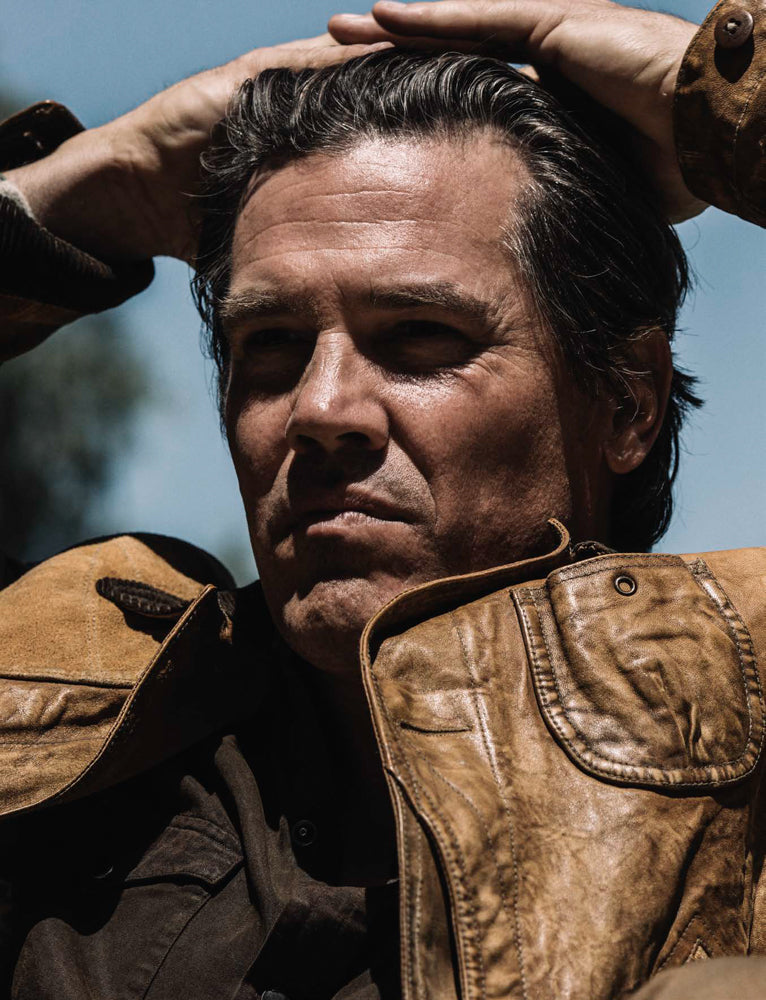

Wild Thing

WILD THING

Punk naturalist Walton Ford brings a fabled French monster to life

Walton Ford’s studio in downtown Manhattan calls to mind that Neil Young song “A Man Needs a Maid.” Its fabulous disarray stands in sharp contrast to the works in progress pinned up on the walls: exquisitely rendered watercolors of a man-eating beast that supposedly killed and ate two hundred defenseless shepherdesses in south-central France between 1764 and 1767. It’s the sort of story that appeals to Ford’s slightly sinister perspective on the natural world. The paintings are destined for an exhibition set to open this September under the auspices of the Paul Kasmin Gallery, at the Musée de la Chasse et la Nature in Paris. The timing couldn’t be better: this year, Ford’s paintings changed hands for record prices in the seven figures, as collectors like Leonardo DiCaprio and Tom Ford lined up to get first crack at his canvases. For those playing catch-up, a survey of his prodigious output can be found in a newly revamped version of his monumental 2009 monograph, Pancha Tantra, reissued this past June by Taschen.

Ironically, Ford did not grow up where the wild things are. “It wasn’t deep woods or anything — more like a golf course,” he says of his childhood in Westchester County, New York. “But I was constantly bringing home snakes and turtles and wild birds. I’d set up a trap in the backyard with a string and a stick and a peanut butter sandwich, and catch blue jays. I’d keep them for a day and then let them go.” After he drew them, of course. This catch-and-release method of nature study enabled Ford to make highly detailed and uncannily accurate drawings. He dreamed of becoming a natural history artist like James Audubon or Carl Akeley, depicting animals in their native habitats — “the puma sleeping on a flat rock, the lioness with her cubs, and so forth,” he says.

But moments of conflict and high drama began to creep into his work: a giant squid grabbing a scuba diver, a raging tyrannosaurus, “lots of battles, teeth, and claws,” he says. In fact, long before the prestigious Rhode Island School of Design accepted him, Ford realized there was a lot more he wanted to show than just the world as it was. After art school, he found his true subject by returning to the violent scenes of interspecies combat he had painted as a young boy — a subject which, to his credit, could not have been less fashionable at the time. “I really had a kind of revelation. I decided to do a knockoff of an Audubon painting, just for my own pleasure, because I could never afford one of my own,” he says. “I knew I could paint one, but I made it a fever dream of an Audubon, as if he had malaria or some other tropical disease.”

His new focus led him away from traditional representations of animals in nature and toward something gnarlier. “I’m making animals as they’ve appeared in human culture, as they’ve been vilified, celebrated, used as metaphors, kept as pets, and imprisoned in menageries,” he says. “I’m interested in animals that don’t choose to be domesticated but are forced in some way to have a relationship with human beings and what that does to the mind of the human, and to the mind of the animal. I always think about both points of view.”

Ancient myths, folklore, and old wives’ tales became grist for the mill. For instance, the 19th–century English explorer and naturalist Sir Richard Burton claimed to have given a dinner party for forty monkeys to record their secret “monkey language.” In The Sensorium (2003), Ford gave the apocryphal story his own twisted spin, depicting a drunken primate bacchanal, laden with callbacks to Burton’s memoirs. “I wanted to make the banquet capture the inside of Burton’s head and the way he looked at the world, how he imposed his worldview, and the way he perceived his monkeys,” he says.

Ford’s ten-foot-high Rhyndacus (2014), also reproduced in Pancha Tantra, is a particularly arresting image of a snake devouring a flock of songbirds. The mythical serpent comes from Aelian’s De Natura Animalium, an ancient Roman text that Ford, a voracious reader, discovered at a library and embellished. “I tend to think more like a writer than a painter in that sense,” he says.

The Beast paintings Ford created for the Musée de la Chasse took his practice into new territory. An eccentric repository of hunting-related art and artifacts, the museum is housed in a 17th–century mansion in the Marais district, its collection of ancient taxidermy, weapons, traps, and ephemera displayed alongside period and contemporary artworks in an ingenious curatorial mash-up. Ford’s new series depicts the Beast of Gévaudan, a werewolf-like creature that seized the imagination of pre-Revolutionary France.

“I’m interested in the animals that don’t choose to be domesticated but are forced in some way to have a relationship with human beings.”

In order to better integrate his pieces into the museum’s existing collection, he duplicated the basic composition of several of the paintings his works would be replacing. In place of a 19th–century portrait of two domestic cats fighting will hang Ford’s painting of the Beast chomping down on a wolf’s windpipe (see opposite page). The Beast of Gévaudan was “less a fable than a case of mass hysteria, fanned by the press,” he says. “If it was a folktale, it would carry an obvious moral lesson. In this case, people were just being torn apart by a mysterious animal — there wasn’t a hidden subtext.” So Ford invented one: “The Beast creates the anger in the peasant, which turns the peasant girl into the Beast, which then kills the aristocrat. To me it’s all about class struggle. The aristocrat is seducing the peasant girl, and then the beast is going to kill them both.”

Most locals at the time assumed it was common wolves attacking the young shepherdesses, until an overzealous Parisian newspaper reporter mentioned the word monster in his report. “It’s actually a perfect example of the way the mass media distracts the public from what’s really going on, which still happens today,” Ford says. “Your imagination can trick you into believing that there is a ten-foot-long animal living in the forest that didn’t evolve in a normal way and has never left a single footprint. I mean, it’s amazing how easily people can be convinced of things that are simply not possible. Even me.”