Hefner At Home

HEFNER AT HOME

The birth of the modern bachelor pad

When Hugh Hefner was drafting the image of the ideal Playboy reader — a literate and liberated sort, who also enjoyed a nice set of cans — his ideas went far beyond silk bedsheets, martini shakers, and one-night stands with stewardesses, a dog-eared copy of the latest Kinsey Report laid conspiculously on the nightstand.

In fact, one of his most lasting contributions to Western culture might be in the realms of architecture and design, areas of interest that allowed him to round out his readers’ world. After inventing the Playboy bunny, he laid the floor plans for another cultural icon: the bachelor pad.

Raised in Chicago amid the buildings of Mies van der Rohe and Frank Lloyd Wright, Hefner was an early champion of midcentury modern. He was also a student of human nature, having earned his bachelor’s degree in psychology at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. “The notion of the single man began in the 1950s,” Hefner told the New York Times. “The idea of the bachelor as a separate life was new and obscure.”

“In my father’s house are many mansions” — John 14:2

Hefner’s erudite interiors were fully automated, streamlined machines for high-end living, with doorless quarters to encourage debauchery. In contrast to today’s man caves and the musty drawing rooms of yore (where men lounged in cracked leather chairs and harrumphed into their cognac snifters), Hefner’s renderings were chock-ablock with gizmos and designed to seduce, with linear open plans so a man could smoke his pipe anywhere he damn well pleased. Remote control in hand, he could also draw the curtains, open the garage door, pop open the wet bar, or click on the hooded fireplace, all from the comfort of his two-piece Eames lounge. You could say Hefner saw his reader, a sort of 007 with a license to lady-kill, as the future of the American man. His reasoning was sound: After surviving the horrors of WWII and Korea, didn’t every guy want a castle all his own?

The classic men's den, a secluded habitat equal parts fantasy and function, radiated out into every room of the house, which was realized in the gorgeously rendered architectural and design drawings that appeared regularly in Playboy’s pages from the early fifties to 1979.

Hef’s bachelor pad renderings, featuring recognizable midcentury furnishings and the entertainment console gadgets of the day, were often accompanied by profiles of the great modern minimalists.

His interest in residential architecture for the upscale single male culminated in the Playboy Penthouse Apartment (designed by Chrysalis architects and featured in a 1956 issue), with its echoes of Neutra and the Eames Case Study House.

But it wasn't until May of 1962, when the magazine published its ambitious pictorial, “Posh Plans for Exciting Urban Living!” that the design world took notice.

“The notion of the single man began in the 1950s. The idea of the bachelor as a separate life was new and obscure.”

The renderings of the so-called Playboy Town House, drawn up by architect and designer R. Donald Jaye and overseen by Hefner, envisioned a three-level luxury spread, which the magazine described as a “modishly swinging manor” for an “unattached, affluent young man, happily wedded to the infinite advantages of urbia.”

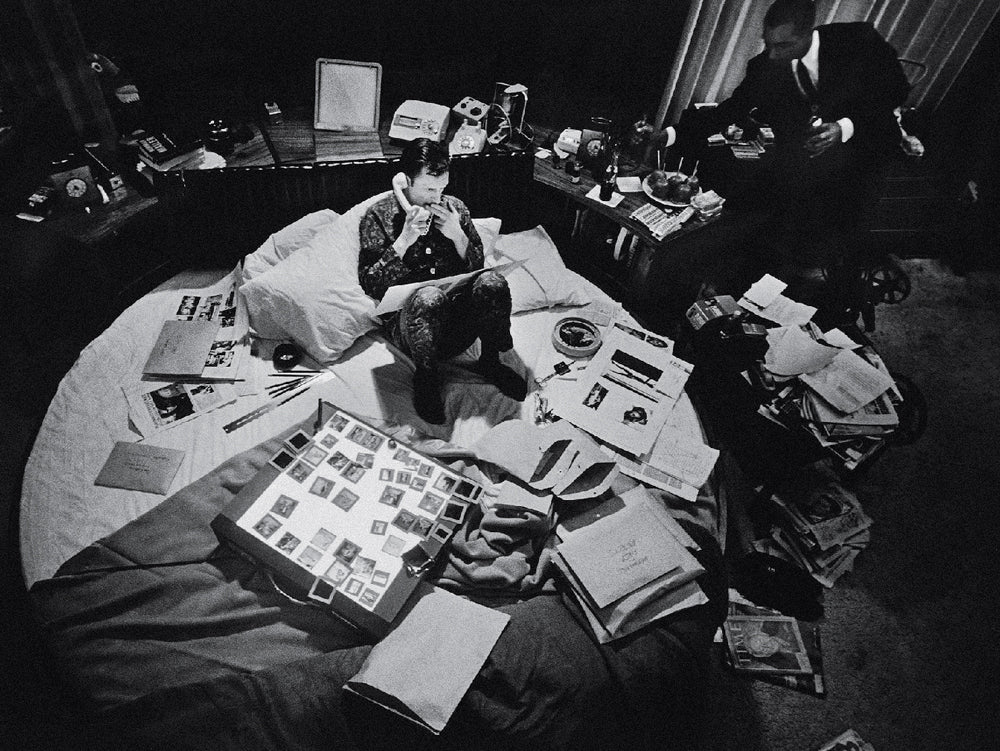

Amid the open-plan sprawl — paneled with enough teak to build a second Honey Fitz, and dotted with curvy furnishings by Knoll, Herman Miller, Laverne, and George Nelson — there were show-stopping amenities like an indoor swimming pool, a remote-controlled skylight, a “kitchen-less kitchen” (where drawers and panels hid any evidence of food prep), a twelve-foot upholstered wet bar (but, of course), and the pièce de résistance, a rotating bed, patented by Playboy Enterprises, for work and play. As the center of his own universe, a man could control sound and lighting, open and shut curtains, and even pop the toaster from his circular love nest. (Later, Hefner would equip the “Big Bunny,” his converted DC-30 jet, with the bed, which had become something of a trademark.) “The gadgetry helped give it a James Bond mystique,” he told the Times.

The Playboy Town House predicted many common twenty-first century residential features, with its open plan and built-in hi-fi system, variously dubbed a “media wall,” “Electronic Entertainment Wall,” and “Wonder Wall.” Inspired by van der Rohe, the house concealed all its wiring, and anything else that might disrupt its streamlined effect. This was a place in which you didn’t trip over clutter. To paraphrase Hefner, a civilized man doesn’t leave his dirty socks scattered about.

“The gadgetry helped give it a James Bond mystique.”

Truth be told, Hefner was never all that removed from his readership. A fantasist who enjoyed vicarious thrills, he lived for a time in his own office, sleeping on a pull-out cot (after his wife tossed him out). Hence the pajamas. And his own homes—both his limestone-and-brick behemoth on Chicago’s Gold Coast and the more infamous digs in Holmby Hills, California — were hardly the stuff of modernist dreams. A fan of dorm-style living and outré touches (his Chicago house bore a plaque on the front door that read, “If you don’t swing, don’t ring,” in Latin), Hef rarely followed his own blueprint.

But others certainly have, and still can. Last year, the German Architecture Museum in Frankfurt featured an exhibition of all things architecture published in Playboy from 1953 to 1979. (Hefner actually donated the original mansion to the Art Institute of Chicago, in 1974; it is now luxury condos.) In 2011, to coincide with Playboy’s fiftieth anniversary, legendary architect Frank Gehry was asked to draw up his own plans for the modern bachelor pad. While spectacular, like most reboots, it just wasn't the same.