All Too Real

ALL TOO REAL

THE DYSTOPIAN WORLDS OF FREEMAN AND LOWE

It’s easy to miss the entrance at Red Bull Studios in Manhattan, where the doors have been blacked over and the signage removed for Jonah Freeman and Justin Lowe’s installation Scenario in the Shade.

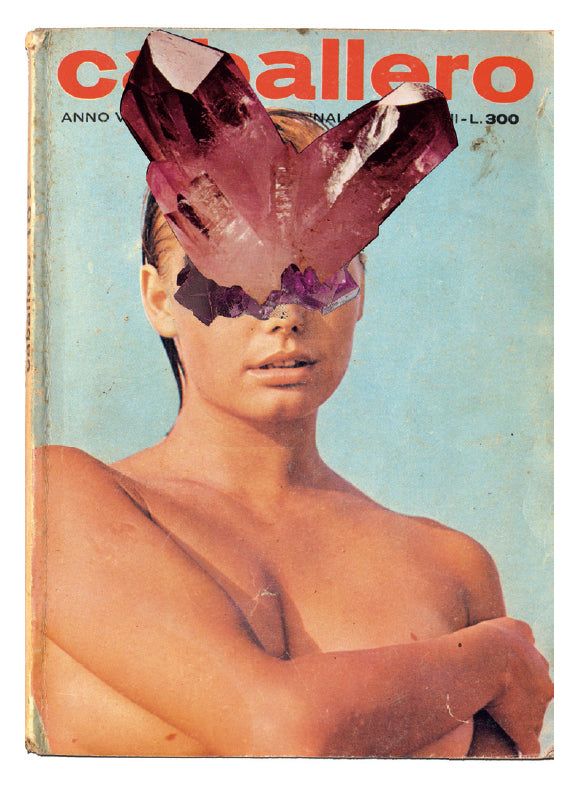

Inside, the artwork is on two floors, in room after room, each suggesting a different story — jars on shelves in one, caps hung on pegs in another, elsewhere the soft-core erotica of Venice Beach towels, a slathering of collages, clippings, photographs, tapes, and invented books. Moving around, viewers slip through a sonic envelope put together by Freeman and Lowe’s partner on this project, Jennifer Herrema, who wrangled contributions from performers including Bad Brains and Bobby Gillespie of Primal Scream.

There are no actors in this installation. Any human presence is implied by the materials, which mostly reference the youth cultures of 1970s California. Freeman and Lowe have given their scenes a fictive origin, San San, a megalopolis that stretches from San Francisco to Santa Barbara. The city’s history is reinforced by a twenty-eight-minute movie playing on a loop in the last space on the ground floor. Like their earlier object-generated narratives, Scenario in the Shade is both a trip and a formal development in the making of art.

Jonah Freeman was born in Santa Fe, New Mexico, in 1975, and Justin Lowe a year later in Dayton, Ohio. They met when they lived in the same building in Los Angeles. “Then our studios were across the hall from each other when we moved to Williamsburg [Brooklyn],” says Lowe. “We both ended up living in the building. We spent a lot of time talking about ideas, and we started making collages together.”

The two became preoccupied by the subcultures they had witnessed growing up in the ’80s, as well as the sources that had nourished them during that time, including sci-fi movies, Cold War culture, and the works of William Burroughs, Ray Bradbury, and Philip K. Dick. “The films we were seeing, the books we were reading, were ruminations on that,” says Freeman. That was the germ of their first collaboration, Hello Meth Lab in the Sun, which was commissioned by Ballroom Marfa in West Texas and opened in September 2008.

Meth Lab was a huge network of installations, including elements of a hippie commune, a burnt-out flophouse, a fully equipped meth lab, and a loft, collaged with images from Fangoria magazine. The timing didn’t hurt. “It became a sensational subject, partly because Breaking Bad was bringing that culture into popular focus,” says Freeman.

“Our project was approved. And then a few weeks after, the show came out. The first episode premiered as we were building the piece.” Their show got enormous attention and a follow-up, Hello Meth Lab With a View, was one of the hits of Art Basel Miami Beach that December.

Next came Black Acid Co-op for Deitch Projects in New York in 2009. Back then, Freeman and Lowe had also been making their own work individually, but since 2010 they have focused on collaborations. “Because our projects are so large in scale, and take up so much time,” says Lowe.

Acid! Meth! When I meet the artists inside their installation I observe that I had once asked Tom Wolfe how far he had gone in his research for The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. Not that far, he intimated. What about Freeman and Lowe? “I think we both did enough of it in our younger years,” says Lowe. “Yes. It’s been kind of a longer journey getting away from it than getting into it, I think,” agrees Freeman.

A casual reader of their critiques, I noted, would think that’s their main subject. “Yeah. It has a way of coming to the forefront for sure,” says Lowe. How do they arrive at a new project? “Well, we have to go and see the space if it’s a site-specific installation. From there it’s pretty nuts and bolts, what we can and cannot do. Like, you cannot drill under the floor — fire code issues.

A lot of it is picking how the rooms would go together. And we always try to take in the neighborhood where we’re doing the installation, so that when you enter the space there is a sort of slow fade into what will become a completely other place.”

What about the stuff they put together? Do they stockpile, or seek out material for a specific project? “Well, it’s a little of both,” says Freeman. “We do have a vast image archive and video archive, and reference materials, things like that. And we have it organized in such a way that when there comes a point that you need something, we have it there at our fingertips.”

I note that they and Damien Hirst have the best titles in the art world, such as Bright White Underground and The Artichoke Underground, a wholly fictive print shop, created by an equally fictive collective, which Freeman and Lowe installed in the Marlborough Chelsea space at Art Basel’s Unlimited section in Switzerland in 2013.

How do they come up with them? “Oh, God. I don’t know. Sometimes it’s just...drinking too much,” jokes Free-man. “It can take us a long time to come up with them. We have an ongoing list that is now, I think, a thousand titles long,” says Lowe. “In the last show at Marlborough we actually printed out the entire list and put it on the wall,” adds Freeman.

Before the duo created their own made-up version, the megacity SanSan had been predicted by the futurists Herman Kahn and Anthony J. Wiener in The Year 2000: A Framework for Speculation on the Next Thirty-Three Years, which came out in 1967, right before the Summer of Love, and was a flop as prophecy — at least in timing. What would Freeman and Lowe’s San San be like?

“San San has a severe class division,” says Freeman. “It’s mostly a privatized world. The government has been emasculated. If you are the upper middle class or the upper class, you are protected by private security and your money controls a lot of things. And if you are in the underclass or the lower class your government and security is usually a gang or a mafia. Which is not so different perhaps from the way things were at the beginning of the twentieth century.”

Or from the current state of affairs, I say. “Yes. Exactly!” says Freeman. Do they have an idea of what their next project will be? “We want to keep making films,” says Freeman. “Because we’ve done a lot of these installations. Although some have been purchased and will be preserved, a lot have not. So film is a way to take the ideas and the environments and have them encapsulated intact. And we have developed this whole fictional universe of the San San International, which allows for a very expansive process in which you can take any number of different subjects and twist them into the world of this megacity.”

Does San San have a future? “I think that there will be a continuation. The film ends in a way that alludes to a new chapter. It says that we are in a new place now — Mercury City. But since our next project is in Mexico, maybe that’s where San San might spread. Jennifer Herrema says it goes all the way to Alaska.”