Jack Pierson

JACK PIERSON

TWILIGHT

Pierson’s art encompasses several mediums, from drawing and painting to photography, sculpture, and theatrical tableaus. “Some people in the art world have the idea that doing a number of things makes you seem less ‘serious,’ but I always follow my instincts. If I have the impulse to do something I just do it. Working in different disciplines does not make an artist less ‘serious’.

You have to kick those doubts aside and go with what you feel is most compelling.” The courage of these convictions has given his career an unerringly insistent upward curve, not only because he has a canny, or perhaps uncanny, sense of artistic timing and direction, but because the work he produces is always instinctively in tune with the times, showing us what we need to see.

“Jack Pierson’s home base since 1982 has been New York, but he remains itinerant, feeding the wanderlust that permeates his work, spending time in the high California desert, as well as summers in Provincetown, and more recently around Europe.”

Like his Boston expat contemporaries, Nan Goldin, David Armstrong, and the late Mark Morrisroe, Pierson began by taking photographs of his friends, “trying to make them look cool.” After a period of ‘cultural anthropology’ in Miami, a random visit to LA presented him with a fresh and alien landscape, which he avidly documented. “I never wanted to take photographs that much in New York, it seemed like the territory had been so well covered, but LA presented an entirely new perspective. I walked around a lot, and for whatever reason the photographs I took made a lot of sense to me.” Sure of his direction, Pierson maxed out the $500 limit on his credit card to make a series of prints, fifty of them at $10 apiece. Back in New York, they all sold.

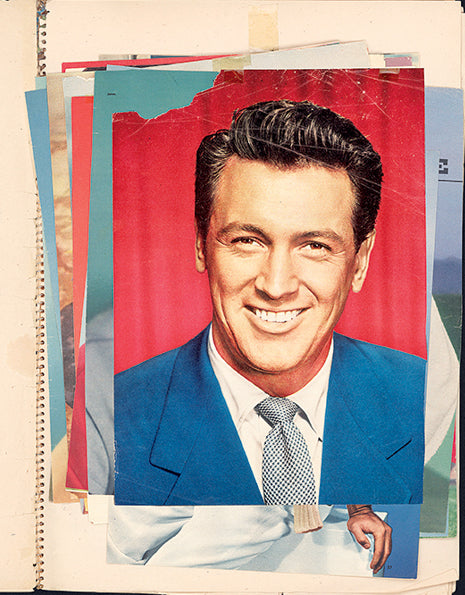

This tiny financial windfall resulting from the production of art made Pierson slightly giddy, and shortly afterwards another serendipitous moment occurred. He discovered on Houston Street a rag and bone man selling boxes of the detritus from the demolition of Times Square, then being converted from a street of sin into a kind of Disneyfied tourist attraction. The architectural junk for sale included the signage from many demolished storefronts, and as Jack gazed into a box of discarded steel and plastic letters he knew immediately that these objects with their implicit and explicit history could be transformed into something both personal and universal.

Money was still tight then for this self-described ‘hobo-hemian’, forty dollars went a long way. But Pierson figured he could double up on ramen noodles for a while. So he spent the grocery money and walked away with the bones of a concept, which he eventually executed with great success.

The single word “Stay” was his first piece, and like so many of the other words and phrases that followed, it resonates with all manner of emotive, sculptural, graphic and melancholic undertones. The words Pierson chose had personal and emotional weight, but he employed the colors, shapes and textures of the metal and plastic forms towards his unique sense of æsthetic effect. To complement these plaintive cris de cœur, he was creating handwritten drawings of whatever thoughts were passing through his head, or whatever was in front of him, as he whiled away the hours of this rather lonely period in his life.

“I found a personal narrative, with the drawings and the wall pieces. I would think about a broken romance or a deceitful lover and spew out my feelings. It was really ‘sketch book pages of a brokenhearted hipster’. I drew whatever was in front of me – an overflowing ashtray, dead flowers, or I might try to evoke the mood of whatever song was playing. It gave me something to do at night.”

Pierson now calls it research, but it was obviously a sad and lonely time. He also worked on his tableaus, a reconstruction of the rooms and bars in which he found himself. “I wanted things to be messy, it was in part a reaction to the very clean, neo-geo stuff that was popular at the time.” Pierson even slyly riffed on minimalism by using the corner of a room – in group shows nobody wants to be in the corner, but he embraced the corner, he just wanted to get in the room.

Much of his art kicks back, very gently for the most part, against some of the lavishness and financial expenditure that galleries demand. So when he started doing large-scale photographs, instead of spending thousands of dollars on frames, he simply folded the photographs to create a ‘sculptural’ crease, and then unfolded them and affixed them to the walls with straight pins, an art he had learned during a brief stint as an assistant window dresser. “Straight pins are genius, elegant, minimal, super functional. You never use pushpins. Pushpins have an association with offices, workplaces, a dull world. With straight pins you feel like Nabokov pinning butterflies, it’s more arcane, scientific.

So I went from beatnik to zen – suddenly there could be nothing in the object that wasn’t the object. That whole thing of framing and shipping, and then getting half the stuff sent back to clutter up your studio if it didn’t sell, it’s just not Bohemian! I wanted big portable photos so you could travel with them. Art to go! Naturally some people thought I couldn’t afford a frame. But they get a better patina when they’re free like that, they can breathe and live. Of course they didn’t sell that well, and some collectors would say, ‘Well it’s got this rip in it now, and pinholes, what shall I do? ‘You have to explain that’s part of the process.’”

Despite the persistence of his Bohemian veneer, Pierson lately has found himself doing three things he said he would never do – “make it big, make it shiny, and have somebody make it for you…” His recent show at Regen Projects in Los Angeles, accompanied by a brilliant movie-spoof press release that he wrote himself, had sixteen fourteen foot high monoliths filling the gallery, spelling out the ominous phrase, “The End of the World”. Pierson was understandably nervous about this move to monumentalism, this sly nod to artists who disrupt city traffic flow, and have the entire frontage of galleries dismantled to accommodate their massive artworks.

However, once the installation was underway, the artist began to revel in the Citizen Kane aspects of this massive crew working on his behalf, in watching the oversized words spell out his message. Shocked at first by the physical enormity of what he had produced, he realized after his initial qualms that all was good, Hollywood. Nothing had changed except his attitude toward the work. “After mocking monumentalism I was doing it myself, and loving it!” He will probably continue to work large, having just taken an enormous space in Ridgewood, a new art enclave three subway stops beyond Bushwick. Jack, as usual, is far out.