Aaron Young

AARON YOUNG

Artist Aaron Young and Andy Warhol Museum director Eric Shiner, who met as grad students at Yale, discuss getting older, gang handshakes, and navigating the globalized art world.

ERIC SHINER: Can you believe we’ve known each other for ten years? When we met I was editing Palimpsest [the Yale graduate student literary and arts magazine]. I published your photograph of the Yale soccer team spitting blue Gatorade into the air, creating a geodesic dome à la Buckminster Fuller. I saw that work a few weeks ago in Alabama at the Birmingham Museum of Art. It was a new acquisition.

AARON YOUNG: I sold that piece to the collector who gave it to the museum very early on, before I first showed it in 2005 at MoMA PS1’s exhibition “Greater New York.”

ES: It was like old home week seeing it there. I also remember in school you made an amazing work with members of the New Haven Police Department throwing gang signs in front of an old garage. How did you get them to do that?

AY: It’s about letting people know what you want them to do but, if they’re not going to agree to it, shaping it in a different way so they will. It was kind of lying to the police.

"I think we were pretty lucky because at that point the New York art world was really hungry for fresh ideas."

ES: After grad school we both made our way to New York. While I was curating shows, you were doing great projects. I remember your bronze rock sculpture, “LOCALS ONLY! (Bayonne, New Jersey),” in the 2006 Whitney Biennale; then in 2007, “Greeting Card,” your motorcycle performance piece at the Seventh Regiment Armory. How was the whole New York thing for you?

AY: I think we were pretty lucky because at that point the New York art world was really hungry for fresh ideas. I don’t think people are getting the same chances now that we were then.

ES: True, it was a different universe: The market was high, people were willing to take risks, and we were able to ride that wave. Now the market has contracted, young curators don’t have as many opportunities in physical space—although they’re doing interesting things in cyberspace, putting together online exhibitions, thinking about art and how it’s displayed in new ways. But back to New York: Neither one of us really lives there anymore; I’m in Pittsburgh and you’re in, where, Miami?

AY: Well, I am based in New York again now, but my fiancée, Laure Heriard Dubreuil, is from Paris so we’re there quite a bit; she also has a store called The Webster in Miami, where we are right now. Basically my practice has become post-studio; I had one for about two years but now I work everywhere I go, which really frees me up. I get to experience so many different places and work with so many different people.

ES: We’re both very nomadic now, crisscrossing the globe. The Warhol has a large traveling exhibition in Asia right now, so I’m spending a lot of time there.

AY: I spend most of my time in Europe. I was just in Istanbul for the first time, speaking on a panel called Istancool, part of the Istanbul International Arts and Culture Festival, and now I have a gallery there, where I’m going to do a show next March. Before Istanbul, I was in Lebanon. The Aïshti Foundation is a new museum being built on the Beirut waterfront; I’m going to do the inaugural show and performance there in 2013.

ES: That’s fantastic!

AY: I guess New York is the center of the art world, but it’s really nice to get outside of it. All kinds of pressures drop away; people are more interested in ideas about your work rather than how much it costs.

ES: I agree. It’s great to spend a couple of days each month in New York, see what’s going on, be refreshed, meet friends, and then go on to the next place and see what’s happening there.

AY: Traveling to a new city, you know you’re there for a limited amount of time, so you pack in as much as you possibly can, seeing as many shows, and hanging out with as many people as possible. It’s exhilarating.

ES: Completely agree! So tell me about the new project you’re working on with car bumpers.

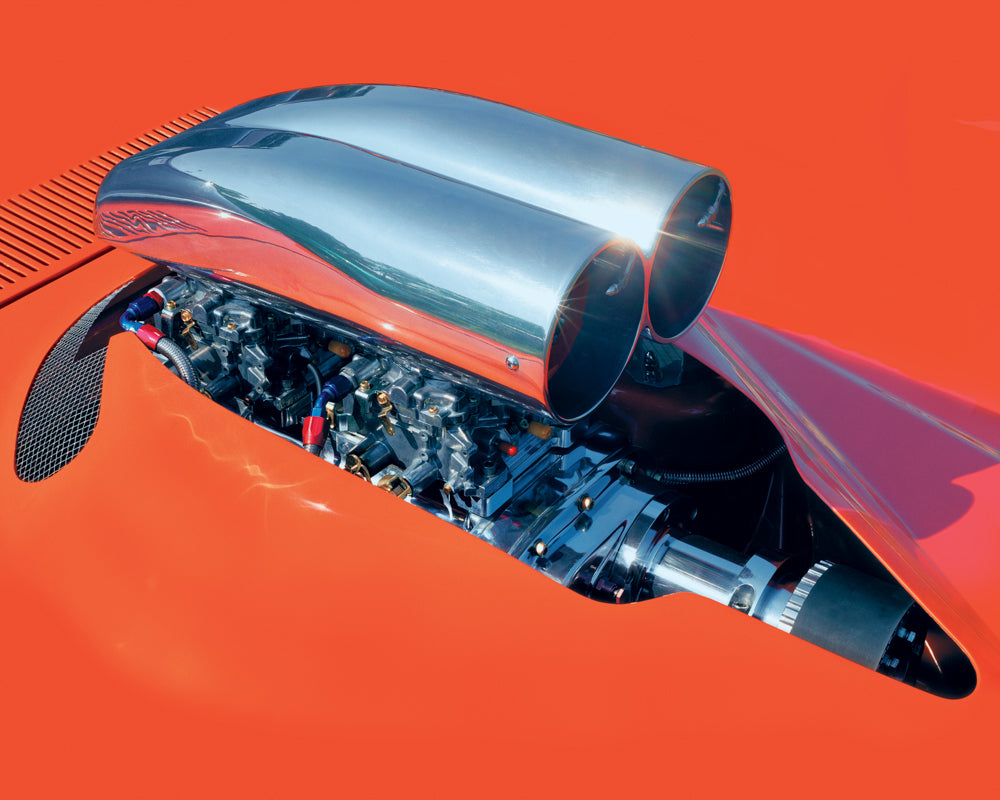

AY: Not bumpers, but spoilers from American muscle cars. I was never really into cars, motorcycles, sports, or anything overtly macho like that. But I was interested in looking at those things outside their intended function. The spoilers have a macho aspect to them; they’re phallic in a way. But along with those attributes, there’s also an art dimension, with strong references to minimalism—especially in the way that I’m presenting them — with a relationship to the work of Donald Judd and John McCraken. I like mixing the macho and the minimalist together. The spoilers all come from cars made during a boom economy for the U.S. automotive industry. I think it’s a really good time to crash together the worlds of what we once had, American muscle thinking, and where we are today. Looking at minimalism is always a good way to start in sculpture.

ES: Absolutely. Knowing that cars, motorcycles, and sports were never a direct interest, it’s amazing what you’ve done with those very specific American phenomena. I’m thinking of you dropping a car into a frozen lake; making a video of girls in bikinis washing a sports car, viewed from the inside; obviously, the motorcycle performances; and now the spoiler sculptures. I love how you’ve used metallic auto paint to make them candy-colored gorgeous, and then hung them pristinely as though they were Donald Judd sculptures. They also made me think about John Chamberlain and his sculptures using car parts, so you’re linking to that, too.

AY: I was looking at some Chamberlains the other day and thinking about other sculptures I’d made — 24-karat gold-plated crushed chain-link fences and cast-bronze police barricades — which are completely relatable to Chamberlain as well.

ES: Yes, especially in terms of how you’re playing with materiality. Those police barricades are a prime example: They look like painted wood but they’re made of bronze. They’re absolutely stunning. I put them in my first show at The Warhol, “The End: Analyzing Art in Troubled Times,” back in 2009.

AY: One reviewer called them really lazy. He said that Young just went out on the street, picked up a bunch of police lines, and stacked them in the gallery.

ES: Clearly he didn’t read any information about your work.

AY: Sometimes reviewers get lazy themselves.

ES: So right back at you reviewer! (Laughter.) Besides the spoilers, what else are you working on right now?

AY: I have a show coming up at Kukje Gallery in Seoul, for which I’ve just finished a bunch of paintings depicting handshakes I’ve sourced from American, Asian, Russian, and West and East European gangs. Some of them have up to 60 components, which I’ve broken down step by step. The paintings have to do with value — what used to be thought common value and what is thought common value today. Now that artists and curators work in so many different countries, they have to think about, not being site specific, exactly, but about being relatable. There are only a few things that I show in New York that I would show in Korea. Can you relate to that?

"I like mixing the macho and the minimalist."

ES: Absolutely. Having lived in Asia for six years, I know that making specific cultural references helps the audience engage with a piece, which they might have difficulty doing if it’s coming from a completely different place.

AY: I just showed some paintings in Los Angeles that were quite site specific — images of celebrities like Casey Anthony and Lindsay Lohan that nobody’s going to give a shit about over in Asia.

ES: Warhol was successful because he was basically universal, using democratic images like Marilyn Monroe, who is a global phenomenon. But the idea of referencing the local condition is an interesting one for artists to consider; it doesn’t happen as often as you would think. I’ve worked on many exhibitions where I’ve invited artists into a particular city or country and asked them to spend time and make a new work based on whatever experience they might happen to have there.

AY: That relates to what we were talking about — trying to pack as much as you can into a visit gathering up material, and then filtering it into a work.

ES: Much of what you’ve done makes a direct and oftentimes critical comment on American culture from one perspective or another. Would you agree?

AY: For sure. And there are things that have sprung out of my time in different countries. For instance, in 2010 I made a big site-specific sculpture in front of the Teatro di Marcello in Rome. It was a large gold carriage impaled on a Doric column. It was definitely filtered through me but I took all the material and history from the place. Because I am American, they had a bit of difficulty with it at first; I think if an Italian artist had done it, it would have been different.

ES: Maybe people think initially that as an outsider, you’re critiquing their culture directly. Whereas you have just as much authorship over that material as anyone, insofaras Roman mythology and history are a basic part of most Americans’ early education, too.

AY: Yes, it’s that interesting position we’ve been talking about, where we are more citizens of the world and not just relatable through our passports.