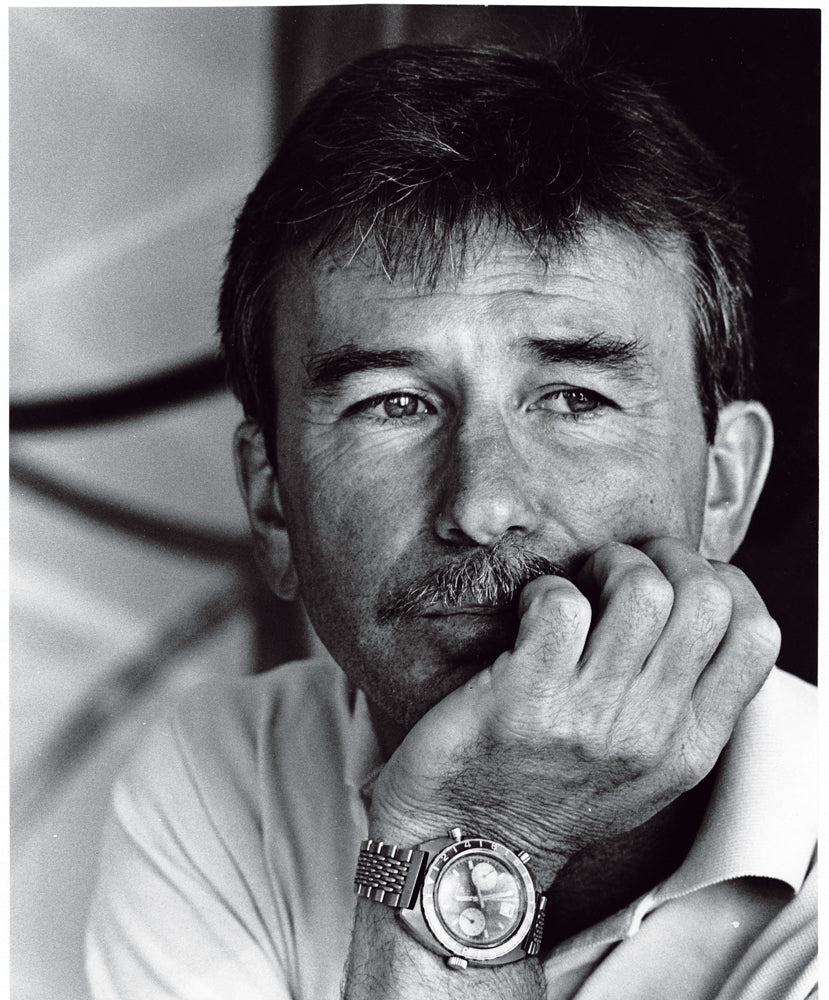

Billy Al Bengston

BILLY AL BENGSTON

Happy. Always trying to paint a picture as cute as a puppy.

Even though you drink decaf Billy Al Bengston will make you a cup of coffee. Within a mile of Bengston’s Venice digs — a multi-story labyrinth of color, art and the minutia daily life requires — are a multitude of caffeine choices. But if you really want to get a fine cup of joe the place to be is in the domicile of one Billy Al; who moved to Venice in the late 1950s; surfed when a board was thick and heavy and a drop-in could kill a man; took his spills on the pro-motorcycle circuit when, if a man borrowed a screw driver from you he’d track you down six months later to return it; and became a painter before there was bank in it.

“When I decided to be an artist everybody said, ‘you’re crazy, you can’t make a living being an artist’. And I said ‘making a living isn’t the idea,’” Bengston will tell you. And with this attitude, in 1968, Bengston earned a major retrospective at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. He was thirty-four.

HOME EC

“Growing up in a very frugal background was liberating. I was lucky. When I was in eighth grade in Kansas I took Home Economics,” says Bengston. “And I learned how to balance a checkbook and I learned how to cook, I learned how to sew, I learned about interest rates. I learned that you’re supposed to be able to live within your budget – I learned everything about that and it allowed me the freedom to do what I needed to do.”

The jobs that paid Bengston’s rent were simple. He built things. He did maintenance work. He cooked. He “gophered.” But he will dispel the notion that these are menial pursuits. He will note that running errands requires an ability to coordinate; to think things through. Cooking is timing and figuring out ingredients.

The thing about Bengston is that he breaks down and perfects the moving parts of everything he touches. He is probably the only man you will ever meet who explains that he ended his foray into bullfighting on account of his bad posture. And as the rest of the city buys their way into gluten-free, Bengston has ordered a tortilla press to make his own masa. Corn, the essential ingredient, was corrupted by the ethanol industry. The search for organic corn thus begins…

THE JOB

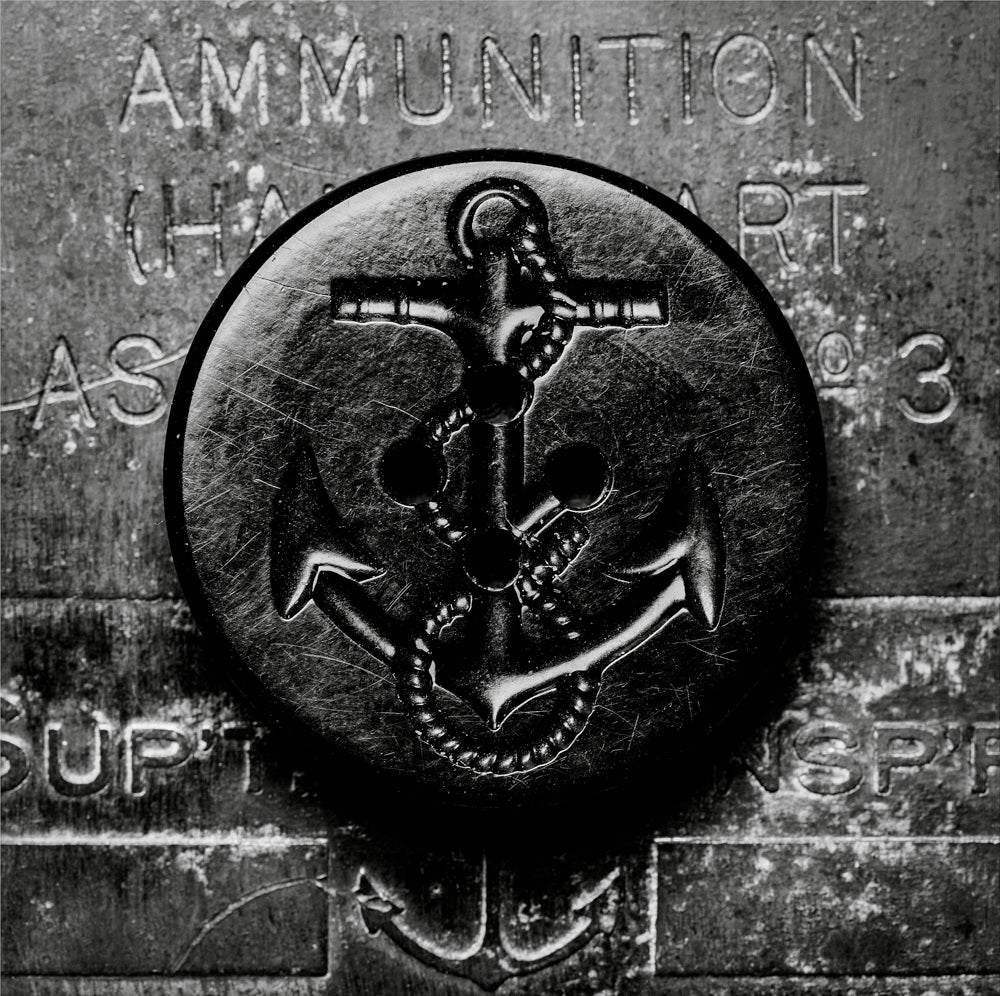

By the time Bengston moved to Venice he was a professional motorcycle racer. Work that involved hitting the oval on a bike without brakes.In regards to art, Bengston was frustrated by a few things; the lousy longevity of oil paint and what painting had previously incorporated — the portraits of realism, and the gestures of abstract expressionism — there had always been an element that a viewer could connect with. Bengston didn’t want to make a painting that was about something. He wanted: pure painting. What solved this riddle was within his grasp every time he broke down the mechanics of his bike; the industrial lacquers available in motorcycle or custom car shops, and aluminum, which he used as his canvas.“In the ’60s, I really felt that art had never been made. That’s when I started thinking about what art would be… Being an artist is like being a pure scientist. You’re solving problems that don’t exist,” he says as he begins to lay out a hypothetical inner conversation. “If you were a pure scientist what would your end result be? Don’t know… ”

“When I decided to be an artist — everybody said, ‘you’re crazy, you can’t make a living being an artist. And I said ‘making a living isn’t the idea’”

Bengston began painting pieces whose reflective surfaces cast off the colors that might be in a room. Though symbols were literally at the center of each work, they were not at the painting’s core. Instead, the piece changed depending on time of day and the viewer’s distance from it. He had left the territory of subject and entered the realm of pure paint.

“The biggest mistake I ever made was thinking that it had to have a signature… That’s when those sergeant stripes and all that stuff happened,” he says vis à vis a famous series of his work that featured the former. “I have no objection to it other than the fact that it was sort of arrogant hanging your hat on it when you’re thinking in terms of purer thought.”

HANGING…

Bengston tells you all this sequestered in one of two armchairs he de- signed, floating anonymously above a Venice street.

Two soliloquies, each painted after the passing of a close friend — artists Ken Price and Craig Kauffman — rest a few feet away. In one, a deep blue background is slightly dissected by a narrow vertical line that throbs, appearing and disappearing within the background. The second, hung away from the wall for the breeze to rotate it, features another vertical line, but shorter and crossed at the top by a rectangle — the colors, shapes and textures of the T revealed by a cut into the tactile paper that functions as the piece’s background. It’s as distilled as one could reduce a collage and still call it one — which Bengston doesn’t. “It’s a painting.”

If you ask Bengston about his process he’ll say that sometimes a piece that lurks in the edge of his peripheral vision in the studio pulls him into some mystery, or that an idea might wake him at night and he’ll say to himself, “okay if I remember this son of a bitch when I wake up, it’s good.” But before he crosses from the realm of Home Ec into that pure science, he will pass through the kitchen. It’ll be early. His wife Wendy won’t be up.

In 1958, Bengston purchased the first espresso machine Pasquini made available in Cali. Today, he’ll fire up a Cimbali, one of four java generators he owns, one of which is always packed, ready for travel. Billy Al Bengston makes his own coffee and it ain’t decaf.