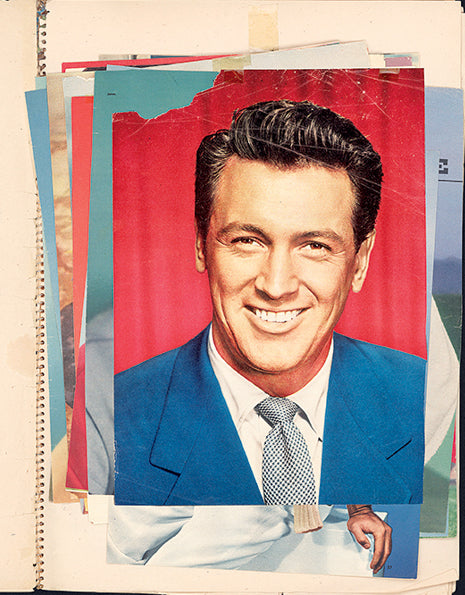

Luke Evans

LUKE EVANS

One of the first things you notice about Luke Evans is his voice. Before his introduction to an American audience he was a trained vocalist performing in productions at the West End, London’s Broadway. He’s British through and through, which can sometimes alienate an American, but Luke’s accent is warmer – maybe it’s the Welsh in him – it’s as disarming as recognizing a friend in a rough crowd. And he still manages to stand out as the bad ass in a pack of new films.

I met him once by chance. It was on the Lady May, a Yacht anchored off the coast of the south of France, in Cannes, where Luke was doing press. He’d just been cast as The Driver in No One Lives. Telling me about it that day on the ship he spoke lucidly of his psychopathic character, describing the synopsis in seemingly rehearsed prose that worked on me like a well-edited trailer. I couldn’t wait to see that movie. This was the sharp, undeniable presence of an actor. And the films have lately been piling up.

Since 2009 there’s hardly a role on Luke’s resume where he hasn’t played some chiseled Greek God (literally, sometimes) kicking people in the head and wielding lethal weapons. Physically, as well as in the martial arts, Evans has undertaken serious training, which is on full display in the character Owen Shaw, a deeply connected, former special-forces operator in Fast and Furious 6. Shaw has been hailed as the most dangerous villain in the series yet. That’s saying a lot for a franchise in its sixth installment. When other sequels go limping beyond the trilogy, losing both creativity and direction, Fast is turning-out new fans and reinventing its vision while creating action sequences that go viral and make for the most talked about commercial of the Super Bowl.

Okay, he’s good looking, and yes, as you’ll notice, his voice is on the gravelly side of dulcet, but if there’s bad blood between your character and his – in The Immortals, in Fast 6, as The Bowman in The Hobbit, The Crow! – he’s the last person you’d want to hear if you’re interested in keeping your bones in healthy arrangement.

From the West End to movies’ lead men in a few quick years, Luke’s ability to play the roles of men doing bad things without coming across as a bad man is a large part of his appeal. In The Great Train Robbery, a BBC miniseries, Luke stars as Bruce Reynolds, a true life heist-man who, along with a gang of 14 other men, stopped a money train on its way to London, robbing it of 120 bags of cash. The take was $60 million in today’s money. While many of his accomplices got nabbed quickly, Reynolds went on the lam for years, living the highlife across continents.

In The Crow, Luke plays a man obsessed with the murder of his fiancée and he meticulously takes his revenge. The role is another test of his ability to play a violent role and still come across as likeable. The point man to reboot a franchise is a role Evans is well suited for. And then there’s Dracula.

There are two popular themes in Hollywood at the moment: Vampires and Luke Evans. It was just a matter of time until they got together.

For centuries vampires have been depicted as heedless killing machines. Across all cultures they’ve been the archetype for our deeply unconscious transgressions. It took Bram Stoker seven years researching Eastern European folklore, distilling specifically human qualities of evil, to reinvent the vampire genre when he created Dracula. But Universal’s new project “is not adapted from the book. This is the origin story.” It’s a story Bram never told.

Since the mid 70’s a new model for the vampire movie tells the story from an internal structure, creating an emotionally sentient character, someone an audience can identify with rather than revile or fear. The new vampire is vulnerable, tragic: they’re relatable, and often damn good-looking. Studios learned that ruttish plays better than repulsive. Still, this is Dracula we’re talking about, the aristocratic “Dead Un-Dead” beating grotesque wings in the dark; the original bloodsucker named after a Romanian prince who baked children and served them to their mothers and was so sadistically cruel he was posthumously nicknamed Vlad the Impaler. That leaves an impression.

“This is not Bram Stoker’s Dracula,” Mr. Evans insists. The story that newcomer director Gary Shore will tell is about a Prince. When a Sultan threatens the lives of his wife and child “he puts his soul on the line” to save them. Don’t go into this movie thinking he’s a bad guy, Evans warns earnestly over the phone from the set, an hour before he’s scheduled to shoot another project. The man is hard at work.

Audiences like someone to cheer for, someone broken but tenuously whole, looking for retribution for the injustice he’s endured and willing to go and get it. Maybe it’s an aptitude for that kind of acting that casting directors have seen, and often deliver, in the form of Luke. Maybe it comes from his background, the working class Welsh, which most of us recognize instantly but rarely have the chance to express. Audiences, maybe now especially, identify with an actor who’s had their fight in his life and can bring it to the surface of his character. When we see that righteous pique in action, watch the sledge of violent justice shatter the abuses that befall him, it is not so much that we forgive the necessary evils as laud them, revel in the revenge, and are grateful for it.

It’s anybody’s guess what conventions Hollywood will explore from season to season. But Luke Evans likely has a part.