Goode Gets Eden

GOODE GETS EDEN

Known for the care and feeding of social butterflies and night crawlers, Eric Goode’s true passion is the humble tortoise.

Eric Goode has steered among the stars of New York nightlife for the past three decades, drenched in the sweet smell of success, as nightclub impresario, restaurateur, and hotelier. And all along, this unabashedly bohemian, California-raised New Yorker has harbored a nerdy little secret: he is an amateur herpetologist, a chelonian fancier, who has collected turtles and snakes as pets since he was six years old. This innocent hobby-turned-obsession has resulted in the creation of one of the largest and most important turtle conservation facilities in the world, the Behler Chelonian Center, located in the foothills of Los Padres National Forest, near the supernaturally mellow town of Ojai, a place so tranquil you can almost hear the oranges ripening on the trees.

The gateway to Goode’s turtle addiction was classic: first a Nabokovian butterfly fetish, then trout fishing. While angling these mountain streams, he began to take notice of the local snakes and lizards. “I really enjoyed hiking in these mountains as a kid,” Goode says, “and I kind of lost myself every day daydreaming and wandering up there, and in the process I began to understand what it’s like to really be in nature. It was just so cool when I came across, say, a species of snake that I had never seen before. After a hundred hikes, when you suddenly have this encounter, it’s kind of mystical.”

By the time Goode was a teenager he realized that he didn’t like killing fish, or feeding mice to snakes. “Tortoises were kind of cool, this animal that just eats vegetables and greens. They also live a long time and are quite rare, which the collector in me appreciated. I also liked the fact that you can keep them out in the garden — they won’t wander off the way a snake would.”

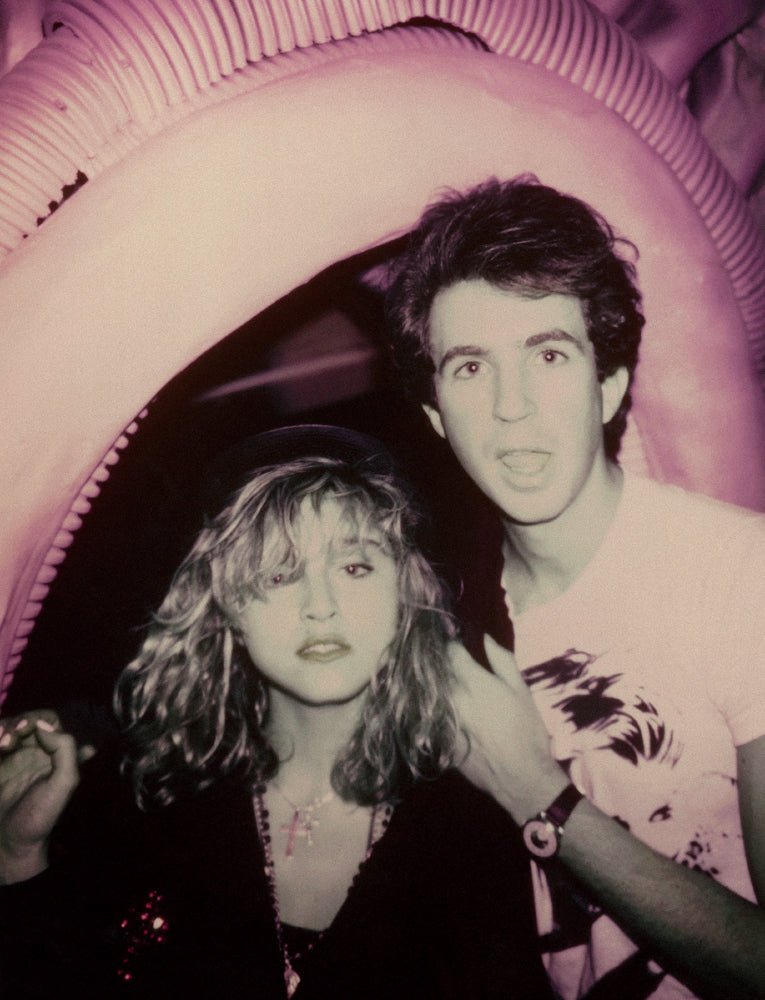

At eighteen Goode left his menagerie to his mother’s tender mercies, while he headed east to conquer New York. After a short stint at Parsons School of Design and a hundred nights at Studio 54, Goode was fully adapted to the party life, and to the idea of life as a continuous party. After a brief return to California, New York quickly lured him back, and he settled here permanently in 1978, with close friends and siblings who’d also gone east. The set up a house below Canal Street, in an illegal loft a block away from the Mudd Club, and soon found work designing sets for its mercurial owner, a former ambulance driver named Steve Mass. Goode’s core group began throwing theme parties at their loft; recognizing a vast untapped audience for any weird combination of art, music, sex, and drugs, they decided to find a place to stage their own events. By early 1983 they had managed to persuade some starry-eyed backers that the concept of the nightclub as art was a winner.

And indeed this oddball idea was destined to become the legendary Area. Operating more as artists than entrepreneurs, Goode and his crew of like-minded lunatics began to create a series of extraordinary happenings at the industrial space they had rented on a deserted block in western Tribeca, where, coincidentally, the eccentric landlord allowed his pet Siberian tigers and wolves to roam the empty building.

The Area years were “pure madness,” filled with brilliant ideas, a great deal of bad behavior, some easy money, and many a disheveled dawn chorus warbling through the empty streets of lower Manhattan. Goode can spin hilarious and fantastical-sounding tales about this period, involving many exotic and boldfaced names, stories alas too libelous for this publication — perhaps when he completes his long-awaited memoir readers will get an insider’s look at New York nightlife’s seedy underbelly. Fortunately, the vast archive he and his sister Jennifer managed to preserve has now been documented in a very handsome book, Area: 1983–1987 (Abrams, 2014). Of course, not everything they made was saved. A large number of wooden boxes that Jean-Michel Basquiat painted for an installation that echoed Warhol’s Brillo boxes were broken up and thrown into a dumpster when the installation came down. But who knew then that all this instant art would one day become so expensive? (Only Tony Shafrazi.)

Shortly after Area splashed down in the Big Town, Eric was interviewed by Andy Warhol’s Fashion, a staple of Manhattan broadcast television. The titular host asked Eric what he would do with all the money he was making, and Eric, already awed by the presence of his idol, replied with startling candor, “Well now I’ll be able to buy some turtles… ” Andy thought Eric was joking, but he was deadly serious. Despite the club’s success, Goode was also worried about telling his unconventional artist father that three of his kids were in “business.” As he recalls in Area, “it would have been as bad as telling him I was a drug addict, or even worse, a lawyer.”

Goode didn’t become a lawyer, miraculously survived the eighties, and continued his involvement with the downtown club world with partnered ventures like MK and B Bar, eventually progressing to the current lineup of discreetly cool hotels: the Jane, by the river on West Street; the Maritime, once a Catholic home for runaways on Ninth Avenue; and the Bowery Hotel, an elegant upstart on a street that once featured only twenty-five-cents-a-night flophouses.

Fueled by these high-end resources, the small walled garden in a California orange grove has expanded into the Behler Chelonian Center, a superbly landscaped five-acre estate with a spacious main home, luxurious guest quarters, modern offices, and a series of closely observed enclosures and greenhouses filled with endangered turtles from Somalia, Burma, Madagascar, South Africa, and many other points of origin.

Goode’s involvement has gone far beyond the humane salvage of a few live animals. An extensive breeding program is in place that is successfully producing large numbers of hatchlings, which in turn may eventually be transferred to other conservation organizations. Goode even envisions a day when captive raised turtles are released back into their natural habitats, although the execution of that plan is fraught with difficulty.

“If we could just slow down to the turtle’s pace, we might live as long as they do. Unfortunately, I don’t practice what they teach.”

“Eric, be gentle!” scolds head keeper Christine Light, who resembles a classic California blonde but actually hails from the borough of Queens, as Goode turns a dozen radiated tortoises on their backs, rather too roughly in her opinion. But Goode’s touch is professional, easy. Today he is testing a new theory to determine the sex of these tortoises. When Good reports back to the naturalist and veterinarian Paul Gibbons, the managing director of the center, the self-taught Goode’s theory that the curvature of the radiata’s plastron, or underside, is key to divining its sex is judged to be “not proven.” Gibbons is still frequently astonished by Goode’s eccentric management style, the strange swirl of natural science and celebrity that he inhabits, but has come to believe in the Eric Approach.

“I’m willing to prostitute myself in any way to make things happen,” says Goode, only half joking, and indeed the center is constantly working on grants, land deals, rescue operations, all devised with a combination of science, business acumen, and raw chutzpah, the end result profiting nothing but the animals. But Goode’s languid, laid-back California style is deceptive. He comes on like an easygoing naturalist, totally engrossed in the fate of endangered turtles. But when he is observed directing operations by remote control at the Bowery Hotel while simultaneously negotiating to buy a piece of turtle-occupied desert in Mexico, or charming an irascible American collector of tigers into granting him an on-camera interview, another, tougher side of his apparently innocuous personality begins to emerge. That hardheaded aspect quickly retreats behind a carapace of friendly banter as we induce the Galápagos tortoise to race the African spur-thighed tortoise that shares her pen for a prize of carrots and lettuce leaves.

He has had the Galápagos for thirty-five years, a friendly female of about three hundred pounds who allows a visitor to stroke her leathery neck. “If we could just slow down to the turtle’s pace, we might live as long as they do,” Goode says, wistfully. “Unfortunately, I don’t practice what they teach.” To a New Yorker just flown in from a subzero East Coast winter, that slower mode sounds like an attractive proposition

Today the core team — Goode, Gibbons, and scientist Ross Kiester, who also coedits Goode’s magazine, The Tortoise — are celebrating the addition to their board of directors the legendary mountaineer Rick Ridgeway, who will contribute some serious conservationist muscle to their cause. In the course of persuading Ridgeway to come aboard, Eric hiked up a small mountain with the iron-limbed explorer — he managed to keep up the pace but had to soak his legs in Epsom salts for four days afterward. “It was worth it,” says Goode, massaging his still tender calves. He is also unafraid to enlist the services of his many celebrity friends, freely mixing the rich oil of nightlife with the somewhat purer waters of animal conservation.

His latest side project is a film about the wildlife trade, a peculiar but highly profitable business that has already taken Goode and his crew to some very strange places — including Tippi Hedren’s Shambala Reserve, where the tiny actress dwells happily with her pet tigers among the meth labs in the high desert, and to a convicted murderer’s animal trading post in south Florida. Goode feels very comfortable in this bizarre subculture, even when his host is demonstrating his latest acquisitions of endangered wildlife and industrial-grade weaponry.

Goode acknowledges the difficulty of trying to change cultures that have been using tortoises, endangered or not, as medicine and food for thousands of years. He is determined nevertheless to make a mark, construct a few little arks that will hopefully stay afloat in an increasingly hostile environment. “I try to stay very focused, because you can only do so much in life. To buy a few parcels of land and protect a few species, if I can do those two things right, I think I have done a pretty good job.”