Ring Of Fire

RING OF FIRE

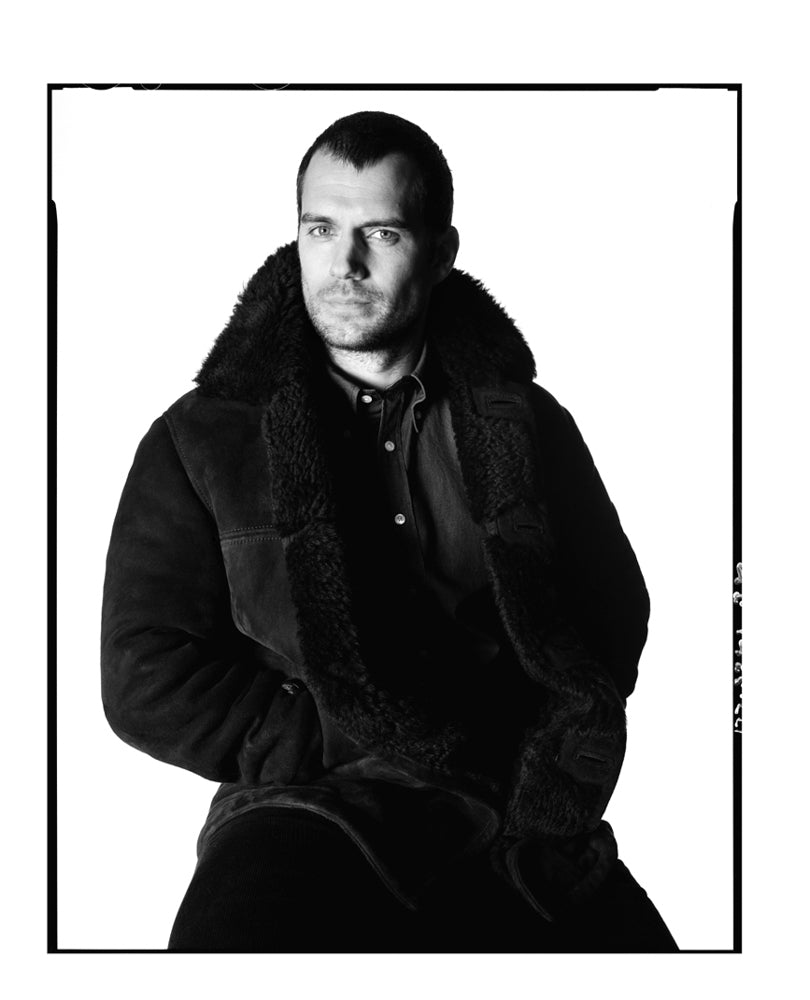

JOURNEYMAN ACTOR EDGAR RAMIREZ PUNCHES UP IN HANDS OF STONE

There’s an old cliché in Hollywood: Ask any handsome, in-demand actor where he makes his home and he’ll proudly tell you that he “lives out of a suitcase.”

Edgar Ramirez is no different, and he’s got the water-stained passport to prove it. Since storming Cannes in 2010 with a five-and-a-half-hour epic, Carlos — about the infamous political terrorist known as Carlos the Jackal — Ramirez has pinballed around the globe for his art, learning to surf in Tahiti with Laird Hamilton, hanging off a 3,200-foot-high waterfall in Venezuela, and feeding his sweet tooth in Thailand with Matthew McConaughey. “They have this crepe — it looks like a fake boob,” Ramirez says with a laugh. “Like a prosthetic little boob. That was a joke we had. It’s a flan made from sugar cane and coconut water. It’s delicious!”

How sweet it is. In the last decade, Ramirez, thirty-nine, has masterfully carved out a niche as Hollywood’s go-to guy for extreme intensity; he’s muscle-bound yet well-read, like a thinking man’s Gerard Butler. In Carlos, Ramirez played the Venezuelan terrorist from his early days as a playboy staring at his cock in the mirror until his balding, overweight denouement. It’s the kind of blood-on-the-celluloid role actors dream about, and it’s also a serious calling card. Man, did people call. Ramirez has since worked with Oscar nominees Liam Neeson and Ralph Fiennes — albeit in Wrath of the Titans. More notably, he tore shit up in Zero Dark Thirty (supposedly romancing Jessica Chastain off-screen), David O. Russell’s Joy, and last year’s fun (if entirely unnecessary) remake of Point Break.

But these were largely supporting roles or retreads. He’ll finally have the chance to deliver on the promise of Carlos with this month’s biopic Hands of Stone, about Panamanian boxer Roberto Duran — the five-time champion who shocked the world in 1980 when he abruptly quit a title fight with Sugar Ray Leonard, telling the referee: “No más.” The film, which co-stars Robert De Niro as Duran’s trainer, attempts to answer one of the great mysteries in sports history: Why’d he do it?

Duran started young, hitting the gym in his Panamanian slum when he was only eight years old. Ramirez tells me about his own childhood over a soy latte in Century City, Los Angeles. And while his youth was certainly more privileged than Duran’s, it was tough in its own way. Ramirez’s father was a military attaché and the family moved often — to Austria, Colombia, Peru, Mexico, Canada. Along the way, Ramirez picked up languages as well as bruises. Of childhood bullies, he says, “You’re always the new kid, the one with the accent, the one with the different culture....”

“Ewvery monthe had a bomb threat in my school,” Ramirez says of his childhood in Bogotá.”

When Ramirez was eight years old he was living in Bogotá, Colombia, in the middle of the Pablo Escobar drug war. “Every month we had a bomb threat in my school,” he says, “and they would get us to the gym. You’d miss the entire day just goofing around while the adults were worried about evacuating us from the school.” He wouldn’t trade it for anything. Ramirez wears his childhood like a badge of honor, while peppering his conversation with references to Alexander Calder, the Italian architect Gio Ponti, and how Caracas, Venezuela, was home to the first Dior boutique to open outside Paris.

In college in Venezuela, Ramirez trained as a journalist, working for his country’s answer to Rock the Vote, and his résumé shows in the way he listens. He’s dressed in a navy sweater and dark denim jeans with a healthy splash of cologne. And he pulls off a leather backpack as only a onetime telenovela star can. But what’s so gripping about him are his eyes. They’re as green as the Incredible Hulk and they probe your soul when Ramirez leans in, digesting every syllable. His English is perfect, too, lyrical even — and in searching for the right word, he has a habit of making the mundane sound poetic. It’s a skill he used to great effect in Joy, where he sweet-talked Jennifer Lawrence in a broom closet. It’s hard to imagine anyone else selling a blatant pickup line such as this one: “Maybe your dreams are on hold right now?” No más.

If journalism doesn’t seem like the best training, it’s actually informed his process: Ramirez researches his subjects endlessly. For Hands of Stone, he embedded himself in Panama for a year, building the character from the ground up in Duran’s own backyard, a ghetto called El Chorillo. Ramirez befriended Duran’s son Robin and started training on a terrace above a furniture store every day at noon, when the sun was most relentless. He lost twenty pounds. He fell on his ass. He got up. He focused on Duran’s footwork, the foundation of his power. “When you see a Panamanian boxer fight,” Ramirez says, “you could play salsa music against it and you’d see there’s a dance.” The transformation was so complete he even found himself telling bad jokes like Duran. At a party one night, Robin put his arm around Ramirez and dragged him away, saying: “Come here, Papa. You’re becoming too method.”

Ramirez felt the weight of this role immediately. It wasn’t just about doing justice to one man’s story but rather to an entire country’s identity. Duran rose to prominence at a time when Panamanian dictator Omar Torrijos was negotiating with Jimmy Carter to regain control of the canal. Sure, Hands of Stone is a biopic and the story of one of the most famous fights in history, but it’s set against the backdrop of a country asserting its independence. As for why Duran uttered those famous words, Ramirez hints at a much deeper story — about the birth of pay-per-view and the exploitation of athletes who weren’t just fighting for their country’s honor anymore. “What happened between these two guys is more interesting and more noble than someone getting cramps,” he says.

“When you see a Panamanian boxer fight, you could play salsa music against it,” Ramirez says.

Ramirez — who’s kept up his boxing regimen in the year since finishing the film — takes one last sip of his latte and wonders aloud whether he’s going home to Caracas soon or not. There’s that suitcase again. He’s just finished work on an adaptation of The Girl on the Train, opposite Emily Blunt. (For the record, he still hasn’t read the best-selling book. “I made the film,” he says, shrugging his shoulders.) Now he’s thinking about going to Tokyo with some friends, but he’s guessing a job will come up. It usually does. He isn’t sentimental, and travels with zero keepsakes to remind him of his apartment back in Caracas — the one with the terrace overlooking Mount Avila, and where exotic parrots sometimes fly by and say hello. His beloved country is in the midst of an economic implosion thanks to the cratering price of oil and rampant corruption. He sighs, and says: “That’s a whole different conversation.” If he misses anything about Caracas, he says, “I miss the light.”

Spending so much time on the road can get lonely. Perhaps he’d like to slow down, meet somebody. “I don’t know,” he says, “ask me in five years.” Then, in a way only Ramirez can get away with, he throws down some cheesy fortune-cookie wisdom and makes it sound like Shakespeare. “There’s a beautiful saying I read the other day, ‘The bird doesn’t belong to the nest where it’s born, but to the sky where he flies.’”