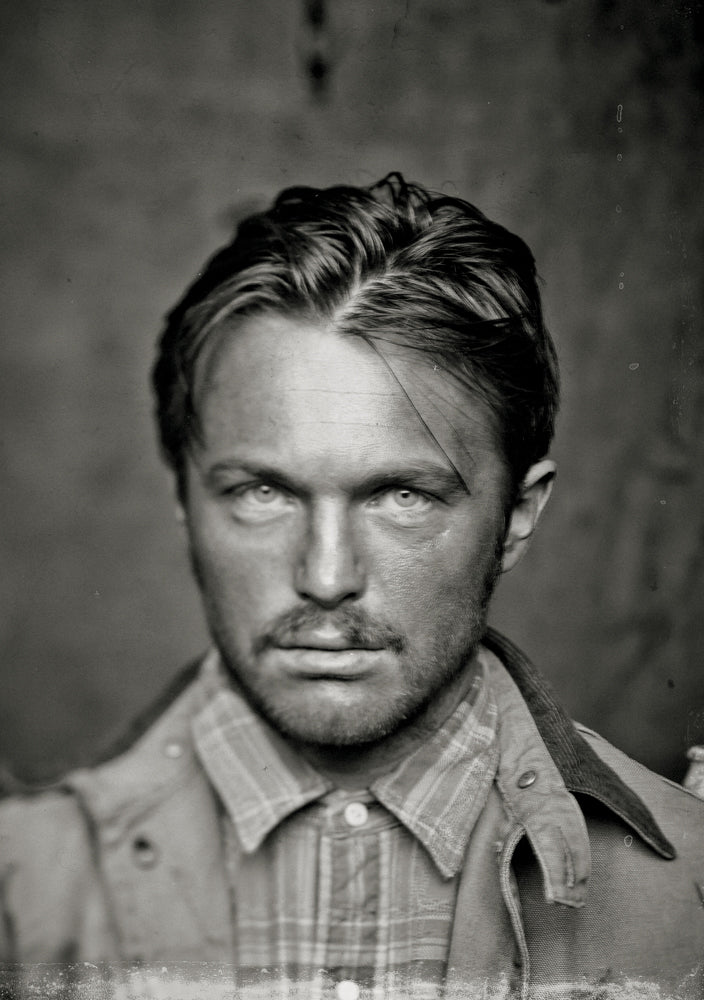

But RRL draws on mythology as much as history. This is a mostly, not to say entirely, American set of beliefs and traditions, examined and reinterpreted by a man whose own story belongs right in the middle of it. Lauren, who grew up in the Bronx, dropped out of college, and never studied design, has turned his childhood fantasies into an empire. He yearned for a more stylish, privileged life, reinvented himself, and achieved it. He now seems to have it all, including a longstanding wife and a trio of successful children. Asked not long ago where he’d most like to live, he replied, “I live in all my favorite places.”

Lauren told Oprah that as a boy, “I wanted to be everything, all at once.” An athlete, an actor, a dancer — even Batman. The appeal of the Western horseman has loomed large for him since 1982, when he bought the ranch, the stage whereupon he could truly start to learn the role. But it also preceded the ranch. “Even before that, I had a dream of the authentic life of the cowboy inspired at an early age by the movies,” Lauren says. Inseparable from that dream was, of course, the cowboy’s outfit. “The boots, the jeans, the jacket, the work shirt, the western shirt, the weathered hat are elements of his life and work. They grew out of a kind of utility heritage that I’ve always admired because it was real and romantic at the same time.”

Unlike the shuttered, Anglo-inflected golden realm that Lauren focused on with Polo, the world of RRL is stained with sweat and tobacco. It grows more directly out of American roots. We invented jeans, after all, not the leisure suit or the mesh polo shirt. RRL takes clothes we think we know and moves them up the ladder. Much time and money is spent on wearing them in, making instant the backstory that many of us (thanks in no small part to Mr. Lauren) now desire. He is not the only designer to finesse things this way, but he is quite possibly the most triumphant and most experienced.

If Ralph Lauren is a master illusionist, it is because he gets the details right. RRL jeans are spun on shuttle looms it was once assumed would never be used again. Cowboy boots come from a 150-year-old factory in Texas, using a last from the nineteen forties. (Footwear is one of the fastest-growing categories.) A pocket stitch, a reinforcement known as a felled seam — accents such as these are adapted from museum-quality originals, and you can bet that Lauren keeps warehouses full of them. It takes an RRL specialist about a day to wash a single pair of jeans, although the brand has evidently started moving away from all that washed denim and towards the stiff, indigo-dyed variety that your great-grandpa back on the farm would have wanted. Added proof that RRL is different: you won’t find most of these fits and fabrics in any of the other Ralph Lauren lines.

Another one of the big pushes recently has been in tailoring. One piece at the flagship that jumped out at me for its exceptionality was a washed pinstripe suit, made for a guy who’s the opposite of your typical city slicker — also, shirts and unlined ties in dulled, historic shades of pink and green (respectively) that you simply can’t find anywhere else.

“FOR WORKERS AND GENTLEMEN ALIKE,” goes the slogan for these dressier offerings. It’s a great phrase. To an extent, it’s rooted in sartorial tradition. As Lauren points out, “Even workers needed to put on their Sunday best from time to time.” Still, the crossover that’s being implied here is very much a contemporary notion. I don’t think it would have found much traction in the days when America was being built. Back then, blue-collared men might have aspired to the more obvious trappings of prosperity—but rarely, as is so often the case now, did lifestyle envy also flow the other way.

It isn’t enough to say that RRL is bringing back that which has been forgotten with a “modern twist,” as the hackneyed expression goes. It aligns our image of the past with that of the present, in a way that helps an individual envision his preferred future self. The story of the Double RL Ranch might even work as a parable here. Lauren, the story goes, was looking to buy property out West and failing to find what he wanted. Nothing lived up to his outsized expectations: the weathered homesteads were too small, and where were all those beautifully gaunt split-rail fences?

Finally, he settled on a rambling plot outside Telluride. It didn’t have everything, nor was it a blank canvas. There was a gorgeous, hundred-year-old barn. Lauren and his wife, Ricky, loved it; it was an original, and something to work with. Since then, it has become an identifiably Ralph Lauren property — not only that, but also an incubator of sorts for a pretty remarkable clothing line. The fences, one must assume, are precisely the way Lauren wants them, and I would suggest that these boundaries are deeply important.

Some would say that boundaries like these confine. They do, insofar as they keep the imagination from straying too far outward. But they also allow you to give deeper consideration to your own plot. And while I don’t mean to say that the boundaries at RRL are completely static, there is an acknowledgement there — one with which historians might be familiar — of limited raw material, one that lets the creative part of the enterprise plumb deeper. To spin out endless variations on something as simple as a clothing tag, say. And so maybe, if you had to distill RRL down to a single object, you’d got with an old split-rail fence.