Devil’s Advocate

DEVIL’S ADVOCATE

A PHOTOGRAPHER’S QUEST TO SAVE THE PLANET’S MOST TERRIFYING PREDATOR

Michael Muller was ten when his father bought him a Minolta Weathermatic, a gaudy, yellow hunk of plastic that was state of the art in underwater photography at the time. His imagination quickly outpaced his access to subjects, and among the first photos he took was a snapshot of an image of a shark from the pages of National Geographic. Aspirational if not exactly honest, he told his awed classmates he’d shot the photo himself. The ruse didn’t last long, and he soon admitted that he had not, in fact, learned to scuba dive while they were at recess. But the shark photo proved a Rosebud moment.

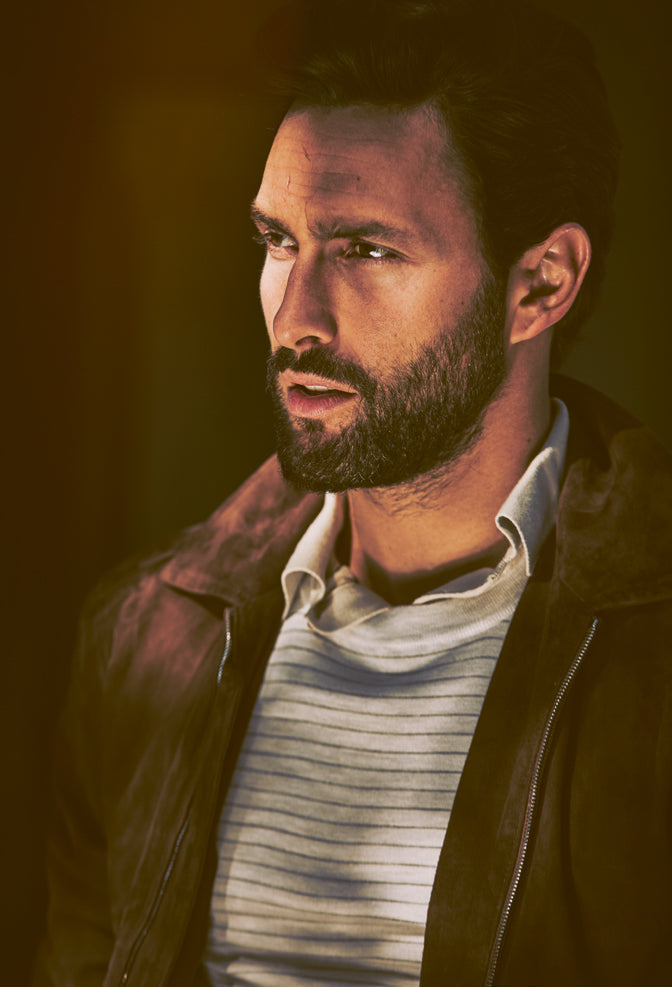

“That was the first time that I really saw the power of photography,” he tells me at a café on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. In the decades since, Muller has built a career as one of the foremost wielders of that power, a top-shelf editorial and advertising photographer and Hollywood’s go-to lensman for ubiquitous movie posters and celebrity portraits. He is in town to shoot promos for Zoolander 2 the next morning, and as we talk a city bus rolls by on Allen Street, its side plastered with an ad for the film Deadpool. “That’s one of mine,” he says with pride.

But it is sharks we are here to discuss, a subject Muller has come back to with his forthcoming book Sharks: Face to Face With the Ocean’s Endangered Predator, out April 1 from Taschen. The culmination of a decade-long obsession with these apex predators, it contains hundreds of photos, shot in a beautiful, haunting style that takes its cues from Muller’s studio work rather than National Geographic.

It’s also a project with a higher purpose: to change people’s perceptions of sharks and draw attention to their plight — an estimated one hundred million sharks are killed each year, primarily to supply the demand for their fins and other body parts. A master at getting and holding a viewer’s attention, Muller was convinced he could use his artistry to make people take a second or third look at an animal they already think they know. “It was like, what can I do?” Muller says. “Well, I’m a photographer, I can use my skills to change people’s perceptions and to raise awareness about the number of sharks being killed.”

It takes a certain amount of confidence to believe you can coax something new out of actors who have spent their lives in front of a lens. It takes confidence bordering on insanity to believe you can take the same methods that have led to success in studio shoots, bring them deep underwater, and achieve portraits that will reorient the public’s Jaws-infused understanding of sharks. And yet that’s what Muller set out to do.

But let’s back up. It was ten years ago that Muller’s photography once again intersected with sharks when, as a birthday gift, his wife booked him to go cage-diving with great whites in Mexico. Muller has always been adventurous, finding outlets for his restless energy in things like triathlons (he was a topranked triathlete in the late 1980s) and snowboarding (he was a published snow-sports photographer by the time he was fifteen). He’s long used action sports and adventure projects as a counterbalance to his more polished studio work, so it was perhaps unsurprising that something in the experience of diving with sharks appealed to him immediately. “That was a full tourist trip,” Muller says.

“But from the moment I first saw a great white and locked eyes with it, I wanted to be out of that cage. I wanted to interact. I really, really wanted to swim with those things.” He also wanted to photograph them, but not in any way it had ever been done before. “I wanted to do something new, something unexpected,” he says. “You can’t bring the shark to the studio, so I thought, ‘We’ll bring the studio to the sharks.’” He had been researching underwater lighting for a Speedo campaign he was shooting, and was taken with the idea of using studio-style lighting underwater to illuminate the animals. But the main commercially available lights were 400-watt strobes, which were insufficient for the task of lighting what he calls a 15-foot-long “SUV with teeth.” So he began trying to figure out how to bring more powerful 1,200-watt strobes underwater.

After several false starts, Muller found someone who could make the kind of underwater housing he had in mind, allowing him to bring the strobes more than one hundred feet below the water’s surface while they remained tethered to a power source floating in a boat or on a jet ski. The prototype lighting system was delivered the day before he left for a shoot in the Galápagos with the watch company IWC, for which several of his assistants got their scuba certification. The trip was proof positive that the system worked. “We spent fourteen days on the water down there and came back with just phenomenal photography,” he tells me. “That trip was where this whole thing started. The fulfillment I felt in the Galápagos was just a fulfillment I’d never felt with any of my other photography. It was bigger than me,” he continues. “It was like, this is our planet, these animals. And from there, it took over.”

He eventually got several patents on the lighting system, and spent years alternating commercial shoots with increasingly sophisticated, self–financed shark dives all over the world. As Muller and his team honed their system and built an impressive body of work, he became more comfortable swimming with the animals, mostly without a cage or metal suit. The project grew in scope from great whites to all sharks as Muller began thinking more about a book that would unite his images with a strong conservation message. He began bringing celebrity friends like Ben Stiller on shark dives to draw attention to the plight of the animals, and eventually he found the perfect partner for the project in Taschen. The resulting book unites Muller’s shockingly original images of sharks with essays from conservationist Philippe Cousteau Jr. and marine biologist Dr.

Alison Kock, as well as pages of species notes, shark-related statistics, and lists of resources for further information and shark conservation organizations for readers to support. There are also some incredibly disturbing shots of the blood-soaked “finning” of captured sharks, which Muller shot in the Persian Gulf. “They started pulling the sharks out, hacking the fins, and I just got up in there. It was one of the hardest things I’ve ever filmed,” he says. But Muller wanted to make sure it was in the book so people would understand that we are a far greater threat to sharks than they are to us. “By the time that shark fin reaches Beijing or Hong Kong, it’ll sell for $200,” he says. “It’s more lucrative than drugs.”

The irony at the core of Muller’s book is that, for all it accomplishes in redefining how we see sharks and in making them more accessible to a general audience, the images succeed largely because they carry the whiff of menace. These are powerful, perfectly designed predators, stunningly photographed and worthy of protection. But they’re still a little terrifying. And that’s sort of the point: the photos bristle with the power of the sharks and are suffused with the implied bravado of the act of photographing them.

It was on a recent dive, he says, after he and his videographer had a brief face-off with two great whites, that he came to some clarity about what draws him to these creatures. “It finally hit me,” he says. “When you’re with these sharks, especially great whites, it’s the purest form of being in the moment I have ever experienced. You’re not thinking about anything else, and I was like, ‘This is why I do this.’”