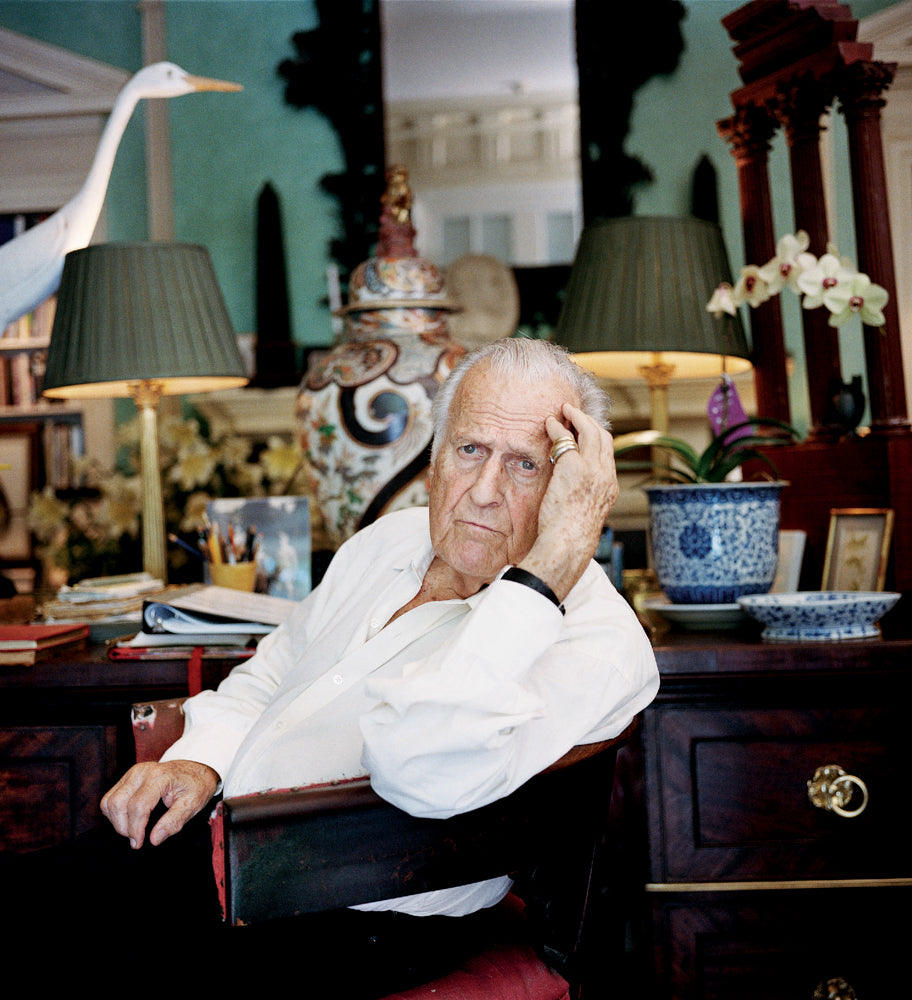

Sir John Richardson

SIR JOHN RICHARDSON

The Picasso expert discusses dining with the Windsors, the grand dames of cosmetics and the frescoes that got away.

HUGO GUINNESS: You’ve just had a huge success with your photography show at Gagosian Gallery, Picasso & the Camera. There were lines down the block. It was unlike any photo show I’ve ever seen. What

was your approach?

JOHN RICHARDSON: I knew I didn’t want walls plastered with

endless photographs of Picasso. I wanted to do a show that would reveal

how the camera played a role in his work. Photographic images were one

of his major sources of inspiration.

But what about the previous ones you’ve done of paintings by your old

friend Pablo?

Picasso had long since been dead when I embarked on these exhibitions.

The first one was a shocker: very late paintings that he did in his eighties and

nineties, before his death in 1973. The public had not taken to them — bullfighters and buccaneers in outrageous period getups, pawing big-busted fat-assed molls. Fans of early Picasso never warmed to them either, but the

new generation loved them. I hung the paintings informally, as if they were

the work of a new young artist. You could make up your own mind.

How did your recent show at Gagosian differ from your first New York

show fifty years ago?

The 1962 exhibit took place at nine separate New York galleries, with each

period of Picasso at a different one. It was a whole new concept which has

never been duplicated. People wandered from gallery to gallery, crossing

and recrossing 57th Street, 79th Street, and the areas in between. It was

heaven, but you certainly couldn’t begin to do anything like that these days.

The crowds and the traffic would make it impossible.

In those early days the art world was tiny, wasn’t it?

It wasn’t exactly tiny. There were a great many brilliant young artists, not least Warhol. But in those days the Museum of Modern Art called the shots and

there were far fewer modernist dealers. All this was about to change. The new stars were mostly American. That genius Leo Castelli set the pace in his celebrated gallery. Picasso’s late works were in keeping with Warhol’s — the freaks and celebrities and hookers of Andy’s world.

Is there any contemporary artist you’re interested in or whose work you’d like to buy?

I’d like to buy the ones I missed out on. I had a Rauschenberg, which I loved,

but I had to sell it because I was broke. I never had a Jasper Johns. I never had

an Ellsworth Kelly, except when he frescoed my basement. What happened

was, I bought two floors of a brownstone and when I got it, I gave a party

and we took the place apart. We tore down walls and we had a mass of wood

which we burnt in the fireplace and turned into charcoal. People did huge

sexy drawings on the wall. Great bacchanalias. And Ellsworth, who was an

unknown artist in those days, went down to the basement with some of the

junk — condiments, and things — left behind by the previous owner.

There was no paint, but there was Tabasco sauce, mustard, vinegar, Worcestershire sauce, as well as nail varnish and other cosmetics. So Ellsworth proceeded to decorate the walls. He did these beautiful still lifes of fruit — there’d be a mustard fruit bowl with some nail varnish oranges. We left it, but then we came down the next morning to photograph it, and everything had melted. The Tabasco and jam had dripped and there was nothing left but mess. So those were the only Ellsworth Kellys I ever owned. A pity we never photographed them.

Now, tell us about the social scene in New York in those days.

If you were in business — I was setting up Christies’ U.S. office at the time — it was obligatory to attend three or four cocktail parties every evening in pursuit

of clients. These parties became a terrible bore. Thank God they have gone

out of fashion, except for fund-raising or low-level social climbing. In those

days, forty or fifty years ago, women usually wore hats and they drank quite a

lot. I can still hear the cries of distress: “Oh, it’s Edna! She’s passed out again!”

One man would take the legs, another would take the arms, and they’d dump

her on the host’s bed with her squashed hat all askew.

“I had a Rauschenberg, which I loved, but I had to sell it because I was broke. I never had a Jasper Johns. I never had an Ellsworth Kelly, except when he frescoed my basement.”

Tell us about your great friend Patrick O’Higgins. Wasn’t he involved

in the same social world?

Ah, yes. Part Irish, part French, Patrick had arrived from London a few

years earlier than me, dressed in his glamorous Irish Guards uniform. I

had been warned against him when I was nine; as a result he became one of

my best friends. A star at all the cocktail parties I found so boring, Patrick

had become the right-hand man of [midcentury cosmetics magnate]

Helena Rubinstein. When we met by chance in the street, he invited me

back to his flat for a drink. On the floor was a valuable work by Juan Gris.

“What’s it doing there?” I asked him. “It’s a fake! Madame [as Rubinstein

was known to her staff] is convinced it’s worthless so she gave it to me.”

It was nothing of the sort. Instead of giving it away as a Christmas

present, as he was about to do, he let me sell it for him for a tidy sum.

And then what?

Patrick took me around to Madame’s apartment, where she proudly

showed off her modern art collection. Afterward, she opened a closet door

and said, “These are all fakes!” On the contrary, it was a valuable group

of large Gris black-chalk and pastel still lifes. I told her what they were

and arranged to sell them for her for a good price. As a result, Madame

always trusted me.

In his affectionate book about her, Madame: An Intimate Biography of

Helena Rubinstein (1971), he turned her into a wonderful figure of fun.

He adored her, and, as I recounted in my audio guide for the recent show devoted to her at the Jewish Museum, she didn’t realize it but she was an exceedingly comical person, and she and Patrick were a comical pair. He was heartbroken when she died, even more heartbroken when he discovered that her family had stuck her in a small back room in a society funeral parlor with one small vase of tacky flowers beside her. Patrick had

her dressed in her best Balenciaga dress and taken down to the lavish Judy

Garland suite, which he filled with her favorite lilies. One of Madame’s rivals

in the beauty business, Estée Lauder, also became a friend of mine. She was

much loved for her generosity, her hospitality, and her Austrian charm. Her

dinners were great fun, especially when things went awry.

An example, please.

I’ll never forget a dinner she gave for the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. The invitation took the form of a lacy Victorian valentine — beautiful, but

with Wallace Windsor’s title spelled “D-u-t-c-h-e-s-s.” We were formally

lined up to greet them. Everyone was bowing and trying to make wobbly

curtsies. Everyone except for a woman whose husband owned a fleet of taxis.

She held her hand out to be kissed by the Duke. I was close enough to hear

Wallace hiss, “The cheek of that bitch!” But Estée was a wonderful hostess;

the dinner was a dream except when the Duke insisted on speaking German

to the uncomprehending woman sitting beside him.

When someone asked why he was doing so, he replied, “Das ist meine Muttersprache!” His mother tongue. To the Duke’s delight a small band of German musicians materialized and started to play, whereupon he got up and had fun conducting them. His favorite song was about a little hotel. Most Brits were relieved he was no longer on the throne, but I found him somewhat tragic. Early one morning he called up to confirm a dinner invitation. I was in the shower, but a friend picked up the telephone and yelled, “Some joker claims to be the Duke of Windsor.” In a panic, I rushed from the shower. The Duke said, “Richardson, you should fire your man. We expect you for dinner at eight. We’re not dressing.” That must have been fifty years ago. Life is so much less personal, so much more public these days.