Man = Animal

MAN = ANIMAL

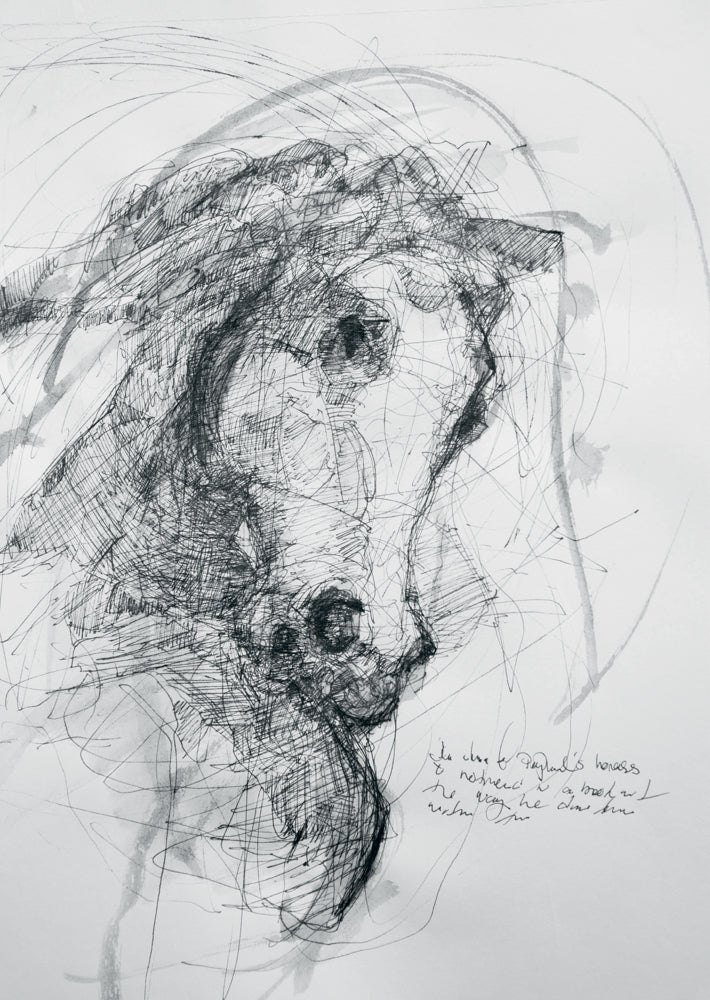

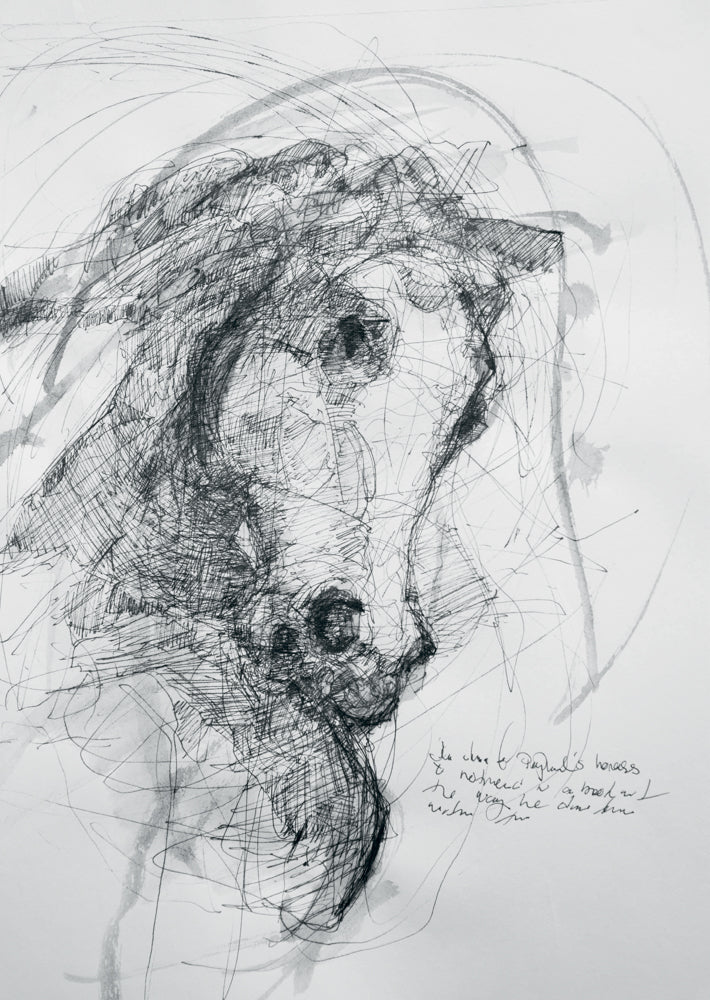

Nick Turner’s evocative delineations of the classic form of the horse are in the tradition of a long line of artists who managed to evoke the mysterious and noble qualities of the animal, a line that stretches from Susan Rothenberg, Joe Andoe, and George Stubbs to the unknown humanoids who decorated the walls of prehistoric caves.

Turner grew up around stables, living an itinerant life with his family in northern New England, where his bohemian parents homeschooled him, and where he came to know something of the solitary life. He now divides his time between New York City and his studio deep in the Maine woods, where he paints alone in an uninsulated barn through the winter, an act that would seem to verge on masochism. Smoke from a thousand woodstoves perfumes the air; someone is buying a quart of oil and a pint of vodka in the One-Stop at 8 a.m.; snow is falling; cows’ ears are snapping off in frozen meadows. Through the long winter nights that begin around 3 p.m., the only sounds you hear are tire chains churning the tarmac. This icy solitude suits a guy who sees man as animal, and defines nature as a state of war.

Clad in a survival suit, careful not to let his paint freeze, Turner engages with the solitude and the cold. He claims the extreme conditions connect him to the primeval the way riding a horse connects you not only to the Kentucky Derby, but also to battles and slaughter; to warriors descending on defenseless peasant villages to pillage and burn. His imagery fosters these antediluvian memories, backed by an imaginary soundtrack of Patti Smith raving about “horses, horses, coming in in all directions / white shining silver studs with their nose in flames...” Do ya know how to pony, Nick? Yes, Nick can pony. His exquisite renditions of the horse’s shapely contours, unchanged over thousands of years, conjure a creature far removed from the grinning banality of the famous Mister Ed, and one closer to the anthropomorphic, hyperintelligent Talking Horse who canters through Edward Dorn’s epic American poem, Gunslinger.

Turner has been studying the outlines of this elegant animal up close since he was a child exploring the nearby woods. Throatlatch, fetlock, pastern, and croup — he knows each animal’s parts by heart, and can tell you at a glance how many hands that mare stands. Turner’s fluid line in his ink and charcoal drawings contains hints and echoes of the animals drawn by the first hunter-gatherers on the cave walls of Europe 50,000 years ago, examining the pure synchronicity of man and beast, ancient connections to the first horse in its wildness, and then to those which moved in obedience to man’s command, becoming the first conveyance, shortly to be followed by the wheel that would engender the cart and a life of servitude for future equine generations.

He came to New York a few winters ago, adapting to the harsh contrast of summer heat and scrambling multitudes, hoping to carve out a solid path in the nebulous art world, keeping it real, solid as the ice on a winter pond up north. Nick’s own physique matches the powerfully muscled steeds in his work. Both man and beast have the kind of torso that might, to paraphrase Raymond Chandler, “make a bishop kick a hole in a stained glass window,” not to mention incite a long list of photographers to freeze and frame them in their lenses. Why not? Physical beauty is so ephemeral it must be caught on the hoof, laid down in pencil, paint, and prose, on film and digital, as rapidly and purely as possible. And besides, these days you need biceps as well as concepts to muscle your way through the art world.

The artist shivering in his unheated barn thinks of the nineteeth-century English painter George Stubbs in his slaughterhouse of a studio, studying the decaying musculature of a dead racehorse, careless of the stench. Turner hunkers down and works on, equine mysteries materializing from the tip of his sable brush. Spring will come, the ice will thaw, and horsemen will ride.