Shelf Lives

SHELF LIVES

“All a man needs is a garden and a library.” – Cicero

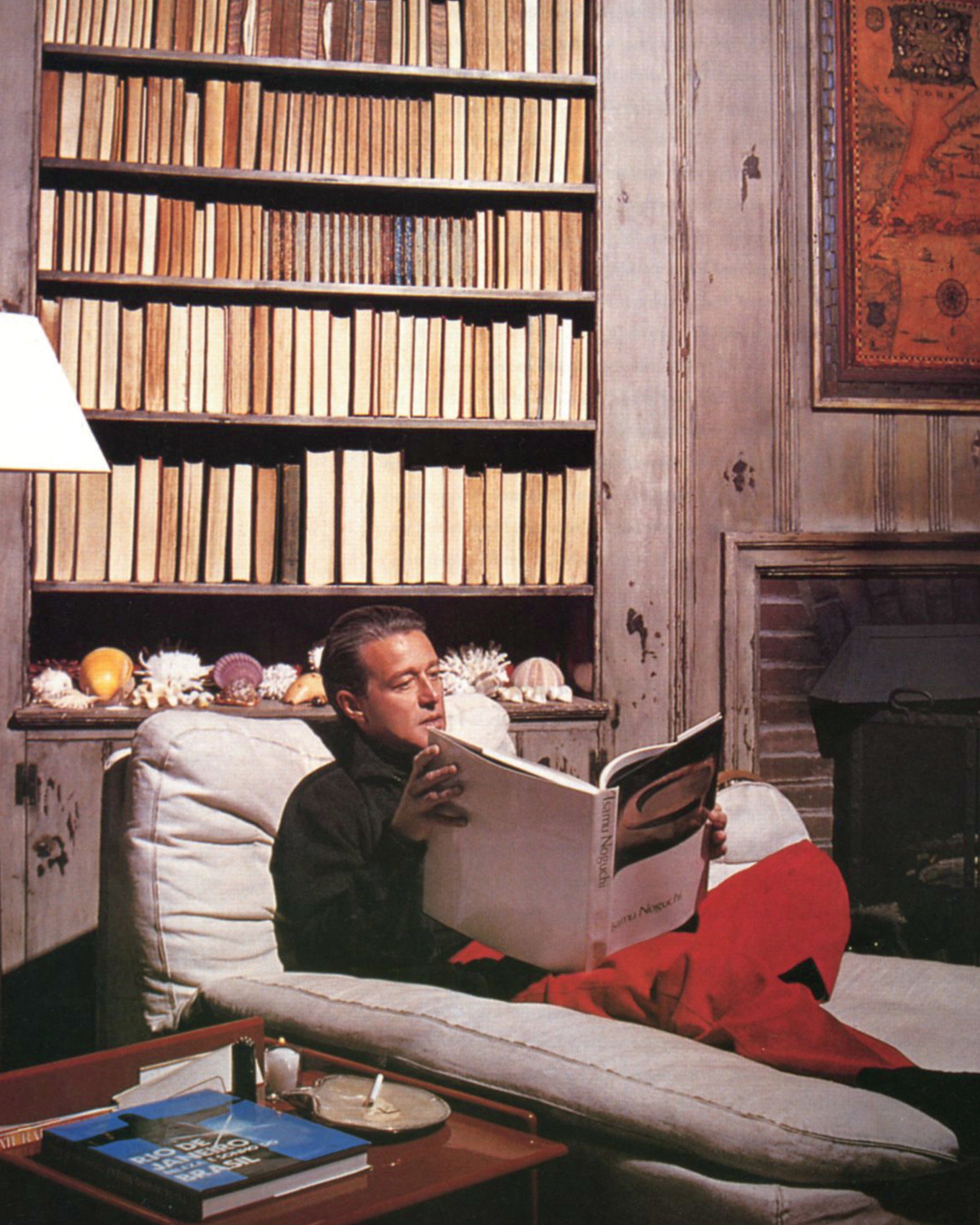

What is it about a bookcase, whether of hand-tooled mahogany or basic industrial steel, that triggers in so many of us an urge to browse, to weigh, to languidly fondle an attractive volume? Containers of magic and mystery, vessels loaded with crucial information, we treasure them in all their manifestations — Morocco bound or spindly paper-back — feeding on the nourishment they provide. Everyone should own a library of some description, a thousand volumes, or a single shelf. Each man’s library is a unique assemblage. In the Maison de Verre, in Paris, an eccentric and marvelous dwelling designed in 1932 for a cultured gynecologist by architect Pierre Chareau, the library’s leather bound volumes, in their high metal stand, are illuminated by that particular Parisian light falling through the opaque windows of the central salon. A dreamy refuge in which to read and ruminate as the world passes by, beyond the frosted glass walls.

Free to slowly absorb the words on the printed page, ensconced in leather club chair, or if you prefer, a monk-like seat in varnished and unyielding wood, surrounded by books precious for various reasons, their mere proximity exuding something close to spirituality. T.E. Lawrence, of “Arabia” fame, financed and built his ideal bookroom in a small Dorset cottage that he renovated very slowly over a period of years, a primitive dwelling he had originally acquired through the sale of a precious, golden dagger and his superb translation of Homer’s Odyssey. Lawrence valued his art and books far above such home comforts as a kitchen or a cooking stove. For many years the entire furnishings consisted of a bed, three chairs, a table and an ever-expanding library. Tragically, as renovations were nearing completion, this modest and heroic Englishman was flung from his motorbike and killed after swerving to avoid two schoolchildren larking on the country road.

Book-lined sanctuaries are reminiscent of fertile gardens. There is always weeding to be done, every so often one has to cull a few books from the collection, usually those unopened for a decade or more, to make space for new books, the way one might move a tired rhododendron for a new azalea. A madman’s folly really, this endless assembling and disassembling, reconfiguring of precious tomes. Books that have seemed essential for years might abruptly present themselves as surplus, to be taken down and donated to yard sales or charities, treasures for other gleaners to find, instantly replenishing their chameleonic collections.

These eccentric conglomerations of knowledge and art are imbued with humanity and civilization. It is painful when invaluable collections are destroyed — Pablo Neruda’s library in Santiago de Chile comes to mind, his exquisite objects looted and books burned in the poet’s garden by Pinochet’s thugs in the coup of 1973. Neruda died of heartbreak a few months after, and one can only hope that the perpetrators if not already there, will serve out a few centuries in some Dantean circle of hell.

“Everyone should own a library of some description, a thousand volumes, or a single shelf.”

People die naturally, of course, and their unique collections are often dismantled and sold once the relatives arrive. Books do not care — the ideas they contain are immortal, and they go on grouping and regrouping, augmenting other collections with their divine patina. Recently, 300 books from Henry Miller’s library were auctioned for the piffling sum of $2200, despite the priceless inscriptions and annotations on many of them. But Miller was a flaneur who embraced life, and doubtless would have cared less about this random dispersal. The legendary ‘anti-novelist’ David Markson, near the end of a frugal life in Greenwich Village, surrounded by books, arranged for his library to be scattered at random, after his demise, among the miles of shelves at his favorite bookstore, The Strand, in downtown Manhattan, which stipulation forced serious bibliophiles to grovel with common browsers among the dollar racks as they sought his nameplate.

I found my Markson quite by accident, while relocating current poetry rivals to higher shelves, well above any browser’s sightline. A slim volume of the poems of Tibullus seemed to jump from the dusty shelf. The inscription in Markson’s hand on the flyleaf confirmed for me once again the mystery and beauty of libraries and all that they contain.