J.B. Blunk House

J.B. BLUNK HOUSE

“Wood also populated the landscape in which he would eventually settle with his family. His best-known works often involve massive slabs of the stuff and frequently employ the creative use of chainsaws.”

Given the nature of his work — predominantly large-scale sculptures hewn out of wood or assembled from natural materials and found objects — it makes sense that the home of J.B. Blunk would not only share the late artist’s defining aesthetics, but actually serve as that aesthetic writ large. A quintessentially Californian sculptor, ceramist and craftsman that came into his own during the 1960’s, Blunk’s best known pieces made use of wood — particularly, redwood — a medium that not only clearly fueled his imagination, but populated the landscape in which he would eventually settle with his family.

His best-known works often involve massive slabs of the stuff (and frequently employed the creative use of chainsaws), but the rough and tumble nature of his process in no way made his work any less erudite or elegant. Iconic works like “The Planet” — a massive 13-foot structure carved entirely from a two-ton redwood burl — are nicely indicative of Blunk’s vision; objects that both alter, enhance, and ultimately celebrate natural forms. Though he would create a great number of public and private works during his five-decade career (all of which remains highly regarded and profoundly collectible today), ultimately Blunk’s boldest and most personal artistic statement remains his own home.

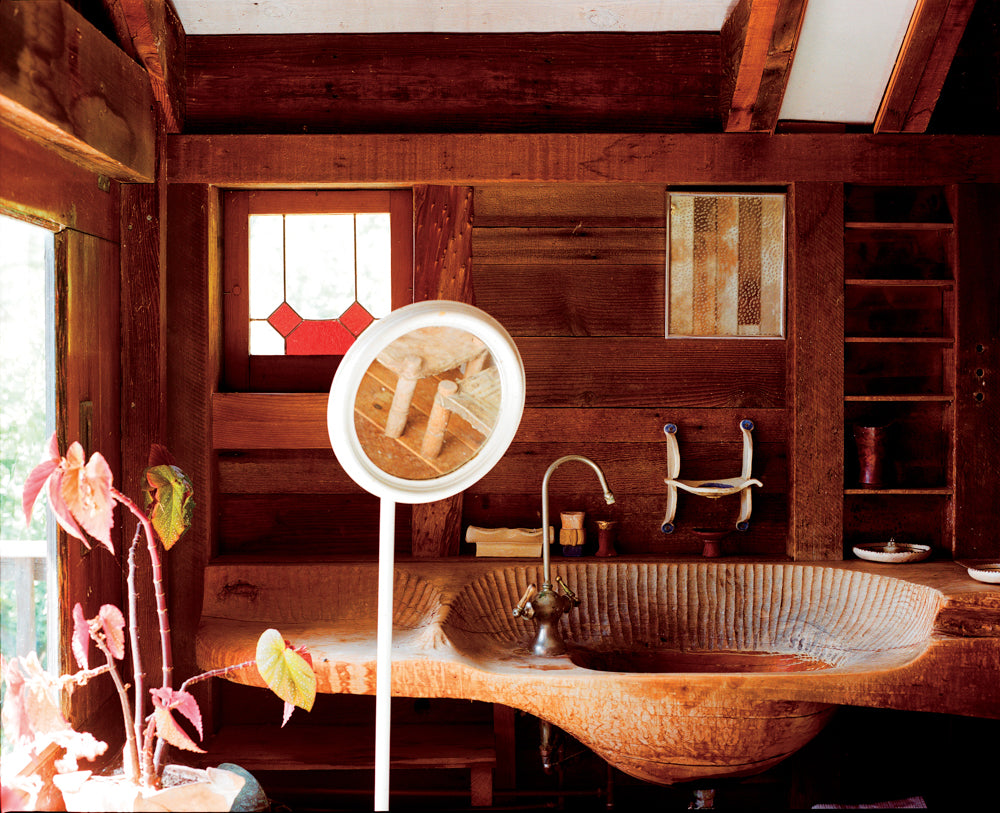

Constructed between 1957 and 1963 in California’s Marin County, the Blunk house was born as a functional work in progress between Blunk and his first wife, Nancy Harlow. Located near the top of Inverness ridge — overlooking Tomales Bay — the house was begun on a budget of $1,000 and slowly pieced together using scavenged materials — old windows, discarded doors, driftwood, and the odd pieces of detritus from Blunk’s own sculptures. In many ways, the house itself evolved like one of Blunk’s pieces — less dependent on traditional carpentry and more like a large-scale version of one of his assemblages. According to Blunk’s daughter, Mariah Nielson, the materials used in the house are an essential part of its DNA.

“There are redwood piers originally from docks in the Sausalito Marina which were used as beams and columns in the house, and old doors which he used as windows,” says Nielson. “There are several door handles which are made from tree branches and light pulls whittled from wood scraps. My favorite feature in the house is a wall made from redwood fall-offs (mostly scraps or left overs) from his sculpture “The Planet”, which he made in 1968-69 for the Oakland Museum in California.”

The interior of Blunk’s modernist cabin remains much as it did when he originally constructed it. In addition to the array of repurposed windows, bits of stained glass, and unusual architectural touches — a huge sink carved entirely out of redwood, for example — the one-room space provides a perfect, almost religious, environment for Blunk’s minimalist furniture. In fact, the house seems the most perfect vehicle for expressing what seemed to be the artist’s constant intent — to expose the secret life that seemed to be hiding within his materials. In a 1999 interview with Woodwork Magazine, Blunk explains: “My way of working, the core of all my sculpture, is a theme,” he says. “It is the soul of the piece. Sometimes it is evoked by the material; sometimes it is an idea or concept in my own mind. It is always present, regardless of the material, size or scale of what will be the finished piece.”

“The house itself evolved like one of Blunk’s pieces, less dependent on traditional carpentry and more like a large-scale version of one of his assemblages.“

From 2008 until 2011, the house operated as an artist residency run by the Lucid Art Foundation though these days artist Rick Yoshimoto – Blunk’s assistant of over twenty-five years – uses the studio — which still contains many of Blunk’s original tools and materials. Though the house is no longer open for public viewing, maintaining the integrity of the space — and the care of its contents — remains paramount for his family. They currently maintain the house by doing exactly what Blunk himself originally did — living in it. It’s the kind of symbiotic art/environment domestic relationship that most people will never get to experience, but one that speaks to the functionality and wonderful sense of purpose that exists in Blunk’s work.

“I was born and raised in the house,” recalls Nielson. “It’s difficult to describe my experience of growing up there as anything other than normal...it was just my world. I thought my friend’s homes in the suburbs were exotic. My earliest memories of the house are playing in my father’s workshop and making ‘food’ out of sawdust. I think that growing up in a house my father made has instigated a deep affinity for craft, design, art, and in general, materials. I am drawn to tactile, well-crafted objects and interiors… and, I guess it’s no surprise that I love wood.”