Life After Omar

LIFE AFTER OMAR

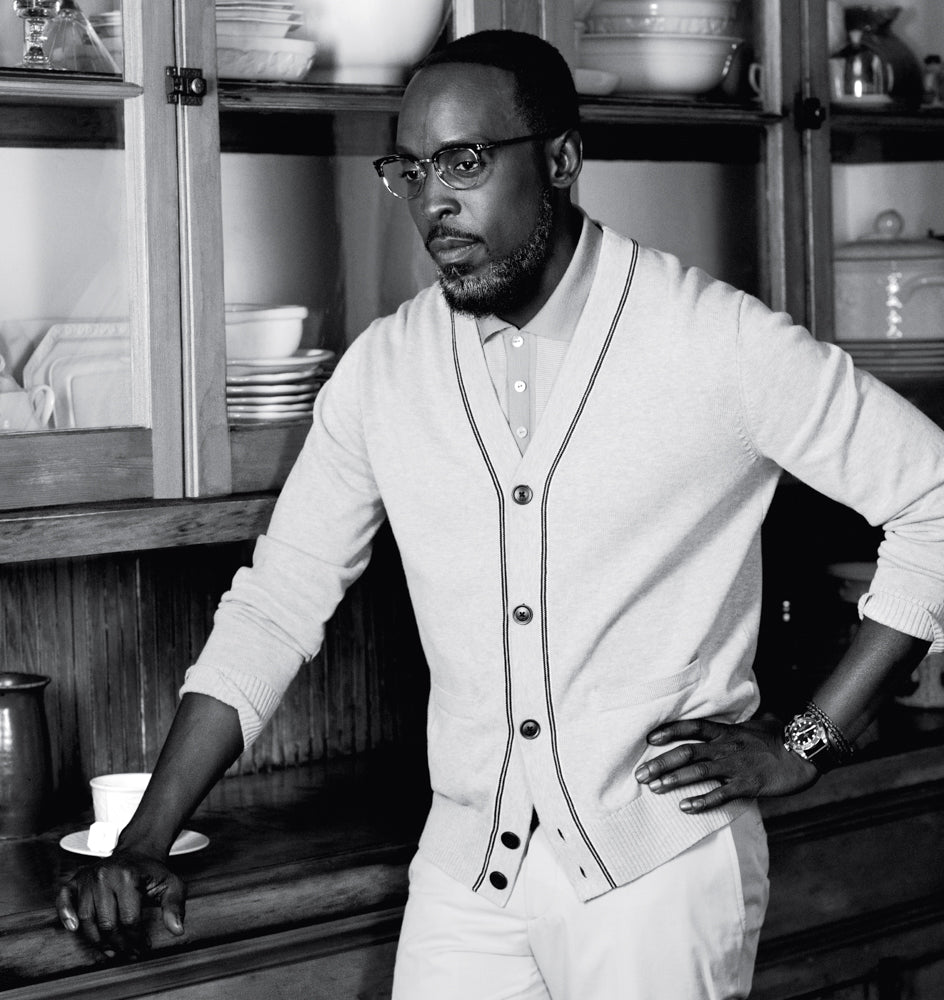

Actor Michael K. Williams is more than the sum of his parts

On a brutally wintery Saturday morning in New York, Michael K. Williams was holding court with his team over a pot of hot tea at the Crosby Street Hotel’s bustling restaurant. Williams, wearing a cozy Scandinavian sweater, an American-flag scarf knotted around his neck, was seated at a large round table where it was hard to not notice him. People were coming and going. Unlike his two most famous characters, Omar Little from The Wire and Chalky White from Boardwalk Empire, known for their bottled-up menace, Williams is an easy, intimate conversationalist — he’ll touch your arm to make a point — and by late morning, after all this talk, things were running an hour or so behind schedule, the hotel’s lobby sofa doing double duty as his waiting room.

Williams took a circuitous path toward being overscheduled in posh Soho, starting out life in the Vanderveer Estates housing project in Flatbush, Brooklyn, and attending the same hardscrabble high school, George Westinghouse, that produced Jay-Z, the Notorious B.I.G., Busta Rhymes, and DMX. He spent stretches trying to find his way as a club kid, community college business major, backup dancer, and, for a few scary years when he disappeared into the cracked-out warrens of downtown Newark, a perilous drug addict. Fellow users knew him only as Omar.

And yet here he is, clean, prosperous, and engaged, with a gray-tipped beard. The famous scar that divides Michael K. Williams’s handsome face in two is, at least in the midday light, even more profound — almost tectonic — than it appears onscreen. Some guy with a razor cut him on his twenty-fifth birthday, apparently randomly, at a bar in Queens. These days, he lives in Williamsburg. If you want a quick summary of his personal myth, his Instagram handle is @BKBMG, which stands for Brooklyn Boy Makes Good. It’s a slideshow of affirmations (“It is easier to build strong children than to repair broken men — Frederick Douglass”), pop-culture enthusiasms (Cookie from Empire), and celebrity friendship (shots of him at the Selma premiere wearing an “I can’t breathe” T-shirt, posing with David Oyelowo, Questlove, and Aretha Franklin). In the last few years, he’s had roles in 12 Years a Slave, Robocop, and as Rick Ross, the infamous LA crack kingpin, in Kill the Messenger.

His big post-Wire gig, in Boardwalk Empire, ended last year, but he was in two very good films this past winter: Inherent Vice and The Gambler (not to mention a bloody role in his old friend Ghostface Killah’s melodramatic new video for “Love Don’t Live Here No More”). Soon he’ll star in the HBO miniseries Crime, where he plays the inmate Freddy, who he describes as “a lifer who runs Rikers Island.” The series is about what happens to a person when they go to jail. How do they come back out? The plea bargaining, what happens in the lives inside those walls, about how the jail sentence affects the family outside.”

“I thought all my emotional scars would be gone once I got there, and all it did was shine a light on them.”

In March, he stars in an HBO film about the life of blues singer Bessie Smith, opposite Queen Latifah. He plays her abusive husband, Jack Gee, who “although I believe he really loved her, he was a manipulator and a hustler,” says Williams. “He’s kind of recorded as being the main reason she hit a wall when she did, as the guy who ran her career into the ground.”

He’s known Dana Owens, now known as Queen Latifah, since they were teenagers, “just two kids running in the street,” he says. In the mideighties, she’d come in from Jersey, he from Brooklyn, to hang out in Manhattan’s Washington Square Park. “Any excuse to get out of the projects,” he says. “So we met there, and I took a liking to her, and I would always notice that at a certain time of night, she would have to leave, to catch the last bus home across the Hudson.” He gave her a key to his apartment since the subway to Brooklyn runs all night. “So we went from street friends to friend friends, and we were in my apartment one day, smoking weed, and she was like, ‘I’m going to get a record deal one day.’ And I was like, ‘Sure, here, hit this.’” He mimes passing a joint to me across the table, holding his breath to keep the imaginary smoke in.

“That’s around when I started struggling with substance abuse,” he says. “I went away for thirteen months, and when I came back home, I went looking for her. And everybody was like, ‘Dana’s on the radio. Her name is Queen Latifah now.’ I was like, ‘Holy shit!’ I mean, chick was serious. But that was the best thing that ever happened to me, because she inspired the hell out of me, and still does. I was determined to not let her leave me behind.”

Although he flirted with a less artistic life — at one point even landing a job at Pfizer — Janet Jackson’s “Rhythm Nation” inspired him to become a backup dancer, putting his club-kid skills to work. He danced behind Madonna, George Michael, and Missy Elliott and toured with a bunch of house acts: Crystal Waters, CeCe Peniston, Technotronic, among others. One day, Tupac Shakur saw his picture while he was putting together a movie called Bullet and decided that Williams “looked thugged out enough to be his little brother.” That chance casting convinced him to pursue acting.

And then he landed The Wire. The gay stick-up guy Omar Little made him famous, but almost destroyed him, too. “In the beginning, it started out as something healthy, and it turned into something not so healthy. I came from the projects, poverty stricken and angry, with a lot of resentment, and I was taking all of that and putting it into the character, which is why I think it felt so real. I always tell people, ‘Do you have any idea how dark a state of mind I must have been in to portray a character like Omar to that level?’ I was all kinds of fucked up in the head.” When it was over, “I wanted to stay Omar,” he says.

Who didn’t love Omar? Shortly before being elected president, Barack Obama himself called him his favorite character — “the toughest, baddest guy” — on his favorite show. (One wonders if, when things get rough in the White House war room, he doesn’t sometimes ask himself: What would Omar do?)

The message here is an old one: fame won’t solve all your problems. It also won’t make you into someone you’re not. Williams might play a lot of tough guys, but they’re really not who he is. “I was corny growing up,” he says. “I was the kid who got picked on. So to go from that and to not have dealt with that part of my life personally, to then be thrown into the fame — or the popularity, I should say, of Omar — was crazy. I went through a very dark period when they killed that character, took him from me. They took my best friend. I had thought, I’ll get successful and I’ll be happy. I thought all my emotional scars would be gone once I got there, and all it did was shine a light on them.”

“I understood Omar’s heart, same as I understand Chalky’s heart, and I understand Jack Gee’s heart.”

But now he’s come to terms with what it means to be an actor; realized the actual purpose of his fame. “I want to move people. I want to touch people I don’t even know,” he says. “Because Omar was very real to me, I was able to do that. Different aspects of his life were taken from people that I knew or know. I understood his heart, and that’s where the compassion comes from. I understood his heart, same as I understand Chalky’s heart, and I understand Jack Gee’s heart. I know where it comes from — from my ancestors, from my elders who I grew up around, from people that I came up with.”

It’s about empathy, even for characters who aren’t, to most Americans, all that sympathetic. It’s the same reason he helped produce a raucous indie documentary about an Atlanta drug dealer, Snow on tha Bluff, in 2012. Its star, Curtis Snow, who Williams first heard about on Twitter, “kinda reminded me of Omar,” he says. He felt like his story illuminated a truth about America that's usually hidden. Williams was also recently appointed the ACLU ambassador for the organization’s campaign to end mass incarceration. “People are being thrown in jail and being made felons for low-level drug charges — nonviolent, low-level drug charges. People who have drug addictions, people with mental illnesses, are being turned into convicted felons. And it seems like almost everybody being thrown in jail is brown. Everybody’s not a felon, you know? That kinda thing follows them around for the rest of their lives.”

Bessie Smith’s story had its ups and downs, too: in the 1920s and early thirties she was the highest paid black entertainer in the world, touring the country in her own railroad car. But she made some bad decisions, and had some others made for her by people, including Gee, and died, rather tragically, in a car accident in 1937.

“To still be rockin’ on this level, you can’t tell me there’s no God.”

I asked him if once Latifah decided she could do the film, she called him up and asked him to sign on. “Ha, I wish it were that easy,” he says, smiling ruefully. “I had to bust my ass in the auditions. There’s no nepotism with her.”

But he’s glad to be working with his old friend finally; it has a certain satisfying circuity to it. BKBMG, indeed. “We spoke for, like, two hours on the phone the other night,” he says. “I was like, ‘Dana, you really don’t know what you did for me. You were the first tangible thing from our world that I saw make something of themselves. You let me know what to do. You let me know it could be real, and then, on top of that, you never shunned me, even when I was still rocking and rolling. You always made time for me, even as your star was rising.’ She used to give me pep talks: ‘I see you, brother, I see you. Do your thing.’ It was my dream to work with her one day.

I thought I’d be a background dancer, and I thought I’d be spokesperson for her clothing line, and then when I became Omar on The Wire, you couldn’t tell me what we wasn’t going to do. But it was in God’s time, and it happened in the form of Bessie Smith and Jack Gee. So this film is more than a job for me. It’s a three-sixty. She and I, we look back at our past and all the people that we knew as kids who are no longer here for whatever reason. For her and me to be still rockin’ on this level, you can’t tell me there’s no God.”