David Hockney In The Now

DAVID HOCKNEY IN THE NOW

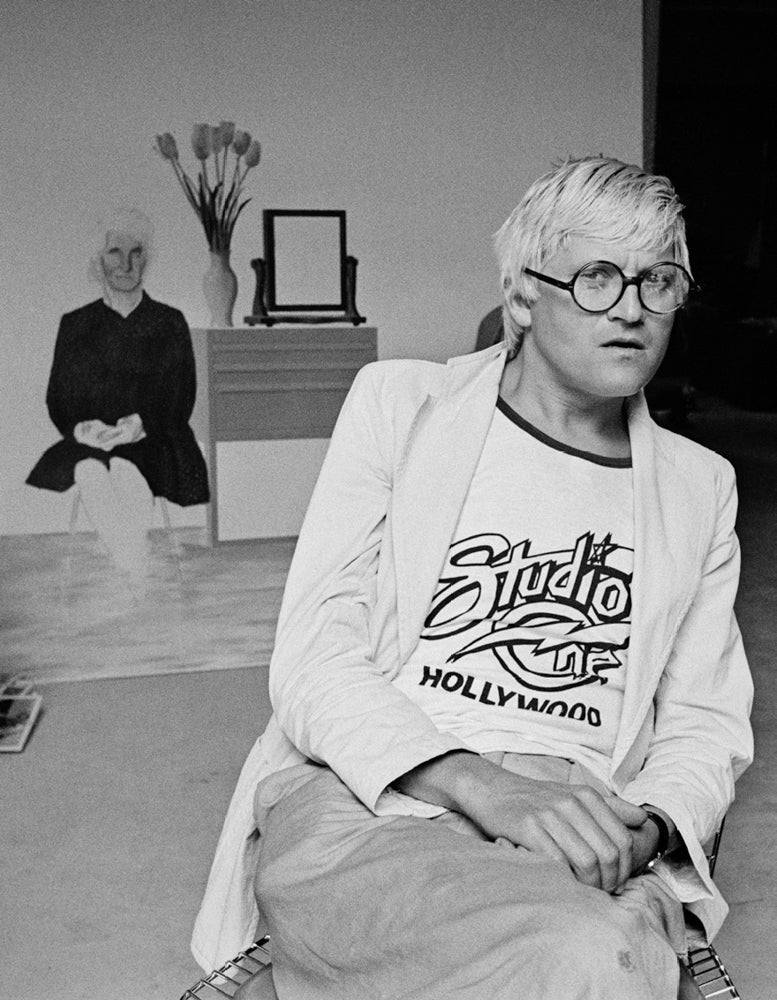

A sign on David Hockney’s studio wall in the Hollywood Hills reads SMOKING AREA. Every place in Hockney’s studio is a smoking area.

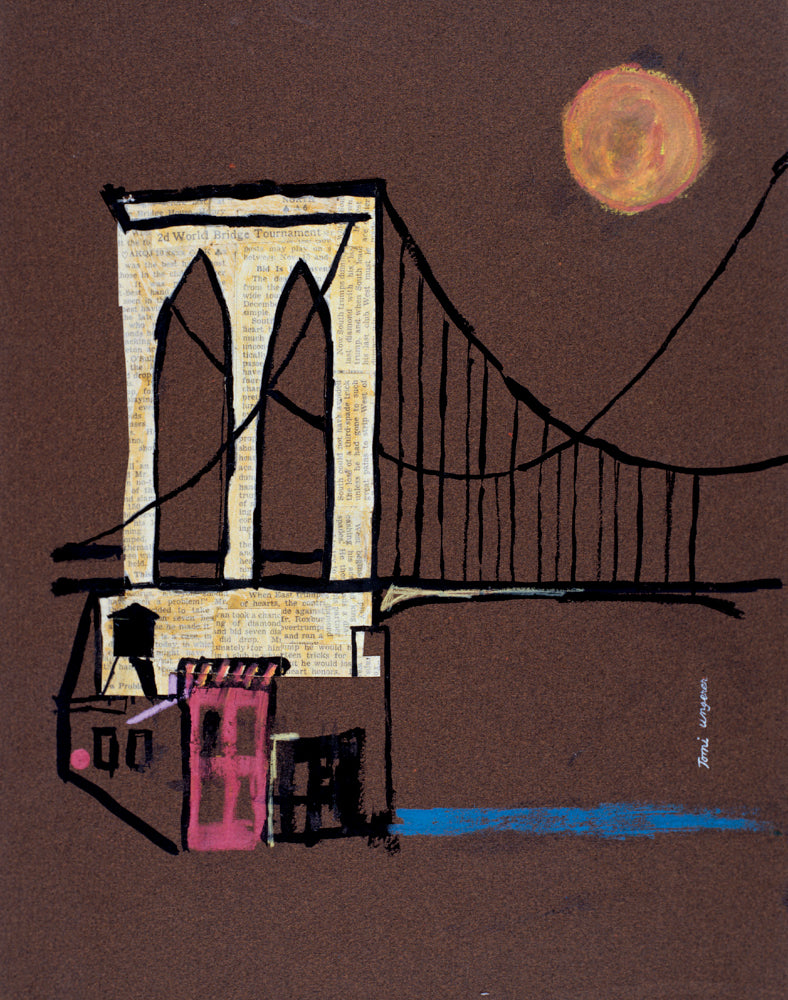

“Photography came out of painting and is now going back to it,” reads another notice, which I am gung-ho to snap with my iPhone — except a further text scolds that photography is not permitted. Most of that wall, though, is occupied by Hockney’s portrait paintings. They are lined up in a single row, the subjects seated in various attitudes on the same chair, and these are among the portraits that will be in a show at London’s Royal Academy beginning July 2. “David Hockney RA: 79 Portraits and 2 Still Lifes” hints at the way that the artist has taken flight somewhat above his hugely talented generation, just as Andy Warhol, also a focus of attention and a market signifier, floated above his generation. As to the why of it, well, that’s one of the things on my mind here in Hockney’s studio.

The portraits for the Royal Academy show are not commissions, so they reflect Hockney’s interests, his friendships, and his roaming curiosity. His subjects, not necessarily up on the wall, include a dear friend and frequent model, Celia Birtwell, who is married to the London designer Ossie Clark. Also depicted are such familiars as his brother, his sister, his housekeeper, Patty, and an assistant, Gregory, who has just walked into the studio leading an English bulldog named Wilbur. There’s Francis Watson, a co-discoverer of the structure of DNA, and solid art-world presences such as John Baldessari, the California conceptualist; Benedikt Taschen, the part-time Angeleno who upended the art-book publishing model; and Larry Gagosian, who did the same for art dealership. Gagosian is not Hockney’s dealer, though. “I’ve known Larry since he had a poster shop in Westwood,” he says. “He used to come and sit in my studio when he was on Santa Monica Boulevard and chat. But he wants to sell everything. I don’t want to sell everything. So I’ve never shown with him.”

As for Taschen, a giant work in progress with the publishing house is sitting in front of us right now, a record of the Hockney oeuvre from 1951 up to this moment. He leafs through it with the glee of the teenager whose precocious work can be seen on the first pages. “I’m not one for looking at the past that much,” he explains. “I’m always concerned with now. I live in the now. But this! This is the seventh version we’ve done. There’ll be just a couple more before we sort it out.” I point out that two or three pictures in the book seemed to surprise him. “Yes. I’ve never really looked back at my work. Not like this,” he says.

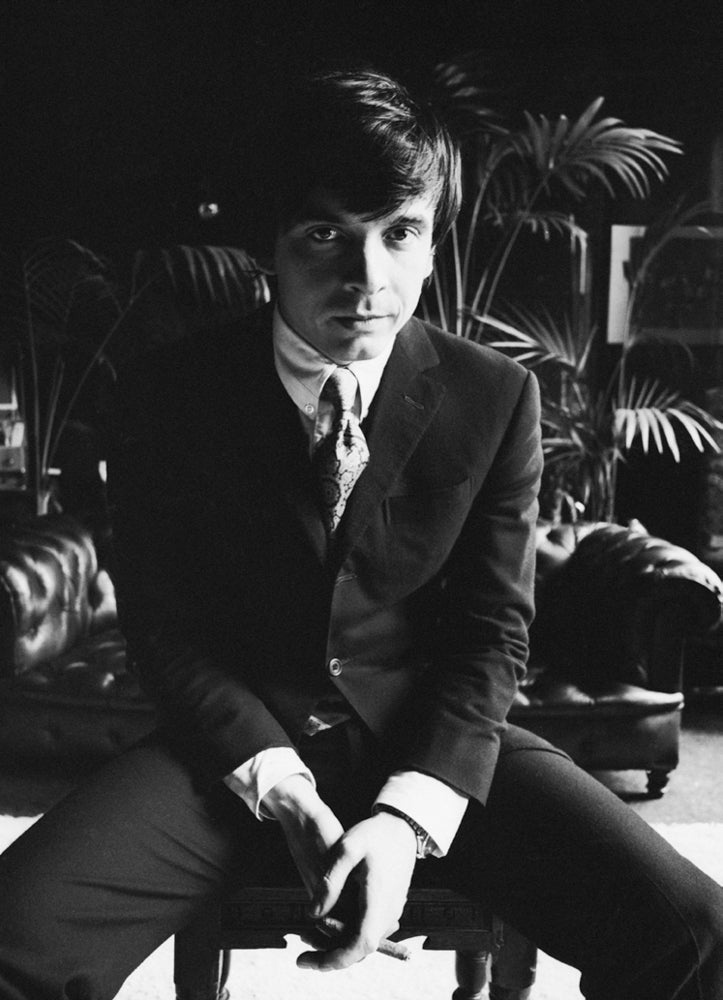

Hockney moved without incident through his adolescence in Yorkshire, England, his taste of success at London’s Royal College, and his first visit to America at age twenty-three. “I went to New York in 1961,” he says. “It was between my second and third year in the Royal College of Art. And that was the first year I didn’t have to get a job. I had sold some paintings. I took about $350, which you could live on then — I mean, not traveling in taxis. I got a bit more money when I sold some etchings.” The young gay artist celebrated this feeling of freedom by following the advice of a Clairol advertising campaign, “Is It True Blondes Have More Fun?” and turning his hair into what would become his defining look.

It was in New York that Hockney started the suite of etchings that established him as a young artist to watch. The series is a reworking of the classic eighteenth-century saga of debauchery by William Hogarth called “The Rake’s Progress.” He sold the plates for £5,000 in London and headed right back to New York. Hockney had always had a vision of California, though, and he shows me an image that he made in 1963, “Domestic Scene, Los Angeles”, which depicts two men joyously showering. “That was before I’d been there. It was taken from a copy of Physique Pictorial magazine,” he says. He made it to the West Coast the following year. “I remember flying in and looking down at the swimming pools and thinking, ‘Now this is going to be OK,’” he says. Was LA anything like his Domestic Scene image? “It turned out to be similar.”

City of Night, John Rechy’s classic novel about a young hustler, partially set in Pershing Square, a park in downtown LA, had been a big part of Hockney’s California vision. So on the morning of his second day in the city, he bought a bicycle and cycled down there. “I found no one in it. It was deserted. So I cycled all the way back,” he says. Hockney was deflated. But it showed him that he had to learn how to drive. “Within a week of arriving here I’d got a driving license, I’d bought a car, and I’d found a studio,” he says. “And I thought, ‘This is the place to be.’”

“I’m not one for looking at the past that much,” Hockney says. “I’m always concerned with the now. I live in the now.”

David Hockney’s long career — he will be eighty next year — has been multidirectional, which separates him from the many artists, such as aging rock stars, who simply recycle their greatest hits. It has taken him from painting portraits and landscapes to designing sets for New York’s Metropolitan Opera. But he has always been anchored in drawing, in figuration, which separates him further from our new salon, those mostly younger artists trotting out chic abstraction. He is well aware of this. “I thought the Frank Stella exhibition was perhaps about the end of abstraction,” he says of the art-world grandee’s recent solo show at New York’s Whitney Museum. “He certainly pulled it every way possible, didn’t he? I mean, if you really think about it, abstraction can’t go on that long,” he says. “When people say you can’t paint landscape now, that’s like saying the landscape is so boring. Well, it isn’t the landscape that’s boring, it’s just our depictions of it. It’s the same with portraits.”

Does David Hockney feel that the real world he so loves to paint is the same as the one we both grew up in? Isn’t nature on the run somewhat? Those California lawns he loves are browning, there’s water rationing for those swimming pools, right? “Well, I think that’s short term,” Hockney says. “I don’t think we are going to run out of water. How can we? It may be salty, but we can have desalination plants. I know what you mean about things getting mad. But I always notice that life goes on. We are completely adaptable to anything.”

What has been totally individual about Hockney’s career is the way that his traditional painterly skills are paralleled by his intense interest in the technology of picture-making, a field in which he can be almost perversely cutting-edge. He developed a technique of sending works on paper through a fax machine to alter their appearance. Hockney used the process to great effect during a late ’80s hurricane that lashed the Southern California coast.

“I’m having breakfast in Malibu,” he says. “And a wave came right to the window. It was rather a fierce thing. And I made a fax of it and sent it out. A 144-page fax. I’ve always been interested in any technology that you can use to make pictures. So the moment I heard that you could draw on an iPad, I got one.”

Hockney loves photography but says it can never equal painting because it cannot capture time. Or not often. He makes exceptions for Guy Bourdin and Henri Cartier-Bresson. “Guy Bourdin was very good. I met him once and he said to me that if he could draw he wouldn’t have used photography,” Hockney says. “Cartier-Bresson, if you just say the name, six images come into your head, don’t they? They are amazing images — memorable. Most photographs aren’t memorable. What makes a memorable picture? If there was a formula, there’d be a lot more, wouldn’t there.”

There has been much scuttlebutt in the New York art world recently about “unskilled” and “semi-skilled” artists, meaning practitioners who have picked up their chops from Photoshop. In a world of holograms and computer programs, is it still really necessary to have the skills that Hockney developed over hours of figure drawing at school?

“Well, it’s necessary to draw,” he says. “Even the computer doesn’t stop you from drawing, does it? No! It’s always back to the drawing board. People in New York, they must be making excuses for feebleness.” Next year, he and the writer Martin Gayford will be bringing out a history of picture-making — all pictures, including photography and the movies. It’s these two mediums that have lured David Hockney to one of his most remarkable obsessions — perspective.

“It isn’t the landscape that’s boring, it’s just our depictions of it,” Hockney says.

Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters, a book he published in 2001, which was based on studies he made with the physicist Charles M. Falco, argues that European artists used optical devices, including mirrors, to bring three-dimensional perspective into their work. It is well known that the Italian artist and architect Filippo Brunelleschi, who created a 3-D drawing of the Florence Baptistery in 1420, made a breakthrough. Hockney is convinced that he completed the drawing by projecting the image onto a panel with a concave mirror, and he made his own test to confirm this in September 2000. “That is how perspective was born. I’m sure that’s how it happened,” he says.

Like Hockney, Brunelleschi had needed shadows for his work. “Optics needed shadows, like photography needed shadows,” Hockney says. “Shadows have never been looked at. No art historian talks about shadows.”

The Hockney theory has been both defended and savagely attacked by academics. I am unqualified to say anything, except that it’s kind of thrilling. These are the same thrills communicated by Hockney’s iPad works, and his Neo-Cubist videos, such as the upcoming one he is making for the Royal Academy show and the nine-camera trip through the Yorkshire woods that dominated his last show at Pace Gallery in Chelsea, New York. All of this answers my first unformed question. David Hockney has floated above his peers for much the same reason that Andy Warhol has, which is that the issues he plays with continue to be of intense interest, not least of all to younger artists.