Tom Wolfe

TOM WOLFE

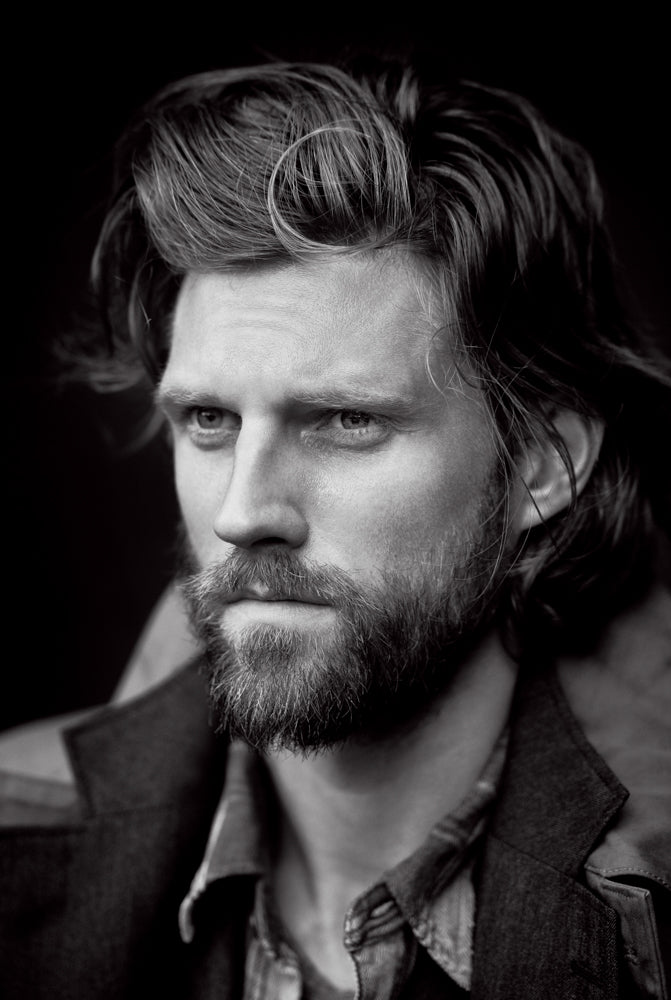

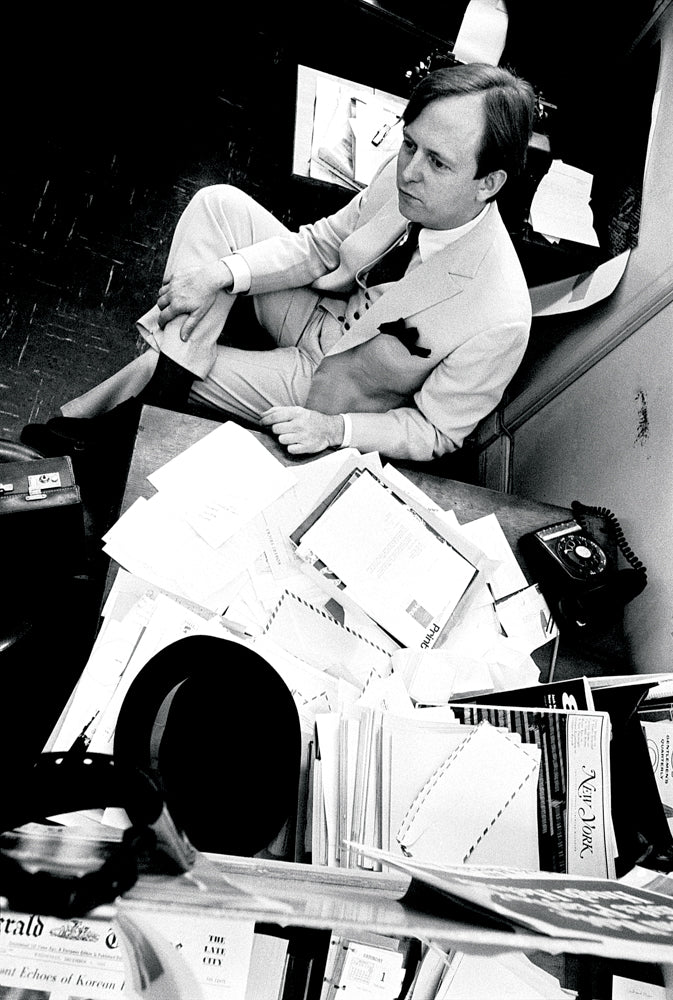

THE WRITE STUFF. At 82, Tom Wolfe still has it.

“A glorious place, a glorious age, I tell you! A very Neon renaissance – and the myths that actually touched you at that time – not Hercules, Orpheus, Ulysses and Aeneas – but Superman, Captain Marvel, and Batman.” Tom Wolfe

Hello, Tom. How are you?

I’m very well.

Thanks for talking to me.

I’m glad to do it! Man of the World, eh? I understand it’s a quarterly, correct?

It is indeed. One of those five-pound glossy jobs.

Well, you’re very brave. I was thinking about this subject the other day, in fact.

Which subject?

Guys with taste. Have you ever heard of Richard Merkin?

I have not.

Richard was the greatest dandy that I ever met in New York. He unfortunately died a couple years ago, but I think your magazine would have liked him. He never attracted, you know, major attention, or made the best-dressed list — there are no well-dressed men who aren’t also well known, apparently — but he was the real thing. He was a fascinating guy. He couldn’t stand the fact that Fred Astaire wore a carnation and a pocket hank. He said you have to choose one or the other.

Was he an artist?

He was a painter. If you’re interested in looking into the past, there is probably a lot of stuff on Google that I don’t know about. I have several of his pictures on my walls. They’re very funny because he painted in a two-dimensional abstract way using thick lines and large blocks of color. But he also included people, which never happened. Anyway, was just curious.

What else is on your walls?

Some of my favorite things I have on the wall are posters. They stopped making quality posters pretty much in the 30s. There were a few in the 40s, but then came television and other kinds of advertising. Some of it is just marvelous work. These were artists that needed to keep up the skill of drawing, which has died out now. You can’t expect any artist to be able to draw anymore, or use any conventional medium, really. Everything is standing on your head and taking your clothes off.

Speaking off lost art forms, we corresponded by mail several years ago and the letter you sent to me was handwritten in florid calligraphy — both sides, on a single sheet, with no mistakes. How and when did you learn to do that?

It’s really not taught anymore, it’s true. I learned it in my teens doing hand lettering for a commercial artist who was turning out occasional posts. In other words, if there was a play or some other performance coming to town, and he didn’t need to flood the world with printed posters, he would get a few duplicated and leave a spot for the specifics to be filled in by hand, by me. I don’t even remember how I got the job. Do you know what Speedball pens are?

I do.

Well, there was a thing called The Speedball Handbook that came with them that had all these different alphabets — Roman, Gothic, and so on — and I would sit down and copy them out. That’s what got me interested in the whole thing.

Were you an eccentric kid growing up?

I suppose I was in some ways. My greatest interest was in becoming a major league baseball player, and I ate my heart out for that. I played in high school, I played college, and I played two years of semi-pro ball, waiting to be discovered by scouts. I even played in a semipro league where there were a couple real hot prospects. There’s one I remember named Mel Roach — this was in Richmond, Virginia — and he was so good that you knew wherever he played there were going to be scouts around, so when I would pitch against him, I would really bare down. Much later on, I looked back at the box scores and realized he hit over 400 against me. I like to think that I sent him to the bigs!

It’s interesting you were such a jock… ?

When you’re in school the athlete is much admired, and the writer is… meh. Somebody says they’re a writer, who cares! But I was always really interested in writing and painting, too. During the Depression, the WPA [Work Projects Administration] used to have art classes in Richmond that I think were really just designed to give employment to the artists. It was 25 cents a session, and they were terrific. I was doing a lot of painting at that age and when I went to college, baseball practice and the art studio classes were at the same time. You can guess the one that I chose. I missed a great opportunity to really get familiar with painting.

You ended up doing a lot of drawing later on, though.

I did. I published a book called In Our Time that was mostly caricatures that I’d done for Harper’s magazine. I had a series in Harper’s with the same name for four years or so. I judge all drawings by how well the hands are done.

You do?

Oh, sure. Picasso actually invented Cubism for that reason. He quit art school when he was fifteen because he thought there was nothing more his teachers could teach him. Well, the next semester — the very next one! — they taught perspective and anatomy, and he couldn’t do either. He couldn’t do either one! Take a look at some of those early realistic paintings. He and Matisse always stuck the hands behind the back or on the lap so they didn’t have to paint them. Matisse wasn’t bad, but his hands were just awful. They looked like bunches of asparagus you’d buy at the grocery store! If I were Picasso, and I couldn’t draw or use perspective, I would have started a new movement, too. Take it from me: Picasso was a really, really bad artist, and Matisse wasn’t a whole lot better.

Which brings us to The Painted Word, your takedown of the contemporary art world, that was dismissed by a lot of people when is at was published, and is now required reading for anyone considering a career in the arts. Same goes for your book on modern architecture, From Bauhaus to Our House. How does it feel to be right all time?

Oh, it feels so good! [cackles] In all seriousness, I’m glad to hear that about The Painted Word. It’s not a critique, though. It’s a history. If you look at it, I never call any piece of art good or bad, though I certainly don’t take a lot of them very seriously. The same with From Bauhaus to Our House. It’s a history of taste. And do note that absolutely nothing changed because of either book! Now, more than ever, it’s all so terribly theory ridden. There’s a term at Yale in the art department called “de-skilled,” and the idea is that all this drawing and shaving and anatomy is false. It’s deceitful. I mean, how can you possibly pretend to have three dimensions on a piece of paper that’s only two dimensions? That’s the way they think. In fact, I’m looking at a catalogue right now of the Turner Prize winners and there’s nothing in there that you could do with your hands. There are people dressed up in certain ways, and there are objects in eccentric positions, but that’s it. I guess that’s art today.

Why do you think that is?

It all began in France in the 1880s. Writers, particularly poets, decided that people like Zola and Maupassant — probably the most popular writers in the world at that time — were totally passé. All this naturalism had to go. In their minds, the great artists in literature were Mallarmé, Rimbaud, and Baudelaire. They didn’t write for meaning, but for essences. Meaning just got in the way. Compared to what’s done today, they were actually pretty easy to read. And the message was basically: We don’t read what the masses read. We are part of an intellectual aristocracy, so we prefer Baudelaire.

This put a premium on understanding things that the mob — who, today, is known as the middle class — didn’t understand. Anything that was hard to understand, you embraced, because that put you on the side of the angels. It really does start right there, in France. It was only after the experience in France that people like Joyce and Proust began to be valued for either the difficulty of understanding them, or the boredom they induced.

I mean, Proust is extremely boring, but if you’re part of an aristocracy, you understand why that’s good. Joyce, to me, is like a wonderful book of wallpaper samples. He just tried everything! And some of it really works. Stream of consciousness is not bad at all, and he has parts on Ulysses in which people speak as if they’re in a play, and many, many other valuable samples, but it’s a terrible book if you’re trying to be entertained.

In The Me Decade you talked about the then emerging cult of narcissism. Did you ever think it would get this bad?

I associate the whole business of narcissism with the mid-seventies and eighties, but I never as a choice used the word narcissism, I was really talking about the pleasures that people got from putting themselves on stage, which was what all these new group therapies did. Each person would take a turn talking about his life and his personal feelings and it made them feel great. Everyone was listening to their problems!

And they hadn’t even invented Twitter yet!

Exactly. I mean if Marshall McLuhan were alive today, he’d be going crazy. He wouldn’t be able to keep up with it. I didn’t pay much attention to it at the time, I thought it was so foolish, but in the late 60s he said that television had changed the sensory balance of a whole generation of young people, and had turned them tribal. He pointed out that if you give a tribal person a piece of printed text they’ll just assume it’s a trick, but what they will believe is the next person who whispers in their ear. Ordinarily, we’d call that a rumor, but that’s what social media is. It’s whatever you feel like putting on there. It’s not all that hard to get a following if you can find the right topic.

Have you been following the Anthony Weiner scandal?

Oh yes, of course. I was reading about young Ms. Sydney Leathers just this morning. You know that old expression, you can’t make this stuff up?

Did you ever think you’d see the day? I mean, the stones on that guy…

You remember Nietzsche’s statement “God is dead”? Well, that’s really just based on the theory of evolution. He doesn’t mention Darwin by name, but says that the doctrine that there is no difference between man and animals is true, and deadly. He said that if people stopped believing in God — and it had to be God; you couldn’t just believe in a cause — it would lead to the eclipse of all values in the 21st century.

Bare in mind, he had already predicted the two world wars back in 1885, and one of them rather specifically. He said it would begin about 1904, and began in 1914, which is not that far off. Anyway, he said that the eclipse of all values is going to hit people much harder than war. It’s going to be devastating. And you can begin to see that happening in different ways. In the past, Weiner or anybody else wouldn’t have had to go nearly as far as he went in order to be considered reprehensible.

Is there still hope for American society?

You know, this country has it so good and nobody even stops very often to realize that. The wealth that is still here for common people is astounding. In India and places like that, when they see a video of the downtrodden in America they think it’s a practical joke! These people have television sets; sometimes they’ve got two cars! So I think we’ve got a long way to go, still. Also, this country is still very free compared to other countries, not just in moral matters, but also in what you can say about the government, the NSA’s domestic spying program notwithstanding.

How did you feel about that whole mess?

It’s a very pernicious thing. I don’t think Obama is going to allow anything bad to happen, but the next one may! It’s a terrible kind of threat. In the papers this morning I saw a court decision saying it was perfectly okay for the government to read peoples’ emails — not the content, but just to find out which way messages were flowing. Even that is more than I want to have to put up with.

You always took your work very seriously. Is it still the most important thing in your life?

In terms of a career, it certainly is. In fact, I’m pretty well under way with a new book about the story of the theory of evolution. It makes no difference to me whether it’s right or wrong; I just like the fuss it’s kicked up for the past 155 years. It’s become something close to a religion, but instead of being built upon things that you believe in, it’s built upon things that you don’t believe in, which confers superiority to you. There are so many funny things — so many serious things — that resulted from the theory of evolution.

On the silly side, to me, but not to the people that are suffering from it, is the current inquisition going on in academia. Any faculty member at any university of any standing who has actively opposed the theory of evolution is not there anymore. It’s really become quite amazing. People are losing their jobs over this. And some of the intelligent design people are scientists. They’re not stupid, and they’re in some drum-beating, right-wing Christian group in West Virginia. They’re real scientists. I take no position on whether they’re right or wrong, or anybody’s right or wrong, I’m just telling the story.

Do you write every day?

My process is the quota system, and I think that’s the only thing that works. If you fulfill your quota — mine’s about 1,300 words — then you can close the lunch pail and knock off for the day. Dickens used to write what he called “two slips.” They were pieces of paper about six inches wide and eleven inches tall. He had very tiny handwriting, and he could squeeze about 600 words on each side, and when he finished his daily slips that was it. Balzac was different.

Balzac just wrote and wrote and wrote and wrote. He went over any quota anybody ever had. He’d go out at night and then write until eight in the morning, fueled by coffee. By the end — meaning, when he dropped dead at 51 — he was drinking the Turkish stuff, which is really strong, as you know. But he got it done! He wrote 90 books of various types from 1832 to 1850. Can you even imagine? Best advertisement for caffeine I ever heard.