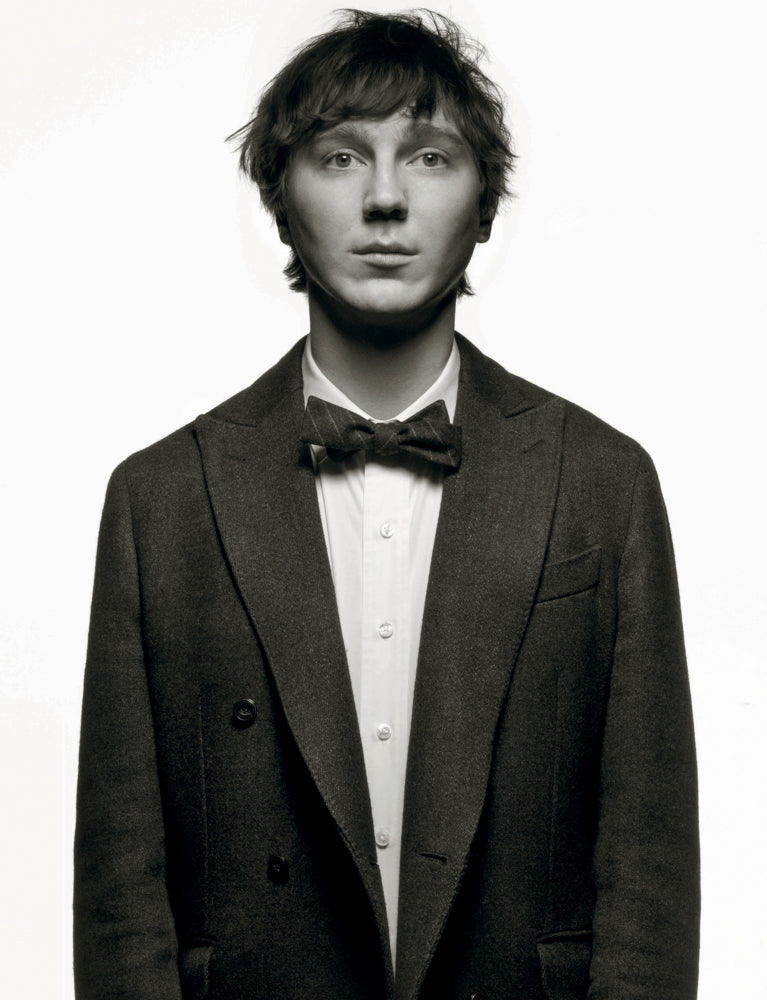

Walter Robinson

WALTER ROBINSON

The artist and writer gives his first love a second chance

Walter Robinson arrived in New York in the late 1960s, around the same time as Larry Clark and David Salle, to name a couple fellow Okies — neither of whom he knew — who had migrated from the Great Plains to the Big Smoke. Declining to turn on, tune in, and drop out like so many of his fellow students, Robinson completed his critical studies at Columbia, and began his epic pilgrimage through the New York art world.

By 1973, he was living in the frugal splendor of an unconverted SoHo loft on Wooster Street, just around the corner from where the Wolford lingerie store stands today. Along with fellow grads Edit deAk and Joshua Cohn, he launched Art-Rite, a proto-’zine printed on the cheapest newsprint money could buy, and distributed it free in downtown galleries. The magazine promised to “bring into your home the romance of the underculture — horse racing, white-trash smut, greasy rock and roll, muscles, motorcycles and the end of civilization.” The few extant copies of that excellent youthful caprice now command high prices among collectors of art-related ephemera.

In 1979 Robinson joined Collaborative Projects, a gang of starving but fashionable artists that included Eric Mitchell, Robin Winters, Jane Dickson, Jenny Holzer, Tom Otterness, the Fabulous Ahearn Twins, and Kiki Smith, among other talents. Collab was looking for government grant money by any means necessary, and the most successful of their endeavors was an exhibition, The Times Square Show, the details of which have passed into legend, and become fodder for many a postgraduate thesis.

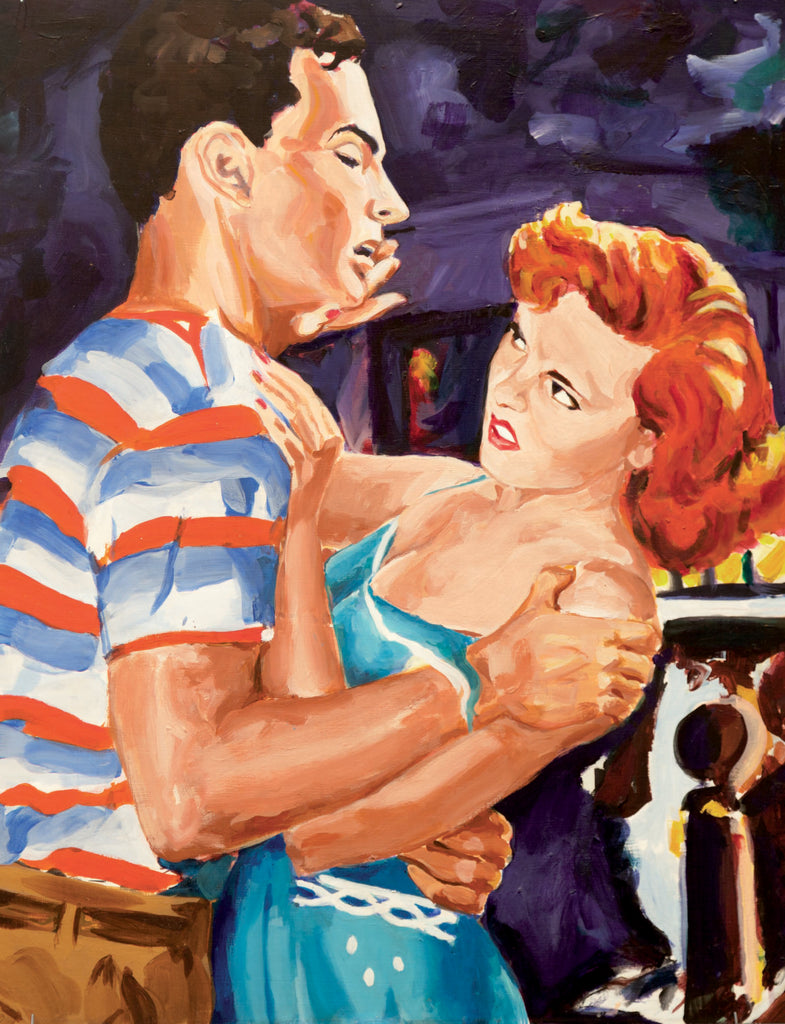

Robinson’s art practice bloomed in this romantic and penurious climate. Inspired by pulp comics, he began painting lurid scenes of tough guys and tougher dames, often on the verge of carnal embrace. Helene Winer and her brand-new gallery, Metro Pictures, picked him up, and his first show there met with critical acclaim and some monetary success. Subsequent shows at the gallery included, in 1985, a series of spin paintings made with sign painters’ enamel on square canvases, which not only predated Damien Hirst by at least a decade but also far outstripped him in technical proficiency and simple beauty. That year they failed to find a single buyer, but recently collectors have begun to gather like moths around these flaming, self-propelled works.

Robinson, careless of ‘brand identity,’ then switched to the depiction of various pharmaceuticals and over-the-counter drugstore items, including a bottle of baby oil (which was bought by a member of the Johnson & Johnson family), an oddly sensual box of Tampax, coyly turned away from the viewer’s gaze, and a brushy bottle of Bromo Seltzer, which the artist says was a sly reference to the fact that the raging angst of the Abstract Expressionists “might have been a sort of indigestion.”

In 1988 Robinson broke off his painting practice to raise his daughter and refocused in earnest on his art-writing career. He eventually became founding editor of Artnet Magazine, where he monitored and frequently castigated the mercurial fluctuations of the art scene for sixteen years. In 2008 Metro’s Helene Winer coaxed Robinson into taking a group of his pulp paintings out of storage and gave him a show in her now prestigious gallery in Chelsea. The art world had by this time begun to take note of these voluptuous, lushly painted works, and brisk sales put enough money in the artist’s pocket for him to resume a full time painting practice.

On a recent visit to his Long Island City studio there were still plenty of curvaceous nudes in evidence, but also some terrific examples of what Robinson describes as his “norm-core” paintings, images taken from mail order catalogs like Lands’ End and Target. A painting of a woman in a lilac dressing gown epitomizes Robinson’s ability to translate the ordinary into the sublime; to inject a subtle, surreptitious eroticism into a rather banal image. “Edmund Burke defined the sublime as ‘dangerous things seen from a safe distance,’ ” says Robinson, looking up from Wikipedia, “and that neck-to-ankle flannel nightie is nothing if not scary.” For this viewer, groomed as a youth by the ladies underwear section of mail order catalogs, it’s also very alluring, and so are the suburban girls romping on the beach in stripes and polka dots, unaware they might be channeling Barnett Newman and Yayoi Kusama.

“My art is always about desire,” he says, “especially at the beginning. Making a painting is sensuous and cerebral, dreamy and focused, intent and uncertain. When I was much younger I painted pictures of people kissing, and realized that these works had an ancillary effect — they piqued the interest of some very attractive women. I got dates!”