One Love

ONE LOVE

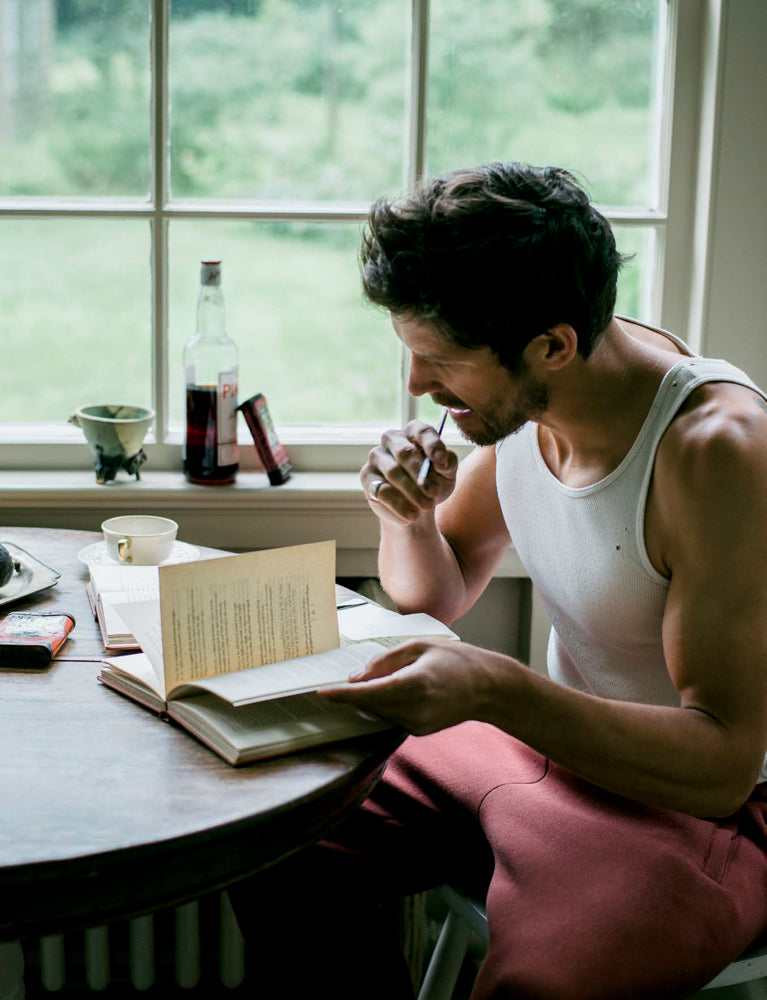

Island Records founder Chris Blackwell discovered Bob Marley and brought reggae to the masses. Then he really started jammin’

Chris Blackwell was born in London in 1937, but spent most of his childhood in Jamaica. At 22, he founded Island Records, taking the name from Alec Waugh’s novel, Island in the Sun, and changed the course of pop music, with acts like U2, Cat Stevens, Jimmy Cliff, and Toots and the Maytals. After selling the company to Polygram for a reported $300 million in 1989, Blackwell entered the hospitality business, assembling what is today known as the Island Outpost collection. It includes Strawberry Hill, nestled in the Blue Mountains above Kingston; The Caves, on the cliffs in Negril; and GoldenEye, the house built by Ian Fleming where he wrote all of his James Bond novels.

I read somewhere that in your early twenties you were close

friends with Miles Davis. How did you two meet?

I met him through Sid Shaw, a guy who had come down to

Jamaica to work with a great aunt of mine who wanted to be a singer. He wrote songs for Lena Horne and lots of people, and was at the center of the jazz scene. He introduced me to Miles, and when I came up to New York and saw him again, he

took a kind of liking to me. I never knew why, because he didn’t really

like white people in general, because white people had not been kind to

him. He was beaten up by cops outside Birdland one night, and was

always getting hassled. It was all very heady, looking back. I was going

to shows at Birdland all the time, and I didn’t need a ticket or anything.

Those types of things were my education. I was a huge failure at school.

How old were you when your parents sent you away?

The first time I went to boarding school I was eight. My parents sent me to a Catholic school in the Thames Valley in England called St. John’s Beaumont.

Aren’t you half-Jewish?

Yeah. My mother’s family were Jews by ethnicity, but not religion. They weren’t practicing at all. They converted to Anglicanism in the late

1800s after the rabbis merged the synagogues in Jamaica. The Sephardics always felt they were better than the Ashkenazi, so they all resigned.

And embraced Christ?

I suppose so. My mother, who’s 102, always says that she’s not of any

religion, but she follows the teachings of Christ — the original ones,

when he was still a hippie. I’m not a big one for religion. They’re all

businesses, you know. Later, they sent me to a school called Harrow,

which I loved. I had friends, finally. I was always sick with asthma as a

child, so there were never any other kids around. The only people I was

close with were the gardeners and people who worked in the house. All

the early photographs I have are pictures of me with staff. It’s bizarre.

How long did you stay at Harrow?

After I started wheeling and dealing, not long. I used to go to the town and buy liquor and cigarettes and sell them to the other students. At the

end of term by mistake I left the empty bottles and things in my room, and they found them. The housemaster said to my mother that he thought

“Christopher might be happy elsewhere.” That’s the English way of saying, Get lost! So I left school at seventeen and sort of drifted back down to Jamaica.

Did you get a job?

Eventually. One night, [playwright] Noël Coward, who lived near my

parents, invited my mother and me to a party at the Dorchester Hotel,

which was given by Mike Todd, who made Around the World in 80

Days, and Elizabeth Taylor. The governor of Jamaica — a wonderful man

named Sir Hugh Foot — was there and my mother knew him. He offered

me a job as his assistant aide-de-camp. If he hadn’t been transferred to

Cypress, I’d probably still be there. Instead I became an entrepreneur.

What sort of entrepreneur?

Jukeboxes. I owned and managed sixty-three of them, which put me in touch with the the music scene. I never really had any ambition to be anything in particular. I wasn’t driven. My life’s been sort of a series of happy accidents. I’m a big one for random — running into people, taking the

wrong way home and seeing something in a shop window you’ve never

seen before. The best example is probably the most successful person

whose success I've ever, in a way, had something to do with, and that’s

Richard Branson. We had an act on Island Records called Emerson, Lake

and Palmer, who were very successful. I hated them — I thought they were

just completely pompous. Anyhow, they wanted to start their own label,

and I thought that was just ridiculous. But they did it anyway, and they were having a party for the launch. I said, No way. I’m not going anywhere near that. But the guy running Island at the time for me said, “You’ve got

to go. It’s one of our biggest acts!” So I went.

At the party, I find myself talking to somebody — he came up to me, I think — and I’m thinking, This fucking guy is amazing. He's an absolute winner! He’s telling me he wants to start his own label and he wants to know if I’ll distribute it. I felt he was such a winner I said yes on the spot. Afterwards, I’m talking to my label guy and tell him all about this amazing kid I’ve just met and how we’re going to distribute his label, and he says, “We can’t do that, he’s in deep trouble. He just got caught bootlegging records.” What he’d done was, he’d driven his van over to Dover and pretended to put the records on the ferry to Europe to avoid paying tax, but then turned around and sold them in England. I said, “Well, my God, that’s not a crime!” So we did a deal with him, and the first ten years of Virgin were with Island. I’m a huge fan of his. He’s like a schoolboy. He’s shy at first, but then he’ll push people into pools and things.

When did you meet Bob Marley?

I actually released his first single [1963’s “Judge Not”], but I didn’t meet him then. I remember it because I misread the label on the box that the tapes

were sent to me in. I remember thinking, Robert Morley? The foppish

English actor? We ended up pressing five hundred or so with the wrong

name. I heard each one is now worth a thousand dollars or something.

When I met Bob properly a decade later, he was looking to have hits in the

American black music market, and I said, “It’s not going to happen,” which

made him kind of upset. I told him he shoulf be a black rocker.

He listened to me, and I worked with him a lot on Catch a Fire, adding elements that I knew would tickle the ears of my constituency, which was college kids who loved rock ‘n’ roll. I felt his music would really resonate with them. So I layered on guitars, put on synthesizers, and I thought, Right, this is a fucking great. I was really proud of it and remember being absolutely crushed when I learned it only sold eight thousand copies. By the end of the year it had sold fourteen thousand, which was still devastating, but by then I knew we were on to the right thing. The next year it broke through, but it was never on the radio. It was viral, for lack of a better word.

“If I had been there, I would probably have gotten shot, too.”

In 1989 you sold your stake in Island and started focusing on your other

interests. Why hotels?

I think it’s the same thing that drew me to music. I like turning

people on to stuff, and I love Jamaica and especially Jamaicans.

Can we talk for a second about the assassination attempt on Bob Marley

in December 1976?

We can indeed. I was supposed to be there. I was only not there because I’d gone to Lee [“Scratch”] Perry’s studio because I was releasing a lot of records with him. He’s the genius of geniuses in Jamaican music.

I went down there, and he played me this great track. It has a terrible

title — “Dreadlocks in Moonlight” — but I loved the track. I said, “What’s

this?” He said, “Oh, it’s a demo I’m doing for Bob.” And I said, “Bob

doesn’t need any songs. Why don’t you put it out yourself?

How long will it take to mix it?” And he said, “Maybe an hour,” and I said, “I'm not leaving the studio until you mix it.” Of course, it wasn’t an hour. It was probably about three-and-a-half. When I finally got to Bob’s house on Hope Road there was this wall of police. If I had been there, I would probably have gotten shot, too. It was a group of coked-up kids — paid gunmen from the JLP party. They fired sixty-five bullets! I brought Bob up to Strawberry Hill for a couple of days, then he did the Peace Concert as planned. He still had a bullet in his arm when he did the show.