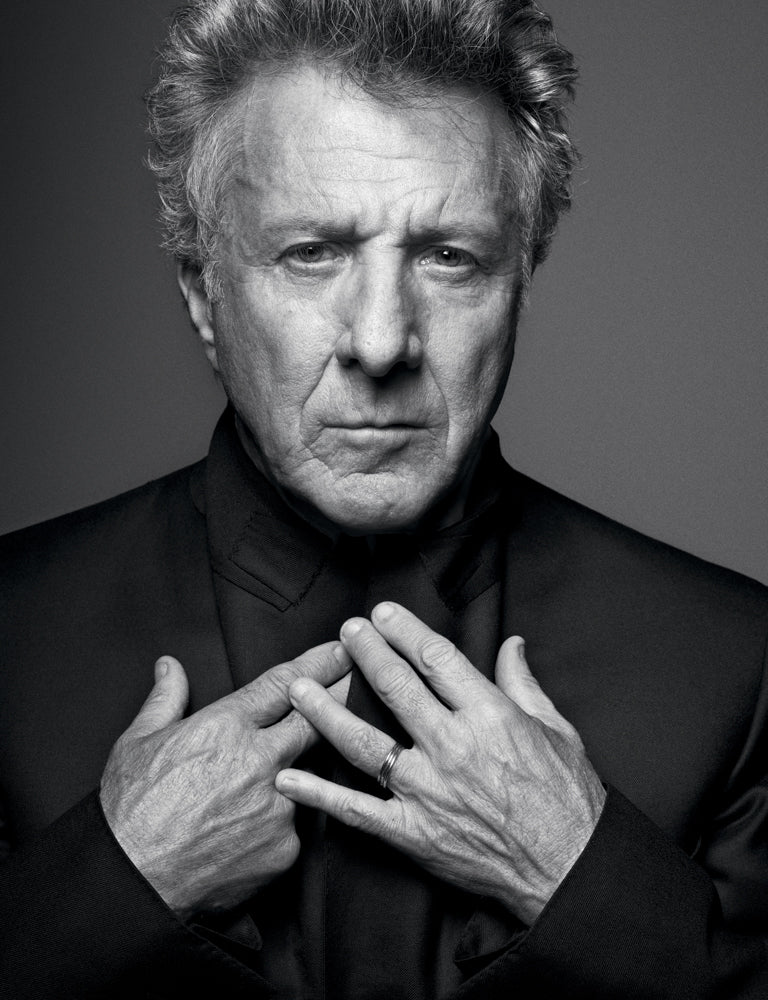

Dennis Hopper. The Art Of Life

DENNIS HOPPER. THE ART OF LIFE

“I’m not sure how my visual art and my movies will be seen in the end, but I think the work I’ve done is at least interesting. What I hope is that it’ll all come together in an interesting story in the end. I don’t think there’s any way to separate it. ” — Dennis Hopper, 2009

The last time I visited with Dennis Hopper, he told me to take peyote. He put his hand on my shoulder, leaned in close, and whispered in my ear, “God is in the cactus, Jessica. God is in the cactus.” It was the fall of 2009, the tail end of a three-year journey to produce a monograph of his photos for Taschen. I had spent dozens of hours interviewing him by then, trying to act blasé as he recounted his cosmic sprint through the post-war zeitgeist: Befriending James Dean on the set of Rebel Without a Cause; marching with Martin Luther King Jr. in Selma; throwing parties for Andy Warhol at the dawn of the Pop Art movement; tripping balls in the desert with Jack Nicholson.

He had asked me to his office in Venice to review my finished manuscript, which he proofread while I watched. A few pages in, he looked up and laughed: “Is anyone even gonna be interested in all this?” I rolled my eyes and assured him they would be. “By the way,” he asked. “You ever taken peyote?”

Dennis Hopper was an exceptionally talented actor and director, a gifted photographer, and a world-class art collector; a counterculture infiltrator who pissed inside the tent at a time when back talk could get you blacklisted. He didn’t start out that way, but learned from the best after meeting James Dean. “Jimmy was the most talented and original actor I ever saw work,” he told me. “You’d never seen acting like that! He was a guerilla artist who attacked all restrictions on his sensibility.”

His friend James’s influence cannot be overstated. After meeting Dean, Hopper went from memorizing Shakespeare to full-fledged Method. He freed himself, and began questioning everything. With Dean’s encouragement, he also picked up a camera. For the next fifty years, he rarely put it down. In 1969, he directed and starred in Easy Rider, an acid-laced love letter to his doped-out generation, that blew open the doors of Hollywood for independent filmmakers and made him an icon at age 33. Dennis, the sweet kid from Kansas with the flat top, was a certified outlaw.

He would live on the edge from there on out, among the last of the great madmen — friend to rock stars, art stars, and superstars of all stripes — a sworn enemy of conformity and complacency. By the time I met him, a few years before his passing, he had pretty much done it all. He knew that to be a great artist of any sort, you have to be open to the world. You have to know that God is in the cactus, yes, but in other places, too: The blue of a David Hockney, the sound of a woman’s laugh, the wind in your face as you barrel down the PCH, headed for nowhere.

“I was born in Dodge Сity, Kansas and am really just a middle class farm boy at heart. I really thought acting, painting, music, writing were all part of being an artist. I never thought of them as being separate.”

“The modern, the paranoia of modern life, and objects that were never considered beautiful that are now considered possibilities for art. So popular objects, popular art: pop art.”